Unforeseen events dominate the course of our lives, but also that of the practices of science, its collections, and that of collectors of facts, objects, and experiences.

Thousands of stories confirm it.

Among them is a story that begins with the accident of an airship in the Barents Sea and ends in the fall of 1985 with the death of the Norwegian engineer Asbjorn Pedersen in the Autonomous City of Buenos Aires, the former Federal Capital.

A few months before that fall, the Argentine anthropologist Julián Cáceres Freyre had accepted his invitation to visit him at his home at 1480 Paraguay Street. He had been left a widower, he was alone, in poor health, with financial constraints, and wanted advice on what to do with a part of his archaeological collection, in particular with a mummy, obtained as payment for an installation made in the 1940s in a neighboring house or, at least, nearby.

At that time -in the 1940s-, Pedersen managed the company "Gas service" and traveled through his adopted country at the same time that he developed his love of studying the pre-Hispanic American past that, until his arrival in Buenos Aires, was completely oblivious to him.

He had arrived in the country in 1928, with his still brand new title, to help the team of the famous polar explorer Roald Amundsen (1872-1928) who was preparing their next airship trip to Antarctica. Amundsen, the fourth son of a family of Norwegian shipowners and ship captains, had been one of the first to reach the South Pole, an event that occurred in December 1911, the year of Florentino Ameghino's death, that is, 110 years ago. Their expeditions, marked by competition with other teams of equal pretensions, flooded the international press and also Argentina, creating a sort of "heroic age of Antarctic exploration", which explains, in part, the fervor for the southern ice that appears, for example, in the "Elogio de Ameghino", the work of Leopoldo Lugones published in 1915.

Amundsen, precisely in those years, would leave the exploration by ship to begin to experiment with the means of transport that the Great War made available to entrepreneurs and intrepid: air navigation that, as that word and its relative "airport" indicate, still in our days keep their seafaring ancestry.

The first attempt to fly over the North Pole dates from 1923. He failed. Amundsen and his companion from the Royal Norwegian Navy intended to reach Spitsbergen from Wainwright, Alaska, via the North Pole. The plane, however, did not respond.

Roald Amundsen dressed in furs, circa 1923.

In 1925, Amundsen, the pilot, the flight mechanic, two other members of the team, and the American Lincoln Ellsworth (1880-1951), the son of a coal magnate who financed the trip with $ 100,000, turned to the N-24s and N-25, two Dornier Do J seaplanes –called “whale”- with which they reached 87 ° 44 ′ north. It was the northernmost latitude up to that time visited by an aircraft, a milestone achieved thanks to the workshops of the German engineer Claudius Dornier, famous for these aircraft, equipped with Rolls-Royce Eagle engines manufactured in Manchester (England) and built in metal by the Italian firm Costruzione Meccaniche Aeronautiche Società Anonima (CMASA) as a result of the restrictions imposed by the Versailles treaty that prevented its assembly in Germany. These air whales were a great commercial success, fueled, among other things, by the voyages of Amundsen's team. These, just two years after the flight of the first prototype, managed to return triumphant when everyone thought they had been lost and Ellsworth father died in Italy waiting for news of his son. Lincoln E. never consoled him and, until his death in 1951, he would continue with his life as an explorer from both poles and as a benefactor of the American Museum of Natural History in New York, where a room exhibits the history of the travels of he. Antarctica, for its part, bears the name of Ellsworth engraved in various parts of its territory.

In 1926, the team would test the technology of the semi-rigid airships also built in Italy, where between the two world wars this industry developed greatly. There, the state factory Stabilimento di Costruzioni Aeronautiche (SCA) under the direction of the general and aeronautical engineer Umberto Nobile (1885-1978), built, among others, the Norge, the Italia and the W6 OSOAVIAKhIM for the Union airship program Soviet. With the Norge, Amundsen, Ellsworth and the Italian crew they made the first air crossing of the Arctic: they left Spitsbergen (today Svalbard) on May 11, 1926, flew over the Pole on May 12 and landed in Alaska the next day.

In 1928, while Amundsen planned a similar expedition in Antarctica and the young Asbjorn Pedersen left for Buenos Aires, Nobile embarked on Italy to explore unknown regions of the Arctic. In May 1928, on the third flight, the aircraft crashed on the ice north of Spitsbergen. Although Nobile and 7 companions were rescued, 17 lives were lost: the Italian investigation declared Nobile responsible for the disaster and he resigned from his position. In 1931, he would participate in a Soviet trip to the Arctic and it would be necessary to wait for the end of World War II to annul the record of 1928: thanks to this, Nobile was reinstated in the air force, he resumed teaching in Naples and was a deputy in the Italian Constituent Assembly of 1946. Amundsen, on the other hand, never returned to Antarctica: while trying to find Nobile and his men, he disappeared on June 18, 1928. Apparently, the French seaplane Latham 47 crashed in the Barents Sea. A wing and a gas tank of the plane were found near the coast of Tromsø but the Norwegian government suspended the search in September. The bodies remain missing.

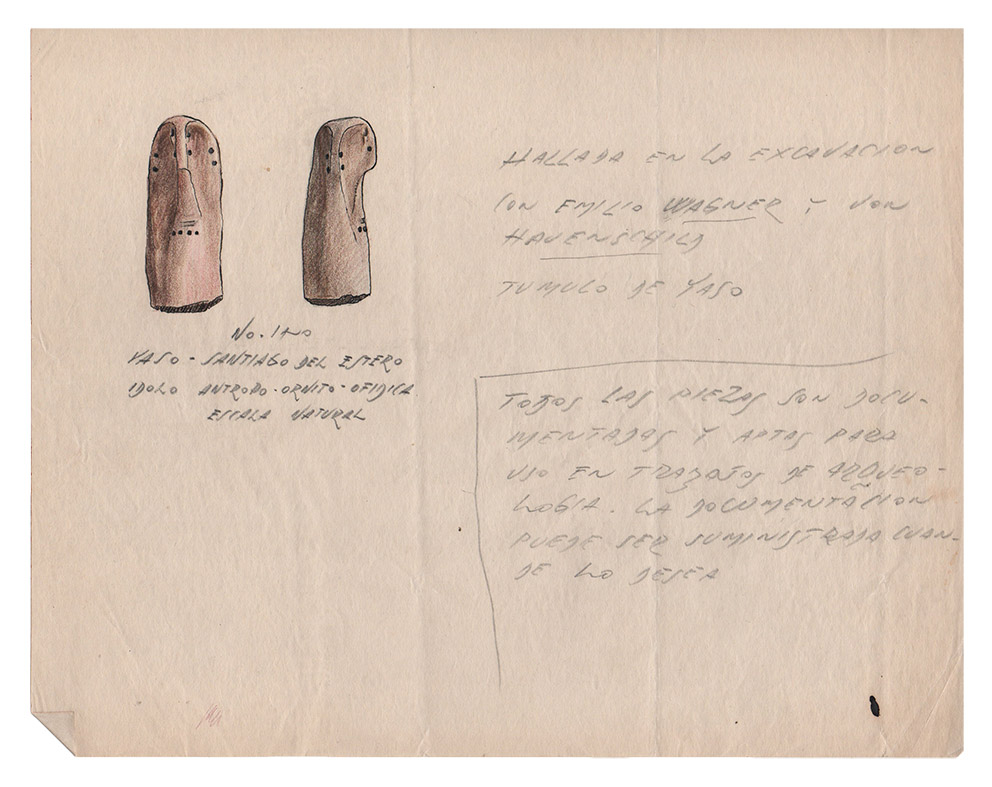

Pedersen, we do not know how or why, he stayed in Buenos Aires, where he changed his polar destiny for another marked by the automobile, the mountain landscapes and the crossing of Córdoba and Santiago del Estero. He became an Argentine citizen in the 1930s and married Chela Gómez Clara whom he met at a service station in Córdoba, where he worked as an engineer. At that stop, he met the car of a woman from the area who was traveling accompanied by her daughter, a young woman with whom he fell in love. A few days later, he went to the family home and asked for her hand. Chela was, in addition to being pretty, a sculptor and daughter of the Cordovan artist Emiliano Gómez Clara (1880-1931), who had studied in Europe thanks to a grant from the Government of his province. Chela exhibited his work at the XIV Autumn Salon of the city of Rosario, held in May 1935. Interested in art, heirs to Emiliano's work, the Pedersen-Gómez Clara family invested part of their time in the study of the cave paintings of the Sierras de Córdoba. Pedersen worked in the irrigation canals of the Río Negro and in the large hydroelectric works, dedicating a large part of his income to the study of archeology, making trips to Peru, where he acquired numerous pieces for his collection. In addition to promoting the use of infrared rays in the analysis of the paintings of Cerro Colorado, in the north of the Province, Pedersen, throughout his devotion to the subject, discovered some 200 caves and shelters and reproduced more than 30 thousand drawings in colors using the technique that he proposed. In this regard, he published several works in Argentina and some notes in The New York Times. Partly thanks to his efforts and his travels, Cerro Colorado was declared an Archaeological and Natural Park in 1957.

Cave painting from Cerro Colorado, Córdoba Province, Argentina.

Not only that: Pedersen between 1945 and 1946 donated to the United States National Museum (Washington, DC) a 206 g sample of the Malotas meteorite, an ordinary chondrite that fell in the shower of thousands of stones on June 22, 1913 at 4:30 hours in an area of 5 x 2.5 km in the department of Salavina, Province of Santiago del Estero.

Pedersen would elaborate his own theories about the origin of the horse represented in the paintings he studied as well as the relationships between them, at a time in the history of anthropological disciplines where collectors, amateurs and professionals met at the meetings of the Argentine Society of Anthropology, in the congresses dedicated to rock art and the past of aboriginal societies. He was a regular contributor to the National Institute of Anthropology and to Julián Cáceres Freyre, its director. His survey work was cited by all those interested in the country's rock art: thus, among others, the American anthropologist, sister (Benedictine) Marie Inez Hilger and her companion Margaret Mondloch in "Rock paintings in Argentina" published in the magazine Anthropos In 1962, they refer to the work of the Norwegian engineer who, let us emphasize once again, financed his research with his salaries and the money obtained from the payment of his clients.

One of them turned out to be the widow of Perfecto Paciente Bustamante, a Riojan herbalist based in Buenos Aires and owner of a natural history house-museum. There, on Avenida Pueyrredón, Bustamante sold Andean weeds and exhibited a collection that included embalmed animals, fossils, antiques and a "mummy" found in the Andes, which since 1932, after the death of Perfecto Paciente, remained in the storage room of home. The widow traded it to Pedersen for the installation of a kitchen, a refrigerator and a water heater which, thanks to this transaction, became "exchange material": the mummy was integrated into the collection of a fan of the art of the past and household appliances added comfort to the home of someone who, in life, had been a cultist of anti-modernity.

A widower, alone, ill, in 1985, he tried with Cáceres Freyres the possibility of offering Bustamante's mummy to the National Museum of Man, established in 1981 at the National Institute of Anthropology, with which Pedersen had collaborated for more than 30 years. Given the need for money and the lack of national funds, it was decided to send it to the Casa Posadas in Buenos Aires, where it was finished on August 9, 1985 and where it would never have arrived if Italy, in 1928, had not crashed in the Arctic and without Mr. Perfect Patient would have left his wife with a house adapted to the domestic life of the twentieth century.