This story begins in a warehouse of the FAMILLE Association, SOLIDARITÉ ET CULTURES located on the Boulevard de la Liberación in the city of Marseille. Or a little earlier, it is true, on a morning of torrential rain, impossible for a walk without a raincoat or protection of any kind, on a pause on that excursion that went in the direction of the Natural History Museum of the city. A journey -it was not known yet- marked by the administration of water.

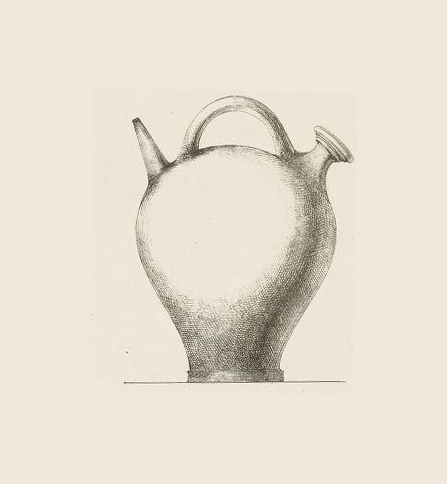

The Natural History Museum is located in the north wing of the magnificent Longchamps Palace, the twin wing of the one where, opposite, is the Museum of Fine Arts. It is a mansion that was inaugurated in 1869 to celebrate the end of the problems derived from the drought that devastated this Provençal port. Thanks to an engineering work that made it possible to transport the water from the Durance River to the homes of the people of Marseille, after more than 30 years of work, a complex network made up of 85 kilometers of channels and underground pipes managed to supply water to this city, where the sea reigns but drinking water is lacking. For this reason, to commemorate this milestone, it was decided to build the Longchamps Palace at the end of the avenue of the same name in the upper reaches of the Les Cinq Avenues neighborhood. It was commissioned by the architect Henri-Jacques Espérandieu (1829 - 1874) who designed it as a true ode to water, as reflected in the allegorical sculptures of fertility and abundance. This Baroque-inspired complex is made up of a majestic colonnade and a central fountain known as the Chateau d'eau or Water Castle. The fountain depicts a cart drawn by bulls that carries grapes and wheat and above it three female figures stand, a symbol of life, with falls and waterfalls whose noise made the rain of that day sound more terrible than it really was. Although by then, it did not matter much either: in Liberación, the solidarity association sold umbrellas for a couple of coins and, for the same price, a little further inside, you could get toys, clothes, antiques, books, pots and glassware. There were also many shelves full of ceramics, earthenware and porcelain of all kinds, colors and tastes, one of the many human perditions, a sign of sedentary life and a declared enemy of suitcases and air travel. Among the tidal wave of objects given to charity and awaiting their new owners, a jug stood out, a cylindrical vase, with a glazed finish, marbled in shades of creams and browns. Probably Provençal, apparently a bit old. With that vintage consisting of an umbrella and a jug under our arms, we returned to Cassis.

“What is this called in English?” -the English-speaking colleagues from the Camargo Foundation asked the next day. "Botijo"- answered the Wikipedia version in that language, confirming the Spanish origin of the object. (1) But, nevertheless, to the Francophones he said something else: “gargoulette”, a name that ratified, instead, its Mediterranean and Provençal stamp. The encyclopedia also called them cachucho, piporro, pirulo, peche and rallo, forgetting about “glass and ceramic”, a word that is now in disuse and invented in 1809 by Jean Fourmy, a potter from Paris. A word that is linked to the studies and experiments carried out in the early nineteenth century where the physics and chemistry of materials were combined with the large-scale production of earthenware and the possibility of mastering the technologies that guaranteed the cooling of liquids.

"YDROCÉRAME", Fourmy's neologism, was composed of two words of Greek origin: "Ydros" which referred to sweat, and keramos, to clay pots. This designated the family of glasses that sweated and any container of earth whose permeability enabled it to cool its contents thanks to the property of cooling by means of the transudation mechanism.

Glazed container with the handle and the two holes in the upper section; the mouth to carry and the python -smaller-, to drink. Photography: Adela Schäffner.

When the mineralogist and chemist Alexandre Brongniart (1770-1847) in 1844 published his Traité des arts céramiques ou Des poteries considérées dans leur histoire, leur pratique et leur théorie, he took up Fourmy's classification but added an H and an explanation reminiscent of the distribution of plants according to the climatic zones of the globe: a Hydrocerame was a type of ceramic that could be found in climates where the lowest temperature oscillated by an average of 15 degrees but also where it could rise well beyond 30. This type of glasses had the property of lowering the temperature of the liquids stored there to about 8 degrees with respect to the environment. The name given by Fourmy served, as in geology and mineralogy, to summarize in a single word all the regional names and, in this way, show that it was a technology shared by different regions dominated by the same problem. From India to Andalusia, passing through Egypt and the torrid area of the American continent, with details in the manufacture that marked its origin, all, however, shared one characteristic: they presented a large surface that favored rapid evaporation that cooled the water while avoiding to go to the gaseous state. The secret: the porosity of the paste, achieved by the addition of fine sand, fired ceramics, clay loams, low-temperature firing, the incorporation of substances later destroyed by firing. Among them, the salt that, when dissolved, left the paste full of small vesicles. The forms were as varied as the names used in the most distant geographies; singular in more than one case but always respecting the principle of extending the surface to achieve rapid evaporation of the water.

One of the first to break down the manufacture of these vessels had been the citizen Louis Lasteyrie who in 1797 published a memoir on the Spanish alcarrazas in the Journal des Mines, previously read in the French Philomatic Society. It was about those vessels that were manufactured in various regions of the neighboring country, mostly characterized by their grayish bank. Madrid supplied itself with them in Anduxar, Andalusia, a town that obtained the land to model them in the Tamasuro stream. According to Lasteyrie, it was a form imported by the Arabs and was still used in Egypt and other parts of Africa and Asia, the East Indies, Syria, Persia, China. On the other hand, they were unknown in Sicily and also in France. Lasteyre said:

"Despite the neighborhood and relations with Spain, no traveler has so far been in charge of spreading the procedures used in its manufacture of this element, the introduction of which would be extremely useful for our country, not only to cool off in hot weather but also for a health issue”.

As a result, Lasteyrie had been informed about the exact way used to make the alcazarras (2), he had also brought a few to exhibit them to his compatriots together with the samples of the land used, examples that Citizen Darcet analyzed chemically . As a result, it was found that the materials existed on French soil and that producing them would not be onerous.

Lasteyrie was not the only one to propose the import into France of the cooling methods used in other Mediterranean countries. The historian of science Patrice Bret, one of the scholars of Napoleon's expedition to Egypt (1798-1801), has shown that one of the technologies most observed by the French in that territory was precisely the one that allowed the locals to maintain fresh water in a climate as overwhelming as that of the African desert thanks to its storage in "bardaks" or "qollehs". In Egypt, the mathematician and geometer Louis Costaz (1767-1842) devoted himself to studying its thermal characteristics, which he later presented in Paris in a debate at the Society for the promotion of national industry created in 1801. For his part, Pierre Rouyer ( 1769-1831), the expedition's chief pharmacist, published a historical and chemical study of Egyptian ceramic arts highlighting "the advantages that the adoption of ceramics destined to cool water would bring for France." Shortly after, in 1802, a naturalist would once again exhibit a Spanish alcazarra and an Egyptian bardaca for analysis by Parisian scientists. It would be in this context that Fourmy would invent the name "ydroceramics" to bring together all known forms of refrigerant glasses, launching into the manufacture of them.

Brongniart, meanwhile, with an applied geologist's eye, dedicated himself to promoting the creation of the ceramic museum of the Sèvres porcelain factory by publishing his catalog in 1845 that included various shapes of sweating vessels from, in this case, Spain. Portugal and Egypt.

At the end of the 19th century the gargoulette was already part of the material culture of Provence, and although some claim it from local roots, this story that began on a rainy day seems to indicate that its spread coincides with the period of the great works of hydraulic engineering held by the Palais de Longchamps. Those that brought water to the houses of Marseille.

Notes:

1. Botijo: Porous clay pot used to hold water and drink from it. It has a handle at the top and has a mouth where it fills on one side and a drinking spout on the other side. The glazed jug, also called winter jug, is used today preferably as an object of decoration. (We have respected the words in italics as they were in the original) In Alfares y alfareros de España. By José Guerrero Martín. Ediciones del Serbal, Madrid, 1988, p. 279.

2. Alcazarra: Porous clay pot that, thanks to the evaporation of the water that seeps, cools the one that remains inside. José Guerrero Martín: ob. cit. 1988, p. 277.

* Written in Buenos Aires and in memory of the talks at the Camargo Foundation, in Cassis, France. Special for Hilario.