Moderately opulent cities -we said yesterday- discard the products of their history in the garbage can. There are plenty of examples in the form of a plate, cup or book that, if they are lucky, dodge or postpone fate by moving to another house, other owners, another function.

The vinyls, recently, managed to avoid it by the work and grace of a rebirth whose expiration date will arrive at any moment. Dictionaries and encyclopedias, it is announced on the horizon, are two species condemned to disappear. For some time now, they have been found on the sidewalks and in paper recovery warehouses. Compact discs, for their part, are begging through the streets and gather in the hallways with the Great Larousse Dictionary, the Meyers Konversations-Lexikon, books for teaching foreign languages, and baby clothes. A heap where Mozart's clarinet concertos coexist with words and pumps that nobody wears, music from movies that nobody sees, and stories read by some actor whose voice he believed to immortalize for that posterity that is not interested in them. Especially if they come from a country whose existence suddenly ceased. Like when, just yesterday, it happened on that night of November 9, 1989.

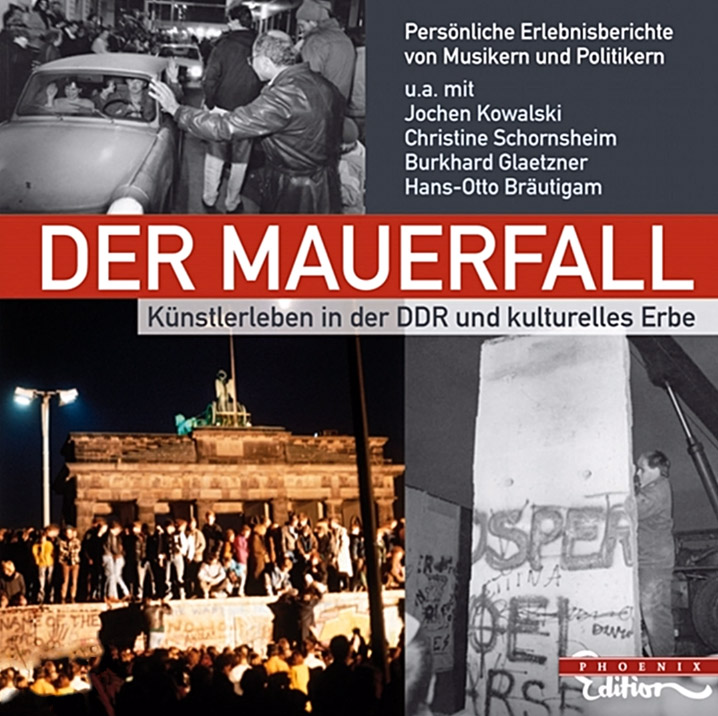

A historic night. Federal Germans mounted on the wall and ready to cross to the West. That cement barrier was almost 3.6 meters high, about 43 km long and had 302 watchtowers.

That day began the end of a country with a flag, currency, passport, Olympic medals, trophies and sports passion of all kinds. Parades, hymns, historical monuments, national and universal heroes. All useless when it comes to preventing, due to an error in the words used in a press conference by Günter Schabowski (1929-2015), a journalist from Neues Deutschland and a politician from the Politburo of the Berlin Socialist Unified Party, the announcement of the immediate freedom to travel through all border crossings from the German Democratic Republic to the Federal Republic and West Berlin. And with it, unintentionally, a border created and destroyed by history was dissolved.

Little more than 30 years have passed and practically nothing survives from that. Its citizens, whose homeland ended overnight, have been diluted into another that speaks the same language, but with other idioms and turns.

Children born in the 1980s today are in their forties raised in a world with abundance unknown to their grandparents and parents. Consumption at its best means that the shelves and walls are not enough and that the street must accommodate the remains of the country of their ancestors in order to continue accumulating what will be thrown away tomorrow.

So, someone, for some reason, one day broke away from “Der Mauerfall. Künstlerleben in der DDR und kulturelles Erbe”. Two compact discs, with the record of a series of interviews with singers, journalists and musicians invited to testify what life was like as an artist in the German Democratic Republic, the country where they had formed and developed their careers.

The album had been released in January 2010 as a commemoration of the 20th anniversary of the fall of the wall. It was an initiative promoted by the Phoenix record label, the profitable brother of Capriccio, a house founded in Vienna in 1982 and known for its catalog of music from all historical periods, on the condition that it was little known or recently rediscovered. After the bankruptcy of Delta Music GMBH, the artistic director of Capriccio, Johannes Kernmayer, decided to continue with several recording projects of the classical section of Delta known as "Phoenix Edition", a commercial gamble that allowed the rescue of the Capriccio catalog and reestablish the label as a new independent company. Capriccio today has to his credit operas by Hasse, Graun, Schreker and Zemlinsky; the symphonies of Joseph Martin Kraus, Gossec, Schulhoff and Ullmann; Kurt Weill's complete edition; film music by Shostakovich and Schnittke; and the series 'Portraits of the 20th century', with music by composers such as Ernst Bloch, Egon Wellesz and Paul Dessau. Among its artists are the harpsichordist and pianist Christine Schornsheim (1959-) and the countertenor Jochen Kowalski (1954-), two of the protagonists of “Life as an artist in the GDR” which is sold on Amazon and on other digital platforms where, new, it costs more than 20 euros and, used, a little more than half. Capriccio, in this world of the 21st century dominated by the concentration of publishing and record companies in a few hands, continues to be based in Vienna as a branch of the Naxos group.

The discarded album has no flaws, it is listened to without jumps, from A to Z. In the order that one pleases, the voices and opinions of those artists who today, in 2023, are retiring, have retired or deceased, but who, in 2009, were at the peak of their careers thanks to the recognition they had achieved in the Democratic Republic, in Europe and in the rest of the world without having to join the Communist Party. Kowalski and Schornsheim are joined by the baritone Olaf Bär (1957-) and the tenor Reiner Goldberg (1939-), the mezzo-soprano Uta Priew (1944-), the oboist and conductor Burkhard Glatzner (1943-), the violinist Conrad Muck, the actress Gisela May (1924-2016), the journalist Monika Zimmermann (1949-) and the politician and diplomat Hans Otto Bräutigam (1931-), talking about their experiences before and after the fall of the wall.

The interviews respond to questions that are intended to remind us of that extinct world where the rules were different, a reminiscence of the culture of that country where "music united people across existing borders." Among them, did culture help to break the wall between East and West? What cultural heritage did the German Democratic Republic leave behind? What walls fell? Which have been built since then? How did you live the events before and after 1989? The two albums are structured by combining some vocal and instrumental recordings with reflections on these issues, delving into the personal and professional world of the artists and politicians summoned.

With a certain (n)ostalgic air, but with the certainty of a collapse announced by the structural failures of the subsoil, the majority agrees in the surprise with which the collapse of the country where they lived took them. As in May 1810, these people were caught by an unexpected and revolutionary event in history. On November 9, he found one in Australia, others in Leipzig and all of them, in need of adapting to the rules where state employment no longer applied. Until that day they had been civil servants for life in the bodies of the most prestigious theaters and orchestras. They were much more than a mark of the musical level of the conservatories in Dresden and Berlin: thanks to them the state of East Germany was nourished by the currencies that were so lacking. They went abroad - under observation - and, when they returned, half of the earnings went to the GDR coffers to guarantee, among other things, that the graduates of the conservatories had secured a job in a publicly supported theater or company, with performances always full, with tickets at ridiculous prices. One of the interviewees recalls that she had to wait for the fall of the wall to experience for the first time in her career what it was like to play in an almost empty room. The high cost of the seats, yes, but also the rules of a cultural market to which they were not accustomed and in which, without a doubt, they managed to survive thanks to the education they received.

Sadness is not absent from the voices recorded in 2009, nor is it absent from those who listen to it after rescuing it from the garbage container.

Kowalski, skinny and bony, has just retired from the stages of the Berlin Staatsoper where the audience that adored him in the 1990s - or at least some of them - still applauded him with affection, complicity and fervor. He retired in a supporting role, befitting a tired voice: the nurse to Octavia, Nero's wife in Monteverdi's Coronation of Poppaea. Happy, crowned with glory, they gave him a party in the basement confectionery after the farewell function. He was certainly unaware that someone had decided to throw that record out of his home with its oriental memories still fresh and that, by doing so, also without thinking about it, he was contributing to exponentially multiplying its character as a vestige of something increasingly remote in space and in time.

An alert that if we are willing to listen, reminds us that this is the end of everything alive, of everything human, of all nations, countries, states, cities.

It was not for nothing that someone was once told about the founding of Buenos Aires.

Death, after all, leaves more traces than births.

Bones. stones.

No more than that.

* Special for Hilario. Arts Letters Trades