The House of Indo-Afro-American Culture "Mario Luis López" [1] was founded in Santa Fe [2] by the marriage of Lucía Dominga Molina and Mario Luis López in 1988 and since 2002 it has been operating in their home. Despite economic problems and the loss of almost its entire library due to the flooding of the Salado in 2003, it is positioned as a benchmark in the (inter)national framework in this political field and, with more than three decades, it is the oldest Afro-Argentine institution working. Here I expand Afro-Argentine portraiture with a case study in four directions: authorial -it is the work of a single photographer-, spatial -those portrayed are from the "interior"-, temporal -it is contemporary-, and institutional -it is a self-managed undertaking.

State of the art

The study of his photographic portraiture of Afro-Argentines is scarce, including two academic articles by a professional, Alexander (2006 and 2007), in which he approaches it from case studies. There are also two brochures with photographs but without problematizing, with questionable selection criteria and almost all without data (Corrêa 2006, Parodi 2015). For my part, I analyzed the photographic collection of the Afro-Porteño singer and actress Rita Montero (515 pieces) [3], reproducing 75 of her in her book of her memoirs that I published with her (Montero and Cirio 2012). Considering various supports, I problematized how race and nation intersect in the corporality of Afro-Argentines portrayed in different times and contexts (Cirio 2007). I also discussed how the two class groups into which Afro-Porteños are divided -“negro usté” and “negro che”- are represented photographically, which helps to understand their respective value systems (Cirio 2016). Finally, I co-edited a book with Afro-Porteño Teté Salas, who shone as a dancer in revue theater and his performance in advertising, as a film, television and photo-novela actor, as a salsa and jazz teacher and as a candombe from Buenos Aires, allows us to understand the visibility of contemporary Afro-Porteños. In this framework I documented his photographic collection (212 pieces), reproducing 56 in our publication (Salas and Cirio 2022).

The Destefano Collection

José Alfredo Destéfano was born in 1965 into a middle-class home of Italian immigrants in the Sur neighborhood. Until his adolescence he had no greater cultural inclination than the enthusiasm for rock, although he was already interested in Afro and, with the availability of the time in a Mediterranean city, he tried to study it to the point of wanting an Afro-descendant partner. He made this happen when he met Mirta Ester Alzugaray, an Afro-Santafesina from the neighboring Centenario neighborhood, they moved to Arroyo Leyes in 2005. As an adult he studied photography at the Escuela Alem and, although he always liked cultural photography, he dedicated himself to living from this profession. to the commercial one, getting to have a local, although for a short time. His union with Mirta satisfied and strengthened his interest in the Afro. In 1988 they went to a Casa conference and became friends with Lucía and Mario, attending their activities first and collaborating later, although with ups and downs.

Gisela Luciana López, Mirta Alzugaray and Celia Stadelman. Old Willow. Photography: José Alfredo Destéfano.

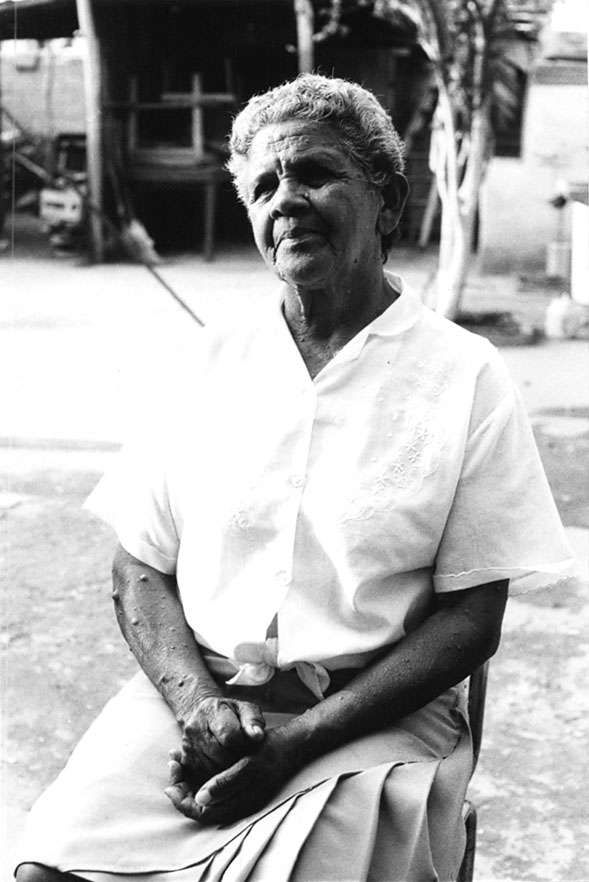

In January 1998, its founders, Mirta and José devised a photographic survey of Afro-Santa Fesinos, performing the role of photographer. Mostly those portrayed were members of the Molina-López family, friends and neighbors of Santa Fe and Sauce Viejo. They were sponsored by Boston Film, which donated the rolls and assumed the expense of developing, obtaining 70 pieces. The collection passed to the archive of the House, part of which was exhibited in the exhibition Mirror of a root. Afro-Santafesinos, forgotten but not disappeared in the City Museum, in 1998. Occasionally they used some in brochures, publications and the press. The flood destroyed them but the scrolls survived because Joseph had them. In 2013 Lucía lent them to me, I made new positives, scanned them and returned them to her with a digital copy.

Here there. from inside / from outside

As far as I know, the Destéfano Collection is the first on Afro-Argentines of the colonial trunk made intentionally and exclusively. As I said, unlike the native peoples, his photography has not been of great interest, although there are early antecedents by private commission, such as the anonymous daguerreotype Negra from the time of Rosas (Bs. As. c. 1850-2) and, by Olds, the Itinerant Fisherman (Bs. As. c. 1901), because, although European or Euro-descendant, he posed in front of an Afro family. I selected both examples because they did not record the names. As an exception, that of the oldest known sitter, Juan González, steward of the Stock Exchange, who identified Vertanessian (2019) in the daguerreotype "El Camoatí - Stock Exchange", by Smithson (Bs. As., 1854). This repositioning is not minor if we want to know this group qualitatively, based on their identities and that they are citizens by right.

With the motto "Afrosantafesinos, forgotten but not disappeared" the House showed part of the Destéfano Collection in its exhibition Mirror of a root at the City Museum in 1998. The distributed triptych has this text:

“It is not easy, in Argentina, to carry a skin that does not correspond to the idea that generations desired, and that the founders of our supposed nationality bequeathed as an incontrovertible and revealed truth.

Being Afro-Argentine, here in this country, where many want to be what they are not, and where many end up being nothing, is something that borders on the incredible, and that makes us blacks feel like foreigners in a land that our parents , our grandparents, our great-grandparents and our great-great-grandparents collaborated to build with their sweat and blood, and where not only has our presence and our contribution never been recognized, but this has been systematically bequeathed and ignored.

Such denial, so deeply ingrained in recent years, seems to have transformed our society into a monster that does not recognize parts of its body or its head; who doesn't even know that it exists. By detaching ourselves from our roots, we are like leaves that the wind drags, with no possible future: domination grass.

That is why with this humble exhibition we want to show our presence and our reality, in front of the many who for more than a century happily announce that we do not exist. Logically, the last four centuries have washed our faces and our skin, victims of who knows how many rapes or how many clandestine and subversive loves, but here we are, with more or less visible phenotypes, but with the indelible mark of Africa and of our ancestors, who do not leave us alone and want to shout their longing for freedom through us, THE DESCENDANTS OF THE BRAVE AFRICAN SLAVES WHO CONTINUE FIGHTING FOR FREEDOM AND EQUALITY FOR ALL. For ALL of us."

The first person plural gives life and marks the importance of the group that unites them as Afro-Argentines and that the House tries to serve by exhibiting portraits of contemporary Afro-Santa Fesinos in their city. It is an iconic-discursive empowerment that revalues an aspect little attended to by the hegemonic groups in power by imparting what is possible to remember, recall and historicize via the pillar institutions on which every Nation-State legitimizes itself before the citizenry: the museum, the census and map (Anderson 2000). Thus, the House positions itself proactively by tending the ties of social memory (Halbwachs 2011) cut to favor the imaginary of a white country in skin and culture since the end of the 19th century, being aware that such work is undertaken, following Jelin (2002), not as "memory against forgetting" but "memory against memory".

Photography, far from being limited to the conservative conception of entertainment and reflection of reality, carries ideology. Regarding its use by hegemony, Burke (2001) showed that it is manipulated. As with speech, the way in which the content is framed also conveys its message and this was its greatest question, which is why the definition of photography by Barthes (2006: 83), “thinking eye”, becomes relevant. The exotic charge that usually covers the portraiture of marked groups had its stereotyping as a substitute. Destéfano, sensitive to the work of the House, made the analyzed collection portraying Afro-Santa Fesinos in their contexts. Although few were spontaneous, far from being unnatural, it demonstrates the care of its construction. They sought the immediacy of everyday life, ensuring that the eye that thinks can be transposed to the neighboring eyes of those who posed to understand them as descendants of enslaved people, de-essentializing common places such as black skin, denouncing that such whitening was not natural. For Sontag (2021), if photography does not capture reality, it is an interpretation of the world, then this collection bears witness to a topic about which society is still little aware today, the contemporaneity of Afro-Argentines.

Photographing is more than passive observation, it does not account for reality, it creates it, transcending the spontaneous by fixing a certain image, from a certain frame, with a certain language, for posterity. “Photographs cannot create a moral position, but they can consolidate it; and also contribute to the construction of one in the making” (Sontag 2021: 27). As the Destéfano Collection is an institutional project, it invites viewers unaware of the subject to rethink their common sense. This is ideology and the House knew how to use it in its policy of recognition. The emotional weight of the photographs was always valued by the social actors involved and they are complemented by experiences and conversations. It was no coincidence that the first four belong to Mercedes Molina, Lucía's first cousin, esteemed for her knowledge, such as Afro religiosity. If “Photographing is conferring importance” (Sontag 2021: 36), the collection appraises those who have been forgotten, silenced, denied, made invisible. The eye is the organ by which the world becomes a representation in the mind, plus photography, as a representation of the photographer's world, needs to sensitize the viewer. The quote from Barthes that opens this article addresses the issue, complementing it with the oxymoron that “to close your eyes is to make the image speak in silence” (Barthes 2006: 94). Lucía captured it to understand herself-in-the-world in the poem Veo:

I close my eyes…

I look for my past

not mine, yes ours.

That forgotten grandfather

That distant grandmother;

that rumble - rumble

in my heart.

Destéfano tried to raise awareness. If Afro-Argentines were the object of study and some portrayed them under the Western canon that founded this art, such as picturesqueness or the pseudo-scientism of craniometry at the service of disciplines apparently dissimilar in origin, criminology and anthropology, with this project The House took advantage of photography by incorporating the creation of a document of the local present into its visibility policy, which fed back its work by exhibiting it and using it in brochures, the press and bibliography. From there they passed to here, from the outside to the inside... from an object of study to a subject of law. Sontag (2021: 114) points out that they do not explain, they recognize and "to produce an authentic contemporary document, the visual impact would have to be so strong as to nullify the explanation". Ergo, the House created this collection that declaims the contemporaneity of Afro-Argentines. Militants of identity, with this collection they reposition themselves socially, raising awareness towards a new understanding of their ontology.

Children and grandchildren of Horacio "Snow White" Rodríguez. Photography: José Alfredo Destéfano.

This transition towards visibility by empowering photography to preserve places, faces and memories is a practice of recent and growing use in groups marked by otherness. Thanks to the work of the House in my first fieldwork, in 2006, I interviewed Miguel Ángel Ramos (in 11 pieces). He was a hairdresser and directed a folkloric ballet. He owes his identity construction as Afro-descendant to his maternal grandmother, who told him about her ancestry, remembering the mistreatment of his elders. She was Mercedes Simeona (Santa Fe, 1887), daughter of Carmen Lavaca, who migrated from the Güemes neighborhood of Córdoba, at that time mostly populated by Afros. Others are from the Rodríguez family, nicknamed Blancanieves, from the Santa Rosa neighborhood (13, in 6 pieces), and the review of works by third parties may yield findings. In Tire dié (1956-58), by Fernando Birri, there are several Snow Whites because he filmed it, precisely, on the Salado coast when passing through that neighborhood.

Conclusions

Thus began Carl Einstein's Methodical Aphorisms (1929: 32): "L'historie de l'art est la lutte de toutes les expériences optiques, des espaces inventés et des figurations." Are we, with the Destéfano Collection, at the dawn of a new visual experience, that of the self-perception of Afro-Argentines?

I consider that the value of the Destéfano Collection lies in four questions, according to the directions proposed:

1. It is from a single photographer, achieving a unity of original thematic and aesthetic sense in a limited period and scope.

2. Unlike most of the photographs of Afro-Argentines, which are from Buenos Aires, these are from the “interior”, the cities of Santa Fe and Sauce Viejo.

3. Although the old photographs are appreciable for being beautiful and providing diverse information, having contemporary ones positions the group in presentist coordinates that the citizen's imaginary rarely admits.

4. It is an exemplary case of empowerment from an NGO in the right to account for this group from its subjectivity. Since the human being does not use sight in a universal way, it positions it as a valuable source to study Afro-Argentine visuality.

Outside of all folkloric fetishism, those involved were portrayed in their contexts, which helps to de-exoticize Afro-Argentines by positioning them as fellow citizens. There was also interest in showing the stages of the life cycle and its phenotypic diversity. Knowing part of the country studying Afro-Argentine culture, I can affirm that society only accepts him if his phenotype coincides with its prejudice. Due to several factors, this type of Afro-Argentineans is a minority, therefore, not representative, so the Collection helps to denature them.

If “All photography is a certificate of presence” (Barthes 2006: 134), here I analyzed a contemporary collection that seems unique. We still do not know much about the Afro-Argentines of the colonial trunk, so I hope that it is neither the first nor the only one.

Notes:

1. Hereinafter the House.

2. Unless otherwise indicated, all events occurred in Santa Fe.

3. In my file by his will after he passed away, in 2013.

Bibliography

- Alexander, A. 2006. Retratos en negro: Afroporteños en la fotografía del siglo XIX. Memoria del 9º Congreso del Historia de la Fotografía. Rosario: Sociedad Iberoamericana de Historia de la Fotografía, p. 29-36.

- 2007. Retratos en negro: afroporteños en la fotografía del siglo XIX. Historias de la Ciudad 40: 6-19.

- Anderson, B. 2000. Comunidades imaginadas: Reflexiones sobre el origen y la difusión del nacionalismo. Bs. As.: FCE.

- Barthes, R. 2006. La cámara lúcida: Nota sobre la fotografía. Bs. As.: Paidós.

- Burke, P. 2001. Visto y no visto: El uso de la imagen como documento histórico. Barcelona: Crítica.

- Cirio, N. P. 2007. La música afroargentina a través de la documentación iconográfica. Ensayos 13: 126-155.

- 2016. Negro que no toca “cuero” no es negro. La construcción de la identidad social afroporteña a través del tambor. Vestígios 10 (1): 51-70.

- Corrêa, Á. 2006. A los negros argentinos salud! Bs. As.: Nuestra América.

- Einstein, C. 1929. Aphorismes méthodiques. Documents 1: 32-34.

- Halbwachs, M. 2011. La memoria colectiva. Bs. As.: Miño y Dávila.

- Jelin, E. 2002. Los trabajos de la memoria. Madrid: Siglo XXI.

- Montero, R. y N. P. Cirio. 2012. Rita Montero. Memorias de piel morena: Una afroargentina en el espectáculo. Bs. As.: Dunken.

- Parodi, N. 2015. Afroporteños. Bs. As.: s/d.

- Salas, C. y N. P. Cirio 2022 TT Salas 777: Una historia viva de la revista (afro)porteña. Bs. As.: 13 Mil Pájaros.

- Sontag, S. 2012 Sobre la fotografía. Bs. As.: Debolsillo.

- Vertanessian, C.2019b El Camoatí: El daguerrotipo argentino que fue noticia en el mundo. Histopía 1: 84-111.