"On the 14th of last afternoon - announced the Diario de Madrid of 1792 - at one of the doors to enter the stalls of the Plaza de los Toros, a bag for tobacco was lost, made of a sea lion, with an embroidered lining. of silver, and several papers inside, and among them some receipts and an account, all of consideration; whoever found it will deliver it to the Hon. Mrs. Widowed Countess of Puñonrostro, who lives on the wide street of S. Bernardo next to El Salvador.”

Five years earlier, but on Calle de Atocha, Joseph Aguerre, who lived opposite the Prince's Regiment barracks, had lost another, in this case, lined in white with fine sequin embroidery. And on the 11th, Joaquín Rodríguez Costillares lost a third, this one with plain satin lining, gold embroidery, milk-colored ribbon and gold; at some point along the route that went from Calle de la Rua to the Soto de Migas Calientes baths. Barcelona suffered from the same epidemic, where a certain Agustín Pallares lost his sea-dog wallet with various papers.

The wolf bags, in addition to being lost, were also used to identify the dead and the living. In the inventory of the assets of the deceased Duke Don Álvaro de Zuñiga, two belts made with this material were counted, one narrow and the other to be mounted with its esqueroina and navajón and a silver gate. And in a trial, exemplary for the criminal practice of the peninsula, the reserved testimony of Pascual Buendía reported that the tall man whose body had been exposed to the public at the door of the Madrid prison, in life had sold sea lion bags to tobacco at the fair near the plazuela de la Cebada. He recognized it for them. And for his old velvet and white canvas breeches, objects that appeared on the street of Chinchilla in the possession of the waiter of the Andalusian inn along with a pair of old jargon saddlebags and inside them, thirteen wolf skin bags for tobacco and other eight somewhat older.

This is not surprising: in the 18th century, instead of a pouch, the tobacco was kept in a wolfskin bag, which was bulging in the crotch of the trousers, with a tail sticking out of it somewhat through the pouch. (1) The murdered man, as can be seen, was engaged in the trade of these skins, which were also used for blankets for the four-wheeled barouche. They were sold on Calle del Príncipe and, in sheet form, in the description of the Royal Cabinet's collection of animals and monsters. In charge of the Valencian preparer Juan Bautista Bru -the same one of the corpulent and rare animal later called Megatherium-, these were in the Copin bookstore, at 50 reales without illumination, at 80 illuminated in the paperback and at 90, in paste. The gazettes, the mercantile almanacs and the commerce did not fail, for their part, to include the report on the transfer of sea lion hides and to remember that, like those of alpaca and skunk in carpets, they were duty-free at their exit. To the exterior. On July 29, 1785, the urca of the Real Armada Santa Florentina arrived in Cádiz, coming from Montevideo with 409 rolls of black tobacco for H.M., 5,661 hair hides, 2,725 sea lion skins, 329 arrobas of vicuña wool and ram. Before, on July 8, 650 wolf skins brought by the Saetía San Antonio de Padua had already been used to make those things that seemed to fulfill the designs of Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo in his description of the animal called "sea wolf" in his General History of the Indies:

“But because it is a thing to note what I will now say about this sea lion animal, I say that the ribbons and straps that are made of the leather of the sea to gird men or for bags or for what they want, that when the sea is low, the hair is flattened, and when it is high, it rises. Thing is very experienced, and that in any tape or part of the skin of the sea lion is seen every day; And all the changes that the sea makes are known in the hair of these animals. Because of which I believe, and because of what was said about their use of childbirth and children who raise their breasts, that those we call sea lions are the same ones that Pliny calls an old sailor in his Natural History. In addition to this, the common people say that, for those sick with pain in the loins, these waistbands made of the leather of these wolves are very good: it is true, they look good to the eye, especially those that are black and made of old wolf, because they are more populated with thicker hairs. And this is enough for the sea lions of these parts.” (2)

And not to mention that Bartolomé de las Casas, the enemy of Oviedo, knew very well the characteristics of these animals and the properties of their skins: when commenting on the exploitation of the indigenous people in the pearl fisheries, he compared their appearance with the skins of these animals, whom they ended up resembling as a result of the marine life they were subjected to:

Because it is impossible for men to live under the water without breathing for a long time, especially since the cooking coldness of the water penetrates them. And so everyone commonly dies from bleeding through the mouth, from the squeezing of the chest that they do because of being so long, è so continuous without breath, and from chambers that causes coldness «the hairs become black, being of their nature, burned like the hair of sea lions, and saltpeter comes out of their backs, which do not seem but monsters in the nature of men, or of another species. (3)

The Indians thus ended up turned into sea lions, those animals between amphibians, fish and women, whose fishing or hunting, much later, the Courts of the 19th century would regulate along with pearl diving and whale fishing.

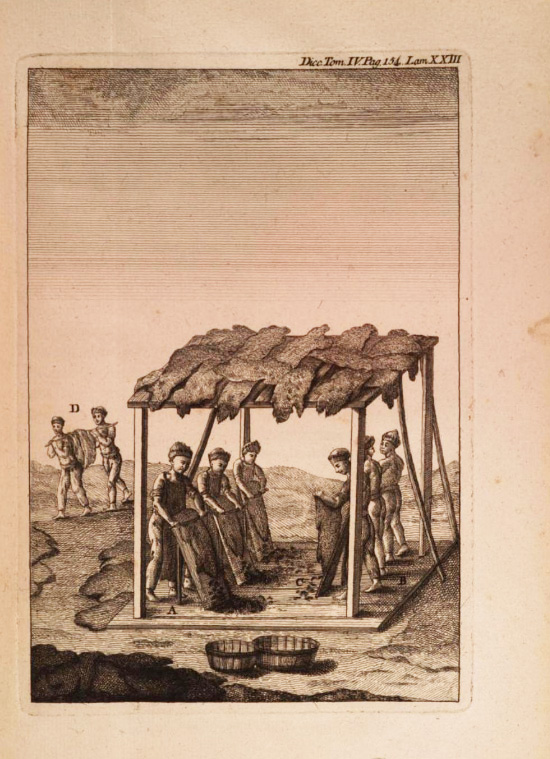

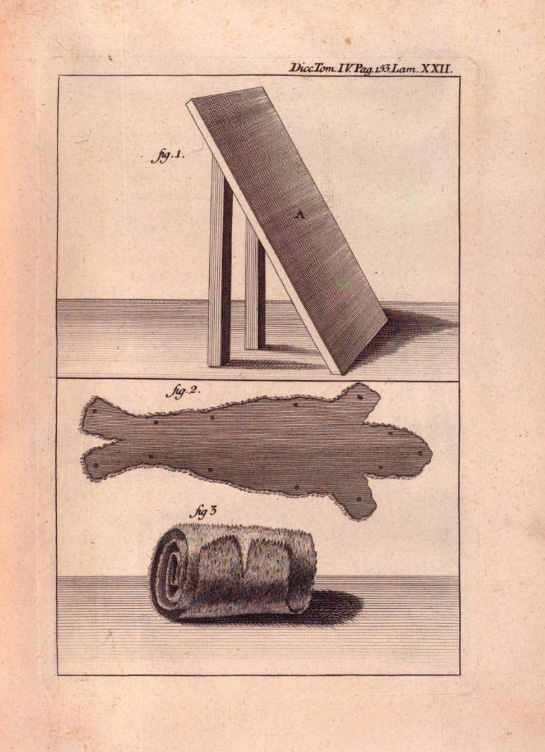

Once prepared, the skins are transferred to "tend and stake." (Engraving.: In Antonio Sañez Reguart: ob. cit. Madrid, 1798)

Far from a destination, between those sixteenth-century descriptions and the eighteenth-century uses of sea lion skins, mediated the history of the economic occupation of the southern American world. The fishing or hunting of "sea lions", a term that in Spanish until the 19th century designates various water mammals, was consolidated as a collateral activity to whale fishing. And this, at least in the Atlantic and the South Pacific, as a pretext for the English - new and old, real or insurgent settlers - to hide the direct trade that the ships of those flags established with the cities of the Indies. Something that the Spanish called contraband and that prospered by avoiding the taxes that the commercialized products paid when entering and leaving the peninsula. Behind the shadow of an English whaler or wolfhound, viceroys and mayors saw a smuggler.

Navigation, fishing and hunting of marine mammals are as linked to the history of humanity as life on dry land. In the Spanish Monarchy, the fishing of whales and seals or sea lions is, however, an activity promoted belatedly, linked to the reforms of the Bourbons and to the expansion towards the north in the Pacific, towards the south in the Atlantic and above all, to the attempts to stop what from Madrid, in the 18th century, is perceived as contraband disguised as fishing. In 1789, the Maritime Fishing Company was created by Royal Decree for the fishing of whales, sea lions and sea lions and the establishment of factories on the Patagonian coast. The Port of Maldonado in the Banda Oriental was enabled in favor of it so that the ships could register the effects that they carried from Europe and the fruits that they carried on their way back. Between 1796 and 1799, 26,484 sea lion hides were obtained between Río Negro and San José. The Royal Maritime Company, belonging to His Majesty, was located at Carrera de San Gerónimo 6, in Madrid, in front of the Nuns of Pinto: the person in charge was D. Alberto de Sesma, Knight of the Royal Order of Carlos III, Brigadier of the Navy and the Council of War, seconded by the secretary Juan Antonio Aresti, the accountant Joseph Antonio de Arana and a treasurer.

The boiler where the fat extracted from the animals is prepared is protected under another shed. (Engraving.: In Antonio Sañez Reguart: ob. cit. Madrid, 1798)

In those years, the attempts to control smuggling in the seas of South America generated several initiatives to promote the Spanish fishing of whales and sea lions. But debates also arise about the exploitation and hunting of sea animals that refer to the property regimes of wild beasts in two areas of domain as controversial as the ocean sea and Atlantic Patagonia in a journey that leads to the common good to the privatization of the beasts that are hunted. A key problem linked to the domain, control and existing right over the wild fauna of the sea and the land and the conflicts that arise when the colonial ties with Spain are broken, a subject little studied in the bibliography until now.

The Maritime Company and the fishing of whales and sea lions have appeared in Argentine history linked to the exhumation of colonial documents to prove, based on iutis posseditis, Argentine rights to the Patagonian coast and the Malvinas Islands. Reading these documents from the sea and from the history of the exploitation of its fauna show that coast and those lost islands as a political problem in part thanks to the animals and the interests in exploiting them. But it also serves to read the history of 18th-century zoological classification as part of that process: contrary to the idea that the Linnaean system excludes the usefulness of animals to humans as a criterion for ordering them, the idea and name of “ferae ” (feral) – where Linnaeus places seals and pinnipeds in general – seems to suggest a certain kinship with the legal debates of the time: the law over ferae naturae, wild animals, subject to hunting and fishing. These provisions on the wild animals of the sea had to be reformulated in the era of the expansion of oceanic navigation and – needless to say – of steam navigation. Oceanic “fisheries” not only began to be regulated as the property of the States, but also – in the case of marine mammals – passed from the realm of regulation of fishing to regulation of hunting. And this in a context where at the same time the classification of these animals (cetaceans, pinnipeds) as mammals and not as fish, a class in which they were until the middle of the 18th century, was being discussed. The South Atlantic, seen from the sea, becomes a fundamental setting for environmental history, a perspective that questions the peripheral place it still has in historiography.

Notes:

1. Serafín Estebánez Calderón: Cigar physiology and jokes, in Andalusian Scenes, Madrid, 1847, 320. And Catalog of the collection of tobacco boxes and smoker's utensils, General Directorate of Fine Arts, Museum of the Spanish People. Electronic reissue, 2011, p. 16

2. General and natural history of the Indies, islands and mainland, by Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo, p. 429.

3. The Works of Bishop D. Fray Bartolomé de las Casas, p. 35.

The images that illustrate this article were obtained from the work Historical dictionary of the arts of national fishing. By the Royal Navy War Commissioner Don Antonio Sañez Reguart. Madrid. 1793. Volume 4.

* Extract from a chapter by the author published in “En el mar austral. The natural history and exploitation of marine fauna in the South Atlantic”, book edited by Susana V. García (Rosario: Prohistoria, 2021)