The man

Bartolomé José Ronco was born in Buenos Aires on July 7, 1881. His parents were Juan Ronco (native of Genoa, died in 1902), a merchant based in the Buenos Aires neighborhood of San Telmo, and Manuela Díaz (died in 1923). In 1903 he graduated as a lawyer from the Buenos Aires Law School. He knew how to divide himself between his necessary and absorbing professional occupations and his intellectual concerns. On November 12, 1908 he married María de las Nieves Clara Giménez, born in Azul on May 2, 1886, daughter of Evaristo Giménez, a Spanish rancher in the region, and María Leontina Brital, French. They had a daughter, Carlota Margarita, who died as a teenager.

Since 1929 he was a corresponding member of the Board of American History and Numismatics (later National Academy of History), which he joined on May 17, 1930, he was part of the Argentine Society of Writers [1] and the Friends Society of the Archeology of Montevideo. In November 1947 he was appointed honorary delegate of the National Commission of Museums and Historical Monuments in the central and western region of the province of Buenos Aires, based in the city of Azul, due to the importance of said region "in historical traditions" [ 2]. Known in the cultural environment of his time, he had regular contact with historians (Ricardo Levene, Ricardo Piccirilli, Enrique Udaondo, Ernesto Celesia), lexicographers (Amado Alonso, Eleuterio Tiscornia), diplomats (Alfonso Dánvila)[3], collectors (Antonio Santamarina and Oliverio Girondo), writers (Pablo Rojas Paz, Arturo Capdevila, Jorge Luis Borges, Eduardo Mallea, Rafael Alberti), anthropologists (Robert Lehmann-Nitsche, Enrique Palavecino), traditionalists (Martiniano Leguizamón, Félix San Martín) and ethnic scholars aboriginals (Juan Benigar) [4]. The Cuban poet Nicolás Guillén, who visited him in Azul in 1947, would remember him in his memoirs as “a man of much travel and much reading” [5]. He died in Azul on May 6, 1952 [6].

His intellectual and institutional work

After working in Buenos Aires in the law firm of Dr. Francisco Crotto, since 1905 he was secretary of the Court of Appeals of the Judicial Department of the Costa Sud (Bahía Blanca), and one of the founders of the local Bar Association. In 1917 he settled in Azul, where he was the most prominent figure in the local forum [7]. In 1941 he retired as a lawyer from the Banco de la Nación Argentina, culminating the cycle of his tireless professional work.

His intellectual and institutional concerns came from his father, author of journalistic articles, booklets and conferences, precursor of Sunday rest and founder of the first free Buenos Aires nocturnal commercial academy: the Cosmopolitan Society for Mutual Protection and Instruction, established in the Capital Federal on July 23, 1876, which developed an intense mutualist work and an important work of general culture in its own headquarters at Chacabuco 1072, between Humberto 1° and Carlos Calvo, where a library also operated, to which in 1924 it was imposed the name of "Juan Ronco", declared public [8], whose board of directors in 1932 was made up of Beatriz and Juan Carlos Ronco, brothers of Bartolomé [9].

In Bahía Blanca he dedicated a lot of effort to the "Bernardino Rivadavia" Popular Library of that city, founded by Juan Caronti. Germán García describes the period during which Ronco held his presidency as revolutionary: «This is, by the way, the most appropriate adjective that the exercise of 1915 deserves. Until then, the Library had carried out its work in a modest way, without leaving its four walls as they say. But Dr. Bartolomé J. Ronco arrived and things changed: if the members did not come alone, we had to go look for them; If money was needed to build shelves, buy books or make catalogues, they went out into the streets to get it from those who could give it. A new classification and inventory was made of all the bibliographic material, all the works were cataloged and there was even serious thought about opening branches […] A man of extraordinary dynamism, Dr. Ronco gave the library the stamp of his own personality, in only one year that passed by her. He personally won over new associates and was responsible for obtaining important cash donations. Of course, when it came to raising a promissory note from the Association or paying bills, he did not resort to looking for money where there was none: he expected a lawyer to have good fee regulation and directed the job there. The medium did not fail […]. In December 1915, Dr. Ronco finished his mandate, immediately leaving for Azul. Dr. Francisco Cervini was appointed president to replace him »[10].

Founded on May 8, 1892 as an autonomous civil association, created by the initiative of a group of neighbors who directed and administered it, and with legal status by decree of 1902, the Popular Library of Azul offered the service of a consultation space and reading in a broad, free and pluralistic way. It was one of those in the province of Buenos Aires that, since its foundation, had been luckier in successive administrations since it had its own house, a circumstance that turned it into "a temple of the book," and it was not long in coming to be considered first category by the Popular Libraries Protective Commission. Ronco joined his board of directors in 1923 and on June 15, 1930, the members' assembly elected him president of the institution, a position he held until his death in May 1952 [11]. Ronco promoted the various special sections of the Popular Library: children's, prison, newspaper library, collection of articles and clippings by Argentine writers, collection of prints, cartographic archive, ethnographic museum and historical archive. In August 1948 he organized an exhibition of bibliographic material from the Azuleña printing presses: books, pamphlets, newspapers, and periodicals [12].

On May 11, 1948 he was honored at the modern San Martín Cinema Theater for his cultural work and on the occasion of his re-election for the 10th consecutive period as president of the Popular Library of Azul [13] .

He believed in the dignity of women, in the protection of helpless children, in the value of education (and for this reason he promoted the creation of the "José Hernández" Popular University in Azul, for the teaching of trades, which operated for many years in the Bolívar building between Burgos and De Paula, currently occupied by the Faculty of Law of the National University of the Center), in the popular dissemination of the book through libraries, and of traditions through museums, of a culture at the service of everyone and not limited to small groups with elitist whims. He was also the owner-director of the magazine Azul de Ciencias y Letras (1930-1931), today a rare collector's item, which managed to publish eleven numerous issues [14].

Origin of your collection

On April 19, 1930, Ronco wrote to the collector Carlos Guillermo Daws: «I already knew you by name and I also knew your passion for Creole things and customs since I had read the articles that appeared in the magazines Nativa and El Hogar. In this area, you have an imitator in me, since I have also formed a museum of things that refer to our rural customs and our indigenous past" [15]. On September 10, 1931, the Buenos Aires newspaper La Prensa, in an article illustrated with photographs, reported: «In his travels through the provinces and neighboring countries, Azul's neighbor, Dr. Bartolomé J. Ronco, has gathered a varied and interesting collection of objects from the more diverse in nature, but which all refer to the ethnography of distant regions and towns in America. That collection will be the basis of a museum” [16].

Walter Benjamin reflected in his Interrupted Discourses that "great collectors are often distinguished by the originality with which they select their objects," and in truth that was a distinctive characteristic of Ronco when forming his select collection that included the items that I now refer to. .

In the field of Creole silversmithing, reins, bridles and sureties from Entre Ríos stood out; leg brakes, from pontezuela from Azul, Olavarría and Entre Ríos (19th century); heads for clubs; stirrups (from Tres Arroyos and Rosario) with bow, piquería, brazier and shoe, stirrups; tinderboxes; mates (4 from Chile, 3 from San Luis, 2 from Buenos Aires, 2 from Mendoza, 2 from Tucumán and others from Córdoba, Salta, Jujuy, 2 from Tucumán, and others from the province of Buenos Aires -Las Flores, Lobos, Azul-, Concordia and Bolivia); blue scraps and buttons (three with gold inlays), from Tandil, Saladillo, Bolívar, Neuquén, Santa Fe and Uruguay; handles and tips of facón, dagger and knife sheaths. This was completed with calabash mates, Spanish stirrups (two from the 16th century, one made of bronze acquired in Valdivia, Chile in 1925, another grill, made of copper, and others from the 19th century), English, French, and also soles ( from Azul, from San Antonio de Areco and from Corrientes) made of box or wood (Mendocino and Chilean from Chillán) and sole and leather from Salta; iron spurs, bronze and silver and bronze Chilean spurs, for mules from San Luis, thread and leather girths (from Rio Negro and the mountains of San Luis), padlock brakes (from Concordia and Olavarría), a pair of authentic pony boots, from Lobos, belonging to a soldier from Rosas, acquired from his daughter in 1914, a mortar and carob handle from Yacanto (Córdoba). Bladed weapons and firearms with percussion and repetition, banknotes, coins, medals and autographs. This should include the drawings and paintings (tempera and watercolors) of country themes made by Evaristo Giménez (Ronco's father-in-law), exhibited in Azul on March 15 and 20, 1948 [19] and also in the Witcomb Gallery in Buenos Aires.

The ethnographic material included three sets of pieces: one of Pampas and Mapuche silver jewelry for women's use acquired in Temuco (Chile) in 1925 [17], another of Bolivian silverware from the 18th century, and the third of textiles, which included two genuine pampas ponchos from Azul (one of which dated from 1878), a pampas blanket from the Rio Negro (1930), Chilean Mapuche sashes, tobas, languages from Paraguay, Catamarca and Santiago.

He also had an important collection of porcelain and ceramics, which he exhibited publicly in Azul in 1938. American ceramics were represented by potteries from northern Argentina, the Diaguita civilization, the Calchaquí Valley of Catamarca (most of the pieces, about 70, anthropomorphic and zoomorphic , had belonged to the lawyer and amateur archaeologist Adán Quiroga), vessels from Nazca and Trujillo (Peru, Inca civilization), vessels and timbales from Tiahuanaco, ceramics of indigenous origin (Mapuche, Toba Indians, northern Paraguay and Brazil), popular ceramics (from Córdoba, Salta, Jujuy, Paraguay, the Bolivian highlands, and fired clay from Neuquén). The rest were porcelain and earthenware of Spanish, French, English, German, Italian, Belgian, Austrian, Danish, Dutch, Tunisian, Chinese and Japanese manufacture, from various periods [18].

The Library

At his home at San Martín 362 (Azul) he occupied three rooms and was divided into three sections: the legal section, the history and ethnography section, and the literature and philosophy section. It consisted in total of about 10,200 bound volumes, excluding pamphlets, of which he had had a large collection that he acquired in 1930 at the auction of what had belonged to Estanislao S. Zeballos, and donated a large part of it to the National Library ( those of a religious nature, from the 19th century and belonging to various countries in America) and the rest to the Popular Library of Azul, where they are preserved bound.

Ronco's library had its origins in a set of legal works and encyclopedias that his father gave him when he was a student. Many of his books were acquired by purchase from the bookseller Julio Suárez (owner of the famous “Cervantes” bookstore, located in Lavalle between Florida and San Martín), the rest were acquired in different bookstores in Buenos Aires and at auctions in private libraries [ twenty]. In a letter to Domingo Buonocore in 1946 he expressed: «I do not have the spirit of a collector. I love the book for its content. I'm attracted to a deluxe edition but it doesn't seduce me. This means that I have never paid greater attention to bibliographic externality” [21].

The legal section occupied a large room to the right of the entrance hall, where some 2,500 volumes were lined up, which after his death his widow sold to the Azul Bar Association (it included the complete series of rulings of the Supreme Court of Justice National and Provincial and compilations of laws, ancient and modern).

The History and Ethnography section was made up of approximately 3,000 volumes, with an abundance of documentary collections, general histories and travelers' accounts. In this section, works on regional history and on the Indian and the gaucho stood out.

The rest of the material was grouped in the Literature and Philosophy sections, highlighting a large group of important Argentine and foreign magazines. The Literature section contained, in turn, the copies of Martín Fierro and the works that refer to the author and the poem, and those of Cervantes. All this was completed with an archive of newspaper clippings, prints, facsimile reproductions and other graphic motifs, both about Hernández and Cervantes, material gathered and classified in book folders.

Martin Fierro Collection

He owned almost all the editions of the poem, both those of the first part and those of the second and those of both together published in our country or abroad. He had a copy of the prince of El gaucho Martín Fierro, published in Buenos Aires, by the printing press of "La Pampa", in 1872; It belonged to Estanislao Zeballos and contains corrections in the author's handwriting. It came into his possession through a purchase he made on August 18, 1928 from Mr. Julio Suárez, owner of the Cervantes bookstore, who had acquired it from a son of the owner of it. In addition to the corrections made by Hernández in the text, some shorthand signs are noted that, surely, were drawn by Hernández himself (it is known that the poet wrote in shorthand). Ronco only knew four other copies of this edition, two that are preserved in the National Library, and the rest in the possession of Eleuterio Tiscornia and Guillermo Moores, respectively. In twenty years of searching he was unable to see any copies of the third, fourth, fifth and sixth editions of the first part. Antonio Santamarina once showed him a copy of the octave. Ronco possessed the seventh, eighth, ninth, tenth, eleventh, and twelfth editions (with this last one ended the editions published during the author's lifetime, those that followed are clandestine and of them he had the 14th and the 15th).

He also had a copy of the first edition of the second part (The return of Martín Fierro) published in Buenos Aires by the Pablo E. Coni Printing Office, in 1879, which also belonged to Zeballos and on the back of the cover and written The following dedication is read by its author: «Mr. Dr. D. Estanislao Ceballos. Gift from his affmo. and old friend, J. Hernández. The dedication is written in four lines. No matter how much he inquired, the news of the existence of another did not come to his knowledge. It also had several editions of the second part and all the complete or fragmentary editions after the death of the author and his translations.

As for the copies of both princely editions, they are still in optimal condition today.

On June 28, 29 and 30, 1931, from 5 to 8 p.m., Ronco exhibited his collection in Azul, an opportunity in which books, engravings, autographs, printing plates, covers, maps, portraits, card games and objects were exhibited. related to our national poem [22].

Cervantine collection

In this section is the collection of works by Cervantes or that deal with him: a total of 1,000 volumes and pamphlets that include 320 editions of Don Quixote, dating back to the 17th century and including those known from Antwerp (1719), Ibarra (1780) , London (1718), Paris (1836-37), Barcelona (1892). In the opinion of its owner, it was the most valuable thing in his library, which in 1932 he exhibited in Azul [23]. On April 11, 1947, he wrote to the Uruguayan Cervantist Arturo from the 18th century, a larger number from the 19th century, many others from the current century and all those published in Argentina. The one I value most is the first Spanish edition published in London by Tonson in 1738. It is a copy in perfect condition, unlike any I have seen in the collections I know. I also greatly appreciate the one published in two volumes and in Paris with the original plates by Gustavo Doré. I have also collected and preserved in one hundred and fifty folders, mounted on cardboard, all the cuttings from newspapers and magazines I have managed, that refer to Cervantes, his works or topics related directly or indirectly to one or the other. I have also collected all the plates and illustrations of Don Quixote. In this regard, the person who can give you news about my collections is the cartoonist Toño Salazar, who resides in that City at 1060 Santiago de Chile Street, and who, commissioned by the Losada publishing house, will illustrate a monumental edition of the Quixote, which will surely appear within one to two years, according to the news that Mr. Salazar has given me. And on April 15: «By this same email I send you the Catalog of the Cervantes Exhibition, held in this city in 1932, at the initiative of the Popular Library. All the material that appears in that catalog is today in my Library, but significantly increased, since, after the date of the aforementioned Exhibition, I acquired numerous editions of Don Quixote and other works by Cervantes on my trip through Spain, France and Italy".

Carlos Alberto Pueyrredon had collected 400 different editions of Don Quixote in his house at 2525 Las Heras Avenue (Buenos Aires). Ronco, without reaching that number and quality, was recognized as a Cervantist [24] by Juan Sedó Peris-Mencheta, who on March 14, 1948, in his public incorporation speech to the Academy of Good Letters of Barcelona, recalled: « I owe to my good friends Don Arturo E. volumes in total, containing some 350 editions of Don Quixote (3 from the 17th century) in various languages and a rich iconography of the same work" [25].

Collection destination. The Ethnographic Museum of Azul and the legacy of its private Library

In April 1940, Ronco presented to the Popular Library that he presided over, his project to install a public museum that would house materials related to the history, folklore, industry and commerce of Azul and its area, with the name "Enrique Squirru." » which was approved on October 1. On the occasion, it was decided to acquire the property located in San Martín y Alvear (today Bartolomé J. Ronco), which dates back to 1854, resolving that it would be managed by a Library commission. On October 23, he wrote to his friend, the well-known jurist Antonio Aztiria, about the difficulties that his planned museum had to face: «Here I am in the new undertaking of installing a Public Museum, and I suppose you have already received the circular note that has been sent to all Azuleños residing in the Federal Capital. I cannot hide the enormous sum of selfishness and prejudices that I will have to overcome; But, I will go out to shore, and the dead friend [Enrique Squirru] will have the modest tribute that he deserves. Out of sympathy for all those who love me badly, I want to bring to the people of this place the concept that death should not be a definitive fact and that, beyond the missing man, there must remain gratitude shown. The house is bought; God will now tell you how I pay for it. The house costs six thousand pesos and I calculate the same for the new constructions; but the Museum will open, even if the creditors are its first visitors and even if there is the harsh order of the arrival of a bailiff with a seizure order. […] Everything I have at home, enough to be included in a museum – myself excluded – will go to the Museum. The time is coming to let go of things; because it is kinder that one assigns them destiny and not judicial brackets. I will be very curious to perceive the attitude assumed by some of Squirru's friends. The first donation received was from Alfredo Fortabat. I sent a check for $100. At the entrance door of the Museum I will place a bronze plaque with the legend of the museum, the name Enrique Squirru and his portrait of him. "The local newspapers comment well on the initiative and this helps a lot because it creates a favorable environment."

In May 1944, he offered to the Popular Library, destined for the Museum, all the ethnographic and archaeological material that constituted his private collection, and the furniture in which it was displayed, which he had built himself in his carpentry workshop located in the garage of his house. On March 22, 1945, the deed of sale of the old building located at the intersection of San Martín and Alvear streets, acquired by popular subscription, was signed. Composed of two bodies, the first of them, which forms the aforementioned corner, is the oldest material construction in Azul as it dates back to 1856; The second was built to expand the previous one and adapt it to its destination, based on plans made by the architect Blas D'Hers [26].

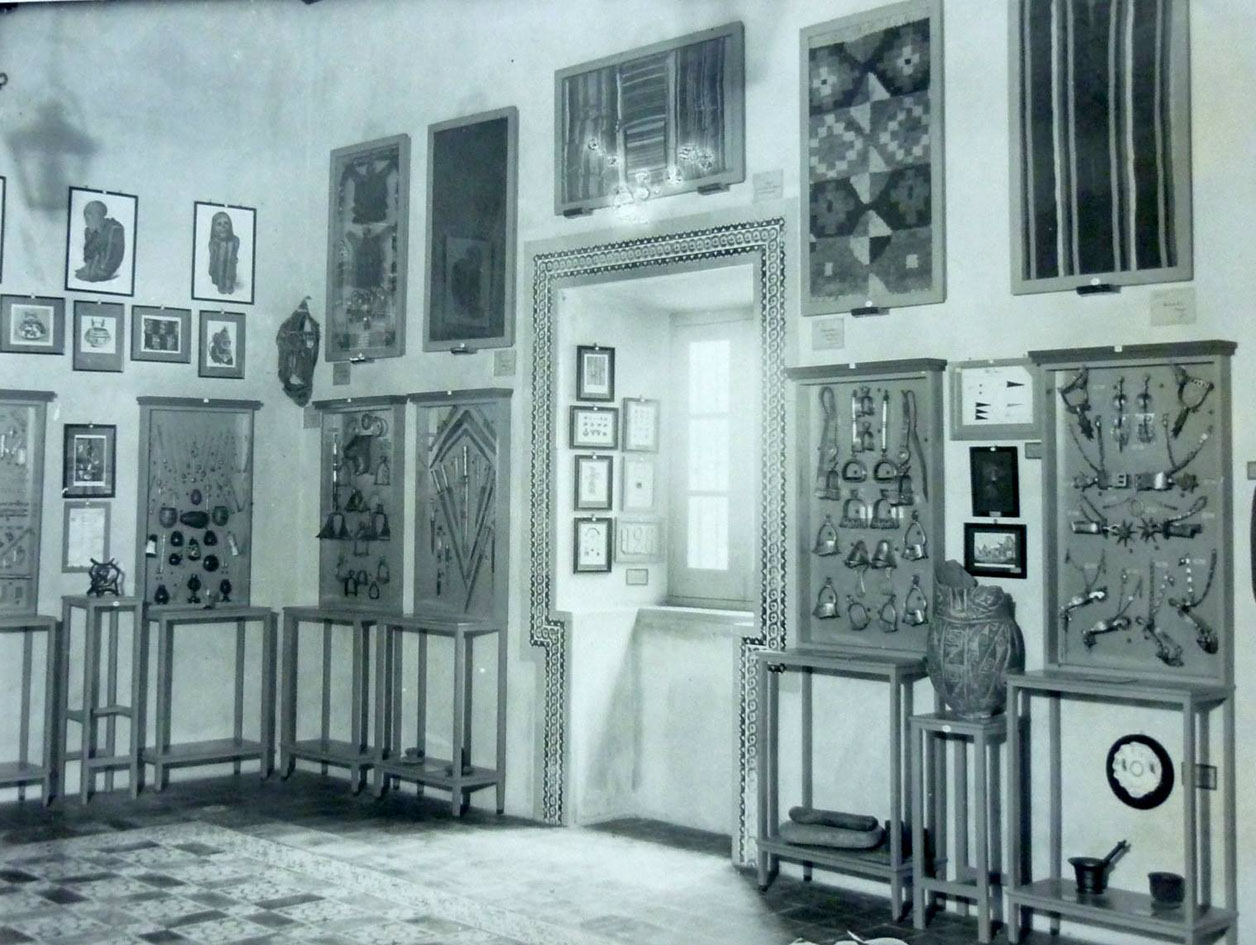

Crowning efforts, on April 8, 1945 the Ethnographic Museum, with its three rooms ("Martín Fierro", "José Hernández", and "Sargento Cruz") was opened to the public, an opportunity in which Ronco gave an emotional speech [27 ]. The Historical Archive includes thousands of documents related to the History of Azul, part of which were preserved in the archive of the local Peace Court; many of them from the time of Rosas and the State of Buenos Aires.

Pieces of Pampa silverware exhibited in a showcase at the Museum. Photography: Tato Soriano.

The Museum, which operated in its own premises, did not depend on the local Municipality or any official institution, nor was it subsidized by the Government of the Nation or the Government of the Province. It supported its budget with resources from the Popular Library.

Barely fifty days had passed since his death, and on June 24, 1952 his widow wrote to the Uruguayan Cervantist Arturo (that's what they call me), my books, my books!

Three years after his disappearance, his library was described as "specializing in gaucho literature, folklore and regional history corresponding to the city of Azul and its tributary area." It has very complete collections of editions of Martín Fierro and Don Quixote. He died very recently - on May 6, 1952 - the collection that was his property is in the possession of his wife, Mrs. Nieves Giménez, San Martín 362, Azul, province of Buenos Aires", and she was considered among the 80 of a private nature in Argentina [28].

In the letter to Domingo Buonocore from 1946 that I have previously cited, Ronco expressed during his lifetime his last will regarding the final destination of his books: to be able to obtain a new and larger building for the Popular Library of Azul (which despite his valiant efforts could not achieve) would donate all the study materials from his private library. This materialized only in 1984 when his widow died, and the testamentary legacy of his house and everything in it was known, which became part of the collections of the Popular Library of Azul «Dr. Bartolomé J. Ronco », currently preserved in his private house.

Notes

1. Guillermo Palombo, "Bartolomé J. Ronco and the Argentine Society of Writers (SADE)", in Pregón. Regional Evening Newspaper, no. 19,093, Azul, May 14, 2021, p. 5.

2. Bulletin of the National Commission of Museums and Historical Monuments, year X, no. 10, Buenos Aires, 1948, p. 437.

3. Guillermo Palombo, «Presence of Alfonso Dánvila, ambassador of Spain, at the exhibition “Cervantes” (Azul, 1932)», in Pregón. Regional Evening Newspaper, no. 18,978, Azul, November 30, 2020, pp. 4-5.

4. Guillermo Palombo, «Juan Benigar (the loner of Peñas Blancas) and Bartolomé J. Ronco. Synchronies and affinities", in Pregón. Regional Evening Newspaper, no. 18,985, Azul, December 10, 2020, pp. 4-5.

5. Guillermo Palombo: "Bartolomé Ronco, a volume with two collections of poems by Martí gifted to Estanislao Zeballos and the presence in Azul (1947) of the Cuban poet Nicolás Guillén", in Pregón. Regional Evening Newspaper, no. 18,080, Azul, November 12, 2016, pp. 6 and 7.

6. “Bartolomé J. Ronco. His funeral took place in Azul”, in La Nación, no. 29,026, Buenos Aires, Friday, May 6, 1952, sec. General information, p. 2, col. 6.

7. Guillermo Palombo, «A forgotten Azuleño jurist. Bartolomé J. Ronco (1881-1952) and the lawyers of his time », in Pregón. Regional Evening Newspaper, no. 18,281, Azul, August 29, 2017, pp. 5-9; and «Bartolomé J. Ronco, Tomás Jofré and the Criminal Procedure Code of 1915 for the province of Buenos Aires. The protection of the guarantees and effectiveness of the Criminal Process" in ibidem, no. 18,712, Azul, August 29, 2019, pp. 6-9.

8. Juan Ronco (In Memoriam). Tribute from the Cosmopolitan Society of Public Protection and Instruction. November 1925, Buenos Aires, Juan Ronco Library Editions, Volume 1, A. Pedemonte Printing Office, 1925, pp. 12-13.

9. "Cosmopolitan Society of Mutual Protection and Instruction", in La Prensa, year LXIV, no. 22,917, Buenos Aires, Thursday, November 24, 1932, 2nd. section, p. 2, illustrated with photographs.

10. Germán García, The Bernardino Rivadavia Popular Library. One hundred years of history. 1882-1982, Bahía Blanca, Bernardino Rivadavia Association, 1982, pp. 48 and 49.

11. Guillermo Palombo, "Bartolomé J. Ronco and his management at the head of the Popular Library of Azul (1930-1950)", in Pregón. Regional Evening Newspaper, no. 18,933, Azul, September 23, 2020, pp. 4-5.

12. Azul Popular Library and Horizontes Cultural Center, La Imprenta de Azul. Exhibition of books, brochures, loose sheets, drawings and posters printed in Azul from 1872 to August 31, 1948, Azul, s/e, 1948.

13. Ricardo Piccirilli, «Bartolomé J. Ronco. His work as a historian, philologist and bibliographer", in Bulletin of the National Academy of History, Vol. XXIII, Buenos Aires, 1949, sec. Tributes paid to members of the Academy. "Tribute to the corresponding academic Dr. Bartolomé J. Ronco, Celebrated in the city of Azul, on May 11, 1948", in ibidem, pp. [261]-275; “Speech by Dr. Bartolomé J, Ronco”, in ibidem pp. [276]-279. See also «A significant tribute was paid to Dr. Bartolomé. J. Ronco in the city of Azul", in Nativa, Year 25, no. 293, Buenos Aires, May 25, 1948, p. 25; and «Dr. Bartholomew. J. Ronco", in Nativa, Year 25, no. 300, December 31, 1948.

14. Guillermo Palombo, "Bartolomé J. Ronco and the Azul magazine (1930-1931)", in Pregón. Regional Afternoon Newspaper. Anniversary Supplement, Azul, October 2019, pp. 8-12.

15. Guillermo Palombo, "Bartolomé J. Ronco and Carlos G. Daws", in Pregón. Regional Evening Newspaper, no. 18,965, Azul, November 10, 2020, p. 4.

16. “Ethnographic Museum of Azul”, in La Prensa, no. 22,478, Buenos Aires, Thursday, September 10, 1931, section 2, p. 7.

17. Guillermo Palombo, «Silver jewelry and feminine ornaments used in the Pampa (Lelfunche) tribe of Catriel. Descriptive guide on the use of the Mapuche jewelry existing in the Ethnographic Museum of Azul”, in Special Supplement. History and concepts of Pampa Platería. August 2017. Pregón Supplement, Diario Regional de la Tarde, Azul, August 2017.

18. Popular Library of Azul, Ceramics Exhibition, Tribute to Reinaldo G. Marín. Catalog, Azul, Placente and Dupuy Printing Office, 1938.

19. Maná Artistic Group, Azul of yesteryear. Exhibition of paintings and drawings by Evaristo Giménez. Illustrated catalogue, Azul, Dupuy Printing Office, 1948.

20. Guillermo Palombo, "Bartolomé J. Ronco and the bookplates of his Library", in Fragments on the history of the founding of Azul, Special Supplement. 187th Anniversary of the Foundation of the city of Azul. December 2019. Pregón Supplement. Diario Regional de la Tarde, Azul, December 2019, pp. 5-7.

21. Guillermo Palombo, "Bartolomé J. Ronco, collecting and bibliophilia", in Pregón. Regional Evening Newspaper, no. 18,996, Azul, December 30, 2020, «Anniversary Supplement of the City of Azul, Azul December 2020, pp. 2-8.

22. Popular Library of Azul, «Martín Fierro Exhibition. Catalogue". Azul, Imprenta Placente y Dupuy, 1931. The complete and current cataloging of the collection in Alejandro E. Parada, Martín Fierro in Azul. Catalog of the Martinfierrista collection of Bartolomé J. Ronco, Buenos Aires, Academia Argentina de Letras, 2012 (Bibliographic Practices and Representations Series, vol. 6).

23. Popular Library of Azul, «Catalogue of the “Cervantes” Exhibition». Azul, Talleres Graphicos de Placente y Dupuy, 1932. The complete and current cataloging of the collection in María Mercedes Rodríguez Temperley, The cervantine collection of Bartolomé J. Ronco (Azul, Province of Buenos Aires, Argentina). Analytical-descriptive study and cataloguing, Buenos Aires, Universidad Nacional de Lomas de Zamora /IIBICRIT (SECRIT)-CONICET, 2021.

24. Guillermo Palombo, «Bartolomé J. Ronco: a Cervantista in the land of Martín Fierro. Don Quixote and democratic ideals» in El Tradicional, Buenos Aires, 2011, pp. 31-33; “Bartolomé J. Ronco and the Cervantists of his time”, in Pregón, Diario Regional de la Tarde, no. 17,434, Azul, November 5, 2014, Special Supplement Revaluing the spirit of Don Quixote, pp. 9-12; and "Bartolomé J. Ronco and his Cervantina Lexicogenia", in Pregón, Diario Regional de la Tarde, no. 18,533, Azul, October 24, 2018, p. 4.

25. Juan Sedó Peris-Mencheta, Contribution to the history of Cervantine and chivalry collecting. Speech read on March 14, 1948 at the public reception of Don (…) and the response of the permanent academic Don Martín de Riquer, Barcelona Academia de Buenas Letras de Barcelona, Talleres de la S. A. Horta de I. y E., 1948 , p. 103.

26. Guillermo Palombo, "The Ethnographic Museum and Historical Archive of Azul", in Pregón Diario Regional de la Tarde, no. 18,641, Azul, May 7, 2019, pp. 3 and 4; and «Presence of the neocolonial style in the building of the Ethnographic Museum of Azul, in Pregón, n. 19,076, Azul, May 18, 2021, pp. 4 and 5.

27. "The Ethnographic Museum and Historical Archive, Enrique Squirru, was inaugurated in Azul", in La Nación, no. 26,518, Buenos Aires, Sunday, April 15, 1945, 3rd. section, p. 2, engravings

28. Argentine Republic, Ministry of Education, General Directorate of Culture, Protective Commission of Popular Libraries, Guide to Argentine Libraries, vol. II, Buenos Aires, 1955, pp. 479 and 487. Copy from my library. The edition of this valuable guide in two thick volumes was never distributed because it was completely incinerated by order of the authorities that emerged from the Liberating Revolution, hence only a few copies are known, which for various reasons were withdrawn before the aforementioned destruction.

* Special for Hilario. Arts Letters Trades