The Italian critic Guido Ballo pointed out the existence of four eyes. The first of these was the so-called “common” and referred to the gaze of a certain casual audience that claims not to understand art, but defends a point of view that mistrusts critical discourse. The second was the so-called “snob” and alluded to the orecchiante subject, who “says by ear” from a superficial position that changes his argument according to the prevailing fashion. Third on his list was the “absolutist eye” whose owner, a controversial observer, always starts from a single visual angle for works from different cultures and from different times without paying attention to historiographical nuances. Finally, it was the “critical eye” that referred to a subject committed to a complex dialogue that always requires intuition, overcoming all preconceptions and willingness to change visual angles, in the plural, until finding the most appropriate one. Let's take the license to alter the order of Ballo's classification and then let's overlap his "critical eye" to the Third Eye convened by MALBA for the exhibition that it presents until January 2023 under the curatorship of María Emilia García.

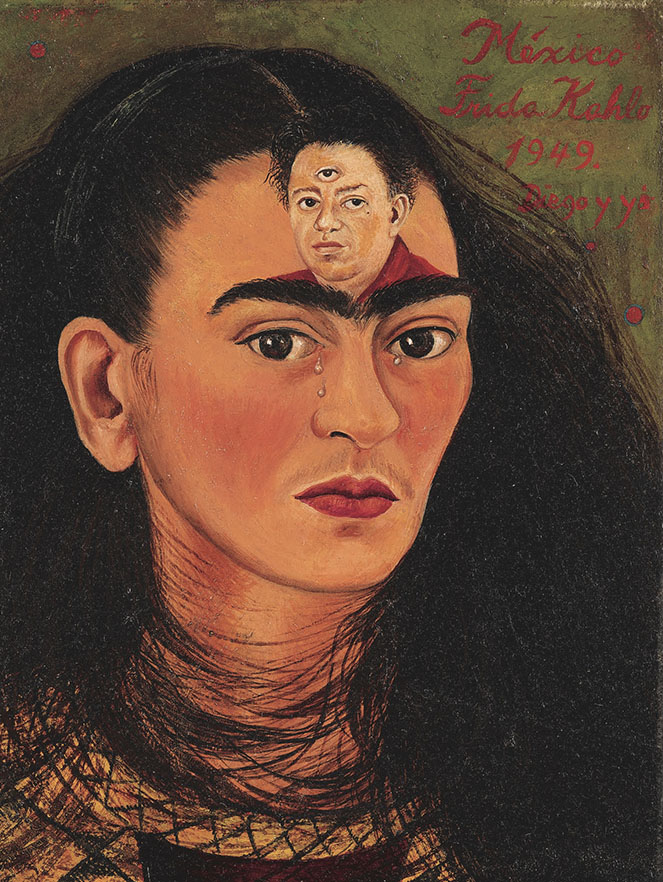

The viewer is invited from the beginning to a game of associations that begin (or end) with Diego and I. The last self-portrait painted by Frida Kahlo before her death in 1954, the oil is presented to the local public as a new acquisition that adds to the museum's heritage collection, and that introductory gesture launches (or culminates) the tour that opens to our look. In part memory that in its persistence allows her to retain the image of an elusive love, in part imagination that leads her to represent the unreality of someone who overcomes the human condition to position himself as an idol from whose gaze it is impossible to hide, and who also has a third eye from which it watches over a nonexistent intimacy, the protagonist's forehead undresses, opens like the lid of a metaphorical eye that looks straight ahead at the edges of the immeasurable: love and pain. It is that third mestizo eye that Kahlo put into action to paint the things of the world. Real, imaginary or unspeakable, everything fell under an observance that she did not hesitate to mix mimesis with surrealist accents that characterized a style exempt from epochal styling. And by programmatically mixing worlds and situations, Kahlo not only inhabited her life, but also transformed it into an extension of her work and, therefore, made it infinite, valid in her will to recover pre-civilizing motifs, practices and customs, in her vision of sexuality and in a spirituality that transcended the dogmatic.

Inhabiting and transforming are political gestures, life decisions that, within the framework of the exhibition, become conceptual nuclei that support the symbolic construction of Diego and I and exceed it to open the dialogue to a series of combinations more firmly sustained in thematic and formal drifts than in a historical period.

Xul Solar, Nana Watzin, 1923. Watercolor and gouache on paper mounted on cardboard. Measurements: 15 x 21 cm. Eduardo F. Costantini Collection. Photography: Malba.

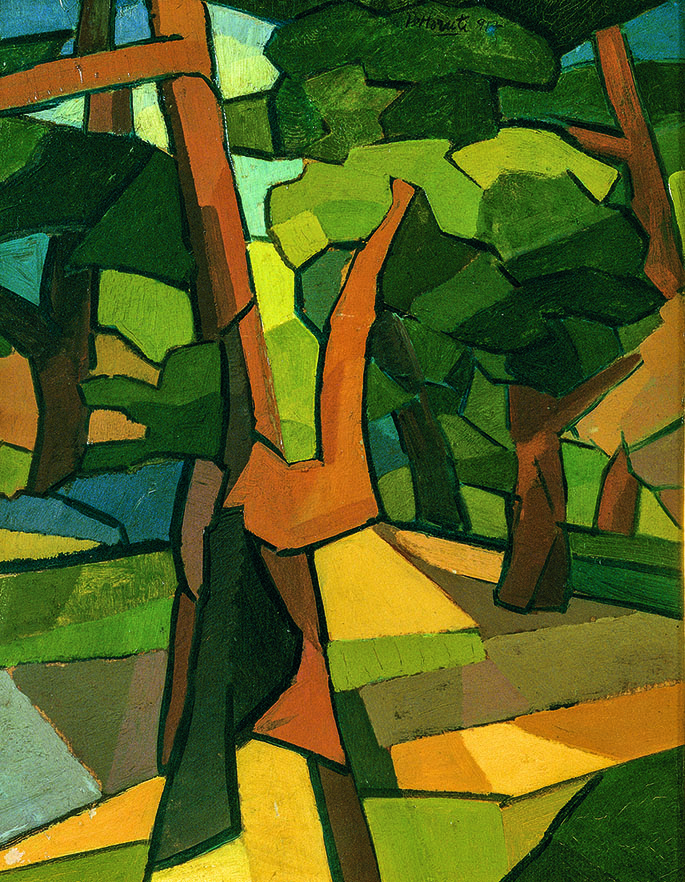

The earth is inhabited from works that, like Abaporu, signal a recovery of the primitive, from materials that evoke its colors, as in Angolo d'un Giardino by Emilio Pettoruti, from ritualistic evocations such as those of Xul Solar in Naná Watzin, from the characters of Leónidas Gambartes, or from the exhibition of the environmental crisis worked in the colorations of Nicolás García Uriburu, in the conceptualism of Víctor Grippo and in the performativity of Marta Minujín.

The city is inhabited, exposing its transformations and its stage condition both for the avant-garde that records the acceleration of its times, from Torres García to Miguel Covarrubias, and for those who portrayed its most hostile and melancholic side, such as Jorge de la Vega or Guillermo Kuitca.

The limit is inhabited, rethinking the formal elements to address subjective construction and modes of collective representation. Thus, Wrinkle, by Liliana Porter, offers a denotative metaphor of the passage of time in the body while operating as a conceptual game of its unfolding from the multiplicity of technical resources, and O Impossivel, by María Martins, presents a duet indefinable that is nonetheless effective in registering an embodied tension between seduction and barbarism.

Reality is transformed, making it permeable to surrealist utopias that altered logic through access to the unconscious, or more rational abstractionist projects that rethought the language of the work of art as a way to erect the concrete.

Pablo Suárez, Exclusion, 1999. Enamel and acrylic on epoxy putty, wood and metal. Measurements: 190 × 199.7 × 32.5 cm. Malba Collection. Photography: Malba.

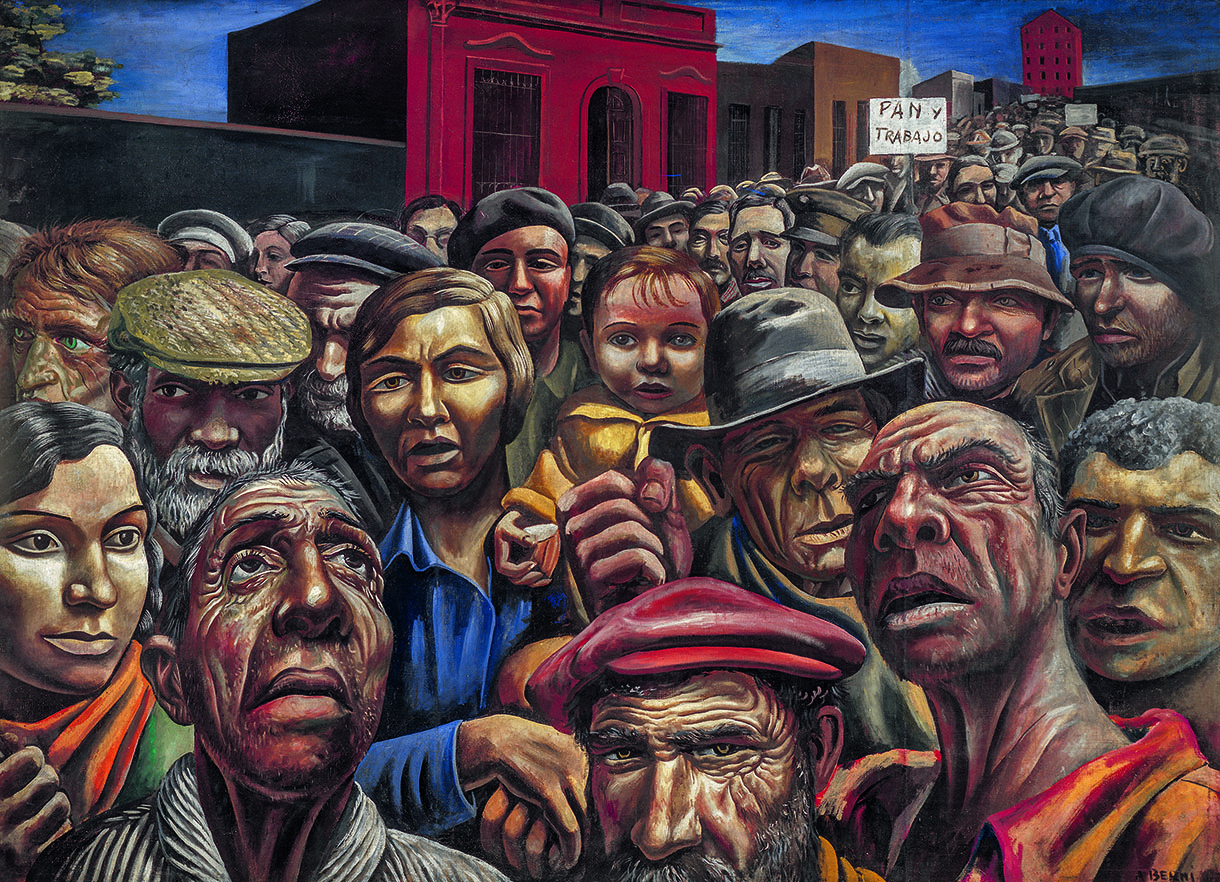

The social is transformed from a constant struggle for the realization of a full collective life from works that reflect on the fabric in conflict. In this space, the strong faces with elusive gazes in Antonio Berni's Demonstration enhance the disjointed rictus of Exclusion, by Pablo Suárez, whose protagonist fights from the margins to join a reality that violently expels him.

The body and the word are transformed, as they constitute expanding territories that signal the changes in the ideological configuration of the world.

The device is transformed to turn the work into a complex, ambiguous artifact, increasingly alien to a contemplative reception and more open to a spectator poiesis.

Life and death are transformed in that presentation module of Diego and I. But this last (or first) metamorphosis is a decision common to all the protagonists of the exhibition who chose to inhabit transforming, adding to the rational gaze that ineffable third eye that assists us intuitively and amplifies our sight to scrutinize, after the extension of what sensitive, the unspeakable possibility of connecting with the sublime.

* Special for Hilario. Arts Letters Crafts