Texts: Diego de Torres Bollo S.J. and Norberto Pablo Cirio. In 4th (20.5 x 15 cm), 146 pages. Paperback publisher's binding. Buenos Aires. Author's edition. 2023.

By Norberto Pablo Cirio *

Knowledge is a way to progress but it is also an instrument of oppression. Knowledge is power; Therefore, decolonizing power is a way in which, from the epistemic south in which we live, it allows us to understand certain passages in history and the present that have shaped us as we are or, rather, as we are not. If, for a long time, Argentina dreamed of being a biological and cultural detachment from Europe, it is true that it was at the cost of implementing an à la carte historiographical story, hiding the genocides that constituted the nation-state (the Chaco and Desert campaigns). and prior to it, the slavery of South Saharan Africans.

The metropolitan conquest was not only the work of the sword, but also of the cross and, with it, of the Word. Thus, with a capital letter, the bearers of the Truth imagined that the only path to salvation was faith in a God that they also imagined was unique. All the religious orders and the secular clergy agreed on this and, seeing the issue from a diachronic perspective, some peoples, such as the Mbyá-Guaraní, knew how to give a formidable lesson about the unconsummated “spiritual conquest” with which the Jesuits tried to overwhelm them by confining them. in reductions, since it was not voluntary but rather exercising power in an entirely chaotic and disorderly context such as the conquest by the sword. I think that too much ink has been spread praising the Jesuit capacity and ingenuity that not only sticks to the religious, but also to its civilizational approach towards the aborigines, even saving them from being annihilated. That is a voice of History but not everyone knows the other voices, those of the Others. Regarding the enslaved Africans, the attitude of the Church, in general, and that of the Jesuits, in particular, was even more cynical: they were so interested in saving their souls that they did not care that their bodies remained deprived of the greatest good that, the His own son of his god, he preached freedom with love.

“Slaves?, on the outside, on the inside more free than freedom and those birds”, This is a fragment of the poem The African, by the Afro-Argentine colonialist María Isabel Platero, who died a few years ago in La Plata, almost a centenarian. Thus, we recently began to have stories and artistic productions of the descendants of enslaved people in the country, a social subject that, it is never too much to remember, the academy and the hegemonic groups in power were in charge of already in the second half of the 19th century. to decree its extinction. A desk truth that today almost no one maintains, at least seriously.

Where are they, why can't they be seen, what happened to them? These are, among others, simple questions that almost any citizen and academic asks, not understanding that, rather than asking, it would be better to try to question the social mechanisms that They prevent us from seeing, since the understanding of reality does not come from the natural nature of vision, it is a construct that is taught in the family and at school. One way to make the gaze, and I add, the ear, fertilize this supposedly absent presence (the oxymoron is suggestive) is by listening to his version of the story which, as can be expected, is far removed from and more credible than the few lines. written about them, full of commonplaces, prejudices and futile comparisons with other countries where their presence and cultural weight is believed to be undeniable, Uruguay, Brazil, Cuba, etc.

What would it be like, then, a history of Argentine slavery? One way, among others, that I tried to plot it is this book, where I analyze a pamphlet printed in Lima anonymously in 1629 that has bilingual Catholic prayers, Spanish - “angola”. It was believed to be lost and it was not even known if it had ever been printed. It was known, frugally, that the first provincial of the Jesuit Province of Paraguay, Diego de Torres Bollo, presiding over it in Córdoba since 1607, had concocted it, using ladino blacks [that is, enslaved people with competence in Spanish and one or more African languages ] but nothing was known about his whereabouts. In this book I propose that he was the author of it, which he ordered to be printed having been transferred to Potosí [present-day Bolivia], to continue the propagation of his faith there.

Roberto Vega, owner of Hilario. Arts Letters Trades was the one who provided the first clue and for this reason it is one to whom I dedicate the book, because without it I could not have woven this story that, now, is presented as the oldest testimony of an African language spoken in what is today It is Argentina. This is Kimbundu, from the Bantu linguistic group, spoken in modern-day Angola. The reader may deduce from what has been said why this language appears in the booklet with the name of this country, formerly the kingdom of Ngola. I'm sorry to disappoint you, because that's not the answer. If it is true that the Jesuits were interested in learning the languages of the indigenous and African people for their mission, it is also worth saying that they were only interested in learning them for exclusive missionary purposes. Ergo, they were not interested in languages themselves as a linguist might be; for them this discipline was a means, not an end. Hence, using the Ladino blacks, they asked them to translate the sentences of interest, from which they deduced the basic rules of their grammar by comparison with their native metropolitan languages and Latin, forcing oral languages to alphabetic writing, with the well-known entanglements that this implies.

I do not speak Kimbundu, neither ancient nor modern, but I used some dictionaries and grammars to understand how these sentences were translated and, what is most suggestive to me as an anthropologist, I incorporated into the research the voices of two Afro-Porteño women who claim to speak the language of their ancestors. It was there, putting that booklet with its oral memory in counterpoint of centuries, that I understood that the so-called "language of Angola" was, let's say, a monstrosity, not only because by using more than one Ladino black they must have spoken various African languages, but because most of the terms of Catholic dogma, such as cross, Holy Trinity and Easter, as well as other general terms of Spanish, such as Sunday, do not allow translation. All in all, this questioning gave suggestive results on a small set of words that are still valid in Argentine Spanish, whether in lunfardo, gauchesca or already incorporated by the RAE: tata = father; marimba = beating; milonga = words. To this list I add perhaps the most important one: Zambi = God. This is something unusual among those Jesuits, so scrupulous about dogma as to condescend to translate God, like this, with a capital letter. Torres Bollo was aware of this when he expressed it in a brief text at the end of the booklet, where he gives some instructions on how to pronounce the Word in “Angola” and the purpose of its publication: “As for the name Zambi, God, it has been doubted, it means properly to the true God, or some idol of these people. It will not be difficult, if it seems, the doubt of consideration, to put our word God in place of Zambi.” Shortly before, he mentioned Buenos Aires, as a slave port where the aforementioned Prayers were destined for evangelical use... This positions our city as what it truly was, an exit point for Potosí silver using the bodies of the enslaved introduced as fuel. here, having Córdoba as a nodal distribution center to the north, via Tucumán, and to Chile, via Mendoza.

In addition to the interpellation that I carried out with the aforementioned Afroporteñas, two appendices complete the book: in the first I transcribe another printed text by Torres Bollo about his order's obsession with evangelizing infidels (regardless of their color), a mission that motivated him to concoct a method towards blacks given “their short capacity.” In the second I transcribe an unpublished document from my archive, the sale of an enslaved woman in La Paz in 1810, with the hope that it will interest other researchers and the Afro-Bolivian people.

“They believed that white people did not die. My grandmother told me that her grandmother told her that the white man was not going to die,” recalled one of the interviewees. In truth, those who never died are the Afroporteños, given their contemporaneity, their empowerment, the validity of their memory about their origin beyond the Ocean Sea or Kalunga Grande, the reason that their African roots were rooted in the colonial era of what is today the Argentina. This is what Carmen Jesús Cabot predicted, a descendant of those who were denied everything except oblivion, who died before 1928: “Not everyone is going to die, someone is going to be left to tell the tale.”

* Special for Hilario. Arts Letters Trades

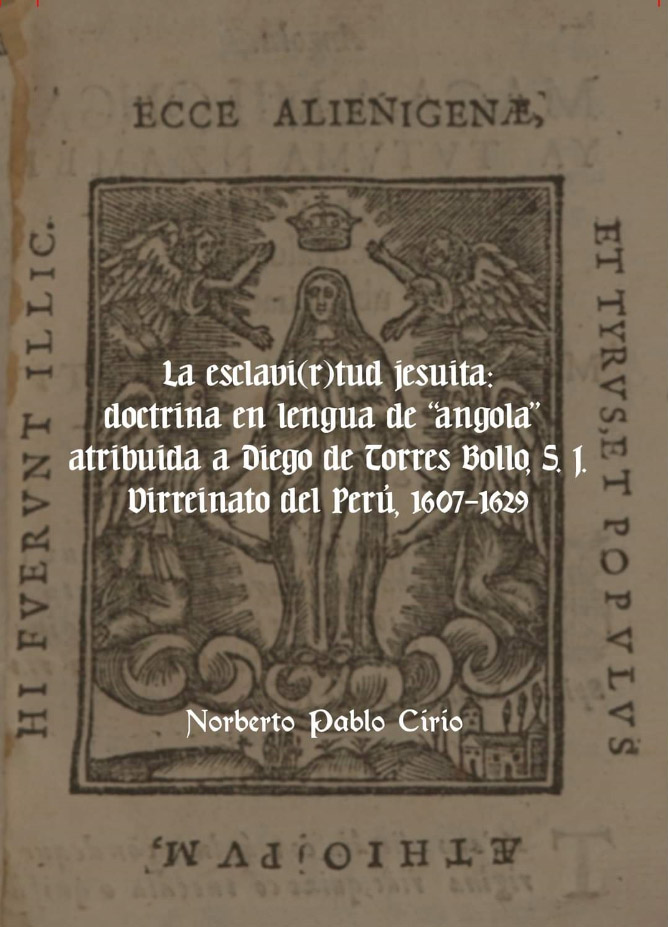

Cover of the pamphlet printed in Lima, from the copy kept at the University of Pennsylvania (USA), reproduced in the work of N. P. Cirio, La esclavi(r)tud jesuita: doctrina en idioma de “angola” attributed to Diego de Torres Bollo, S. J. Viceroyalty of Peru, 1607-1629.

The two-column texts present the Word on the left in Spanish and on the right in “Angola”.

Last page of the brochure with the indication of the year of publication, its printer and his place of residence.

To purchase, write to museoafroargentino@gmail.com // As of January 2024, its price in the physical version is Pesos 10,000 and in the e-book, 8,000.-