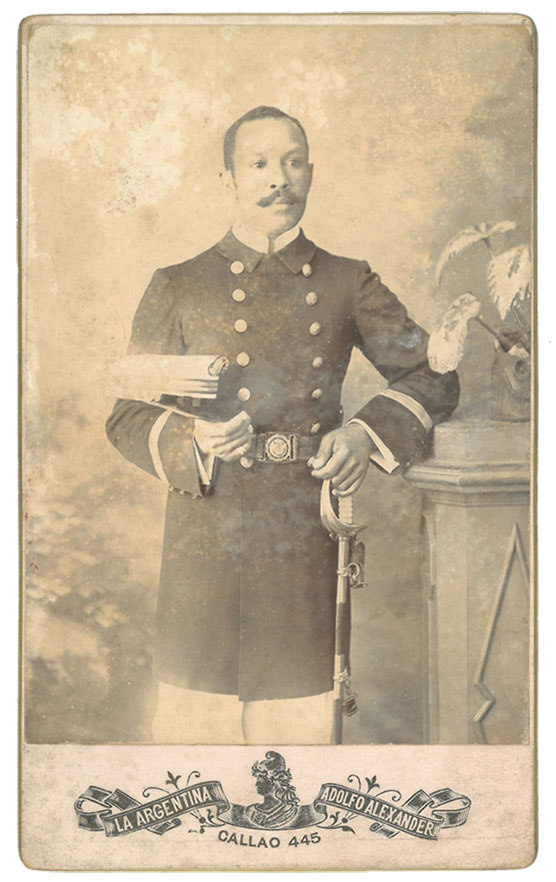

In 1899, the Afro-Argentine Jorge Miguel Ford published a book in La Plata in which he reviewed, with an elegant pen, fourteen men of what he believed to be the finest in his community, hence the title, Beneméritos de mi estirpe. Being a private edition and limited edition, it became a rarity and in 2002 the Ministry of Culture of the Nation reissued it, under the care of Eduardo Luis Duhalde, although without the portraits. At the beginning of the Prologue he says that he only knows three copies, one of his own, one from the National Library and another from an American university, so “Surely there must be some other copies in the hands of collectors and bibliophiles” (Duhalde: 2002: 9) . In 2010 the fourth appeared, given to Cirio by a man whose grandfather was a music student of Zenón Rolón, one of the biographers, to whom he dedicated it. The worthy ones are in chronological order and the last one, Eduardo Magee (Ford 1899: 123-126), is the one of interest here. In this article we expand her biography with previously unknown written sources and, most suggestively, the oral memory of her granddaughter, María Cristina Magee, who we interviewed in 2022 and 2023 and who treasures her belongings, for which we thank her for the kindness of providing us with her knowledge, accept that we write this text and its final reading.

The state of the art on him is scarce and is limited to the biographical genre. The first profile of him was during his lifetime, by Ford. We had to wait almost a century for another one (De Estrada 1979: 180-181), although it is brief and basically glosses the previous one. There are also mentions in macro studies about Afro-Argentines and some notes from the Argentine Navy, which do not provide anything new.

Eduardo was born in Buenos Aires on May 25, 1865 into a wealthy family, the fourth child (of nine) of the marriage of Edward Magee, a naturalized Argentine Englishman, and Luciana Pestaña, an Argentine. It is not known which of them, or perhaps both, were of African descent. Our hypothesis is that he does, understanding Magee as an ethnonym, for the Magí group, from the north of the Gulf of Guinea. During slavery there were some in Buenos Aires and they came to form the Mina Magí African Society, which operated at least from 1856 to 1860 (African Societies, Room X. 31-11-5). Ergo, Magee with a double e would be magí in English, a language in which to pronounce the i it is written this way. However, María Cristina remembers that he was not English but Irish and, due to the famine of 1845-1849, he emigrated to Liverpool and from there to Buenos Aires. Whether English or Irish, she understands that such ancestry influenced Eduardo, his brother and his father to work on the railway, which was then English property. On November 28, 1901, he married Carmen Zas in the Nuestra Señora de Balvanera Church and they had six children: Virginia Rosa (1902-1903), Eduardo Demetrio (1904-1972), Julio José (1906-1992), Jorge Calixto ( 1907-1926), Guillermo Rufino Mario (1910-19?) and Carlos (1911-1992), father of María Cristina in 1946, who remembered that the baptismal logic was the Catholic saints and, unlike the others, his father He only had one name because "My grandmother told my grandfather, 'Carlos, nothing more.'" He died on July 2, 1934 in Buenos Aires.

Within the framework of the rearmament that Argentina was carrying out due to the dispute with Chile, the government decided to commission the assembly of ships; one of them, the May 25 cruise. At the same time, the training of a corps of Navy machinists began and by Agreement of Ministers No. 2308 of July 4, 1890, a group of naval apprentices was sent to train in England since we did not have a school for this purpose. He was part of the Eduardo Magie (sic) contingent, which marked his entry into the Argentine Navy.

Entered Armstrong, Mitchell & Co. shipyard, Newcastle. During her stay there, the cruiser 25 de Mayo was built and in 1895 she launched the ARA Buenos Aires. In the English census of 1891 he appears in Elswick, Northumberland, sharing a tenancy with Robert Downie, also named in the aforementioned agreement, and with the Argentine and mechanic Loie V. Brignone. The demands of his instruction having been approved, at the end of 1891 he entered the workshops of Laird Brothers, Kirkenhead, Scotland, for three years, studying industrial mechanics. In Liverpool he studied mechanics and construction. In 1894-1895, having completed his studies, he completed the navigation requirement for 16 months on the ships of the Carlisle company of London, obtaining Certificate of Competence No. 30661 for the rank of Second Class Engineer of the Merchant Navy, issued by the Board of Trade on January 21, 1895. He returned on the transport Villarino and on March 12, 1895 he was discharged into the Argentine Navy, assigned to the cruiser ARA 25 de Mayo as a second-class engineer. These were his fate for 17 years until, on September 7, 1912, he retired.

Aug 12, 1895. ARA Villarino (transport).

Apr 1, 1896. ARA Bermejo (tanker).

September 19, 1896. ARA Uruguay (gunboat).

26-Oct-1896. ARA May 1st (transport).

Jan 1, 1897. ARA Golondrina (notice).

Nov 23, 1897. ARA Villarino (transport).

September 14, 1898. ARA Azopardo (transport).

Jan 10, 1899. ARA Gaviota (notice).

17-Feb-1900. ARA Maipú (transport).

September 20, 1900. ARA Pueyrredón (battleship).

Apr 5, 1902. ARA July 9 (cruise).

March 25, 1903. ARA Garibaldi (battleship).

3-Oct-1903. ARA Patria (cruise).

March 22, 1904. ARA Pampa (transport).

December 29, 1905. ARA Patria (cruise).

May 3, 1907. Merchant machinery examination commission.

December 18, 1907. ARA Pueyrredón (battleship).

June 11, 1908. ARA July 9 (cruise).

December 15, 1908. ARA Tehuelche (tugboat), to which he went on commission as a first class engineer, as chief engineer; From December 27 to January 25, 1809 he was part of the work to refloat the ARA Piedrabuena in Punta Loyola (Río Gallegos, Santa Cruz), with honorable mention.

20-Feb-1809. ARA National Guard (transport).

18-Sep-1809. ARA Almirante Brown (battleship).

4-Feb-1910. ARA Pueyrredón (battleship).

Self-portrait of Magee or portrait of Sebastián Zas (father of Carmen Saz, his father-in-law) and detail of his signature. Pencil on paper, 1901. Pablo Cirio Col.

In 2014 Cirio acquired a pencil portrait of a black man for his art gallery, signed “E. Magee.” Inquiring about his identity, he recalled that Afro-Porteño María Isabel Platero told him that it was the same Eduardo Magee, who was his godfather, so it would be his self-portrait. However, María Cristina assures that it is Sebastián Zas, Eduardo's father-in-law. We are not in a position to intervene in this due to the few known portraits of our protagonist and the nonexistence of any of Sebastián. Even so, the work shows that Eduardo Magee dedicated himself to drawing and, although Ford said that he was good at sculpture, his granddaughter never found one of them; yes with charcoal drawings.

Norberto Pablo Cirio, María Cristina Magee and Oscar Oliveira. Buenos Aires, February 28, 2023.

María Cristina graduated as an English translator (UBA) and has a doctorate in Modern Languages (USAL), already retired, she worked in the Honorable Chamber of Deputies of the Nation since 1973 and was attached to the Buenos Aires government. Within this framework she made several publications (Magee [2000], [2002], 2006, etc.). The last one transcends by untying a Gordian knot, the existence by law of black doormen in the National Congress, which circulates as an oral anecdote and in the press, with only one academic approach (Colabella 2012), of regular quality by, among other issues, ignore his article, for more fruit of his doctoral thesis on the terminological equivalence of the Argentine-North American parliamentary procedure, for which he had to delve into England, “the Mother of Parliaments”, from where the term goalkeeper was mistranslated and its responsibility.

Eduardo's Masonic membership was published by Alcibiades Lappas (1966: 269). In a brief mention he says “English by birth, naturalized Argentine”, which is inaccurate, as we explained. His status as a Freemason was unknown to his descendants until 2022 when Oliveira, researching in the Argentine Grand Lodge of Free and Accepted Masons, documented it. He was initiated on December 10, 1912 in the Daniel María Cazón Lodge No. 73, in Yerbal 777, Caballito neighborhood (which, in Masonic terminology is Valle de Caballito), reaching the rank of Master on August 1, 1913. In his Lodge he completed the cursus honorum, being Secretary, 1st Warden and Venerable. In the Scottish Rite he reached the 18th degree. He was delegated to the Assembly of the Grand Lodge, drafted its statutes and obtained legal status, presiding over it in 1921-1922. Being venerable, he formalized the headquarters of his lodge. If he retired on September 7, 1912 and on December 10 he was initiated as a Mason, it can be understood as the continuation of his military career, but we do not know what motivated him and who invited him. We also point out that he was related to Tomás Braulio Platero, the first Afro-Argentine public notary and Freemason, as well as with the Argentine Mutual Aid Association “La Protectora”, also of Afro-Argentines.

This article is the biography of an Afro-Argentine who lived through a complex period in the country in the face of its reinvention as a biocultural incarnation of what was considered the greatest of humanity, that is, the Western metropolises. In that project, the pre-existing alterities of the nation-state were not only condemned by the hegemonic groups in power as dysfunctional, but they also took over its past to erase it from Official History. A family like Magee, in whose house they conversed in English to the sound of White Horse whiskey, helps to understand how its members ascended socially on the metropolitan scale of values.

To transcend the biographical genre, we open a range of questions that, taking into account the dynamics of Afro-Argentines (from the colonial stock or, in this case, Afro-immigrants), contribute to hitherto untreated topics, such as Freemasonry. In this regard, Oliveira (2022) studied the belonging of the composer Cayetano Alberto Silva and, with Cirio, they have already identified seven. Another question is the implication of the enslaved and their descendants in the Argentine Navy and seafaring in general. As background we cite the anonymous person that Luis Vernet bought and took to Puerto Luis, in the Malvinas Islands, who, with two laborers, arrived in South Georgia in 1829 (Cirio 2018). This gives a twist to the concept of the Black Atlantic, by Paul Gilroy (2014) to account for the slave ship as a chronotope because it was where the enslaved began to forge a macro, sui generis identity. Magee sailed through that sea of memories chained under the flag of freedom, but his experience puts into perspective how the banished children of Africa continued to understand, as Afro-Argentines of Bantu descent say, the Kalunga Grande, a protective marine entity that in America was reconceptualized as Kalunga Chica. or cemetery, since it is estimated that 30% of the twelve million enslaved people died in the intermediate journey. This article also encourages research into the dynamic Anglophone Afro-Porteño community, which dates back to at least 1829 with emigrants from the United Kingdom, Barbados and the United States of America. It also reveals that the sense of aristocratic belonging that Freemasonry gave to Magee is an inadvertent nuance of the social rise of certain Afro-Argentines.

To conclude, if another lesson leaves this analysis, it is that in the area of Afro-Argentine studies it requires direct, fluid and continuous treatment with them. And it is not only about being able to access documents and knowledge, but it represents a qualitative leap in ethics by ceasing to refer to them as “objects of study”, a hindrance of a colonial academy that reproduces the most archaic of its founding notions, a continuation of the saga of the mistreatment of the enslaved as “living ebony” by traffickers, or “irrational rocks” by racists of the stature of Domingo Faustino Sarmiento (Cirio 2024) when he argued with them, in 1858, stunned by his diasporic consciousness when he titled his first newspaper La Raza Africana, that is, El Demócrata Negro.

Note:

1. Director and member of the Free Chair of Afro-Argentine and Afro-American Studies (UNLP).

* Special for Hilario. Arts Letters Trades

Sources

General Archive of the Nation. Room X. 31-11-5, African Societies, Leg. 32.

Archive of the Grand Lodge of Argentina of Free and Accepted Masons. Buenos Aires.

Archive of the Basilica of Our Lady of Mercy of Mount Calvary. Buenos Aires.

General Army Archive. Buenos Aires.

England and Wales Census, 1891, database with images, FamilySearch.

Jorje Miguel Ford, Beneméritos de mi estirpe: Esbozos sociales. La Plata: Tipografía de la Escuela de Artes y Oficios, 1899.

Alcibíades Lappas, La masonería argentina a través de sus hombres. Buenos Aires: Ed. Part. 2º Ed., 1966.

Bibliography

Norberto Pablo Cirio, Tras su manto de neblinas… Presencia de afroargentinos del tronco colonial en las Islas Malvinas en el siglo XIX. Actas de las VII Jornadas de Historia Regional de La Matanza. San Justo, Universidad Nacional de La Matanza, p. 54-83, 2018.

Sarmiento racista. A más de 150 años de autorizar el corso los afroporteños le quitan la máscara. Resonancias 52 (en prensa), 2024.

Laura Colabella, Los negros del Congreso: Nombre, filiación y honor en el reclutamiento a la burocracia del Estado argentino. Buenos Aires, Antropofagia, 2012.

Marcos De Estrada, Argentinos de origen africano. Buenos Aires: Eudeba, 1979.Eraclio Domínguez, Colección de leyes y decretos militares concernientes al ejército y armada de la República Argentina. Buenos Aires, Sud-americana de Billetes de Banco, 1913.

Paul Gilroy, [1993] Atlántico negro: Modernidad y doble conciencia. Madrid, Akal, 2014.

María Cristina Magee, [2000] Las comisiones permanentes del Congreso de los Estados Unidos de América. Revista de Derecho Parlamentario 13: 1-19.

2002 La consideración del presupuesto federal en el Congreso de los Estados Unidos de América. Revista de Derecho Parlamentario 15: 1-20.

2006 Procedimiento parlamentario: Estado de situación en la terminología del siglo XIX. Legislación Argentina 10: 1-21.

Oscar Oliveira, Los orígenes afromasónicos de la marcha San Lorenzo. ADN 407 3: 187-226, 2022.