Today it may seem almost anachronistic to speak of “women painters.” Already in the Italian Renaissance, Artemisia Gentileschi (1593 - 1654?) among others, proved to be as talented as Caravaggio himself. Her story was hard as was her path in the art world, exclusive only to men.

Over time, many women began to dabble in painting, first as a kind of entertainment such as music or literature. In the middle of the 19th century, the first woman who decided to dedicate herself professionally to the plastic arts appeared in France. This was inconceivable in manly thinking, but Berthe Marie Pauline Morisot (Bourges 1841-Paris 1895) developed an artistic career for more than three decades, exhibiting from the age of 23 at the Paris Salon.

Born into a family of the upper bourgeoisie, she was the third daughter of a couple dedicated to commerce and finance. Her sister Edma de ella (1839-1921) will be her first companion when her parents encouraged them to venture into music and painting, initiating them in 1857 in private drawing classes. Descendants of the great Rococo painter Jean Honoré Fragonard whom they admired, they began their first guidelines with the neoclassical painters Chocarne and Guichard, the latter requested by both, who advised them to make copies in the Louvre Museum and who contacted them with Camille Corot, the great landscaper of the Barbizon School. Her way of capturing reality through light and color had a notable influence on the Morisot sisters, introducing them to the “plein air” technique. Both worked with Corot at his house in Ville d'Avray during the summer of 1861.

Constable and Turner inspired the new concept of landscape that anticipated Impressionism, and photography revolutionized approaches by creating different spaces with previously unknown balances.

The sisters' first participation was in the Paris Salon of 1864, with two landscapes admitted, a rarity, unusual for female artists. Auguste Renoir was a member of the jury. None of them knew at that time that they would be traveling companions on the difficult path of the Impressionist Movement. Berthe presents her work “Study at the Water's Edge,” a figure reclining over a pond surrounded by lush, dark vegetation. Still preserving the neoclassical style in which she had been trained, a longer and more broken brushstroke can already be observed in her branches, which heralds a very loose graphics that will accompany her for the rest of her life.

From there, both would exhibit until 1869, the date on which Edma married the naval officer Adolphe Pontillon, which meant her withdrawal from her painting. Berthe considered marriage as a possibility, but she was also aware that she still had a strong bond with art and she continued to continually exhibit in different spaces.

One afternoon, while she was copying a scene from an immense painting by Rubens, Henri Fantin Latour introduced her to Edouard Manet. From this meeting, her life changes completely, both personally and artistically. Rivers of ink have flowed regarding this relationship, like that of so many others between masters and disciples. The truth is that Berthe became not only her favorite model (“Berthe Morisot, 1870, Musée d'Orsay) but also her most devoted and passionate disciple. This is one of the most successful portraits in the history of modern painting. The physical resemblance is admirable, but the achievement of having captured her expression, her physical features and even her temperament, turns this magical canvas of absolute black and white into a true gem. Morisot appears again in the foreground in her famous work “The Balcony” (1869), which generated controversial comments of all kinds, despite the fact that she attended all the modeling sessions with her mother.

Édouard Manet, The Balcony. 1869. Orsay Museum, Paris, France.

Her connection with Manet allowed her to be informed about the debates between modern art and everyday reality, which were discussed in the Guerbois café, a place forbidden for women. Ella Berthe organized weekly evenings at her family's home that allowed her to meet, among others, Edgar Degas, Charles Baudelaire and Alfred Stevens. This allowed him to bring her interests closer to those of the future Impressionist group, recreating domestic scenes and practicing plein air painting. A beautiful example of her is the work “Portrait of Mother and Daughter” (1869, National Gallery in Washington), where she represents her sister Edma pregnant with her, and her mother dressed in an intense blue-black. It was Manet who, taking his palette and its brushes, retouched almost all of the dark folds of the skirt without asking for any authorization, silently subordinating it to the attitude of a master as superb as he was brilliant.

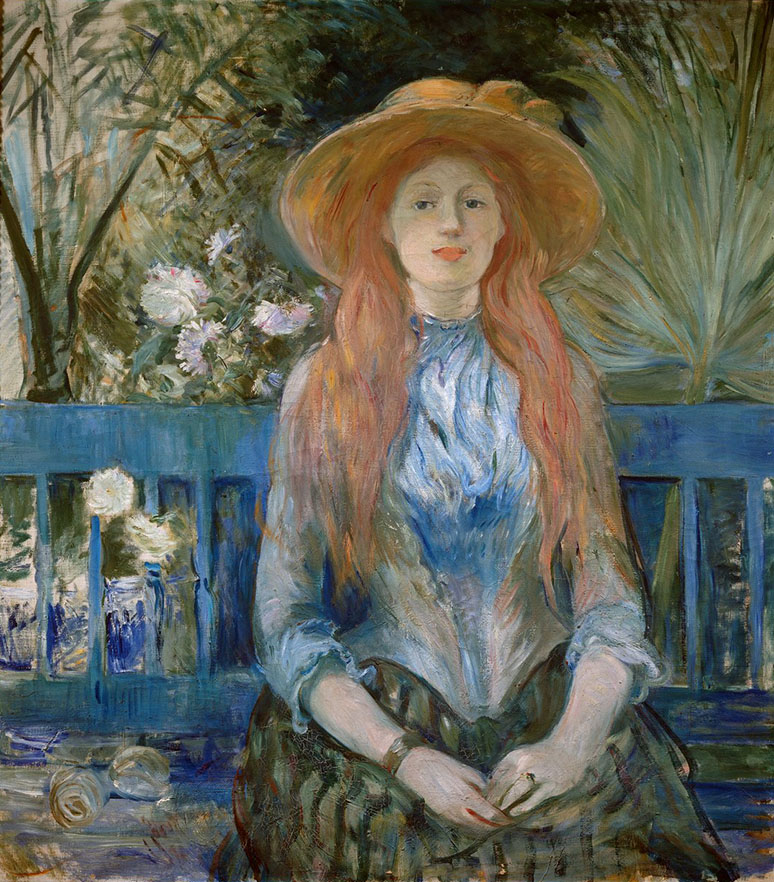

In 1870 the Franco-Prussian War broke out. Berthe and Manet are some of the few painters who remain in Paris. With the arrival of winter, Morisot's health suffered due to hunger and cold, so he decided to move to his parents' house in Saint Germain en Laye, and later he settled in Cherbourg where he reunited with his sister Edma and resumed the painting. It is at this moment where his style will clearly emerge. His palette illuminates, his long strokes become vibrant brushstrokes, the exterior atmosphere becomes transparent inside his scenes, and his compositions begin to be thought of in pinkish, greenish and bluish whites. Taking his sister and nephews as models, he painted his most emblematic works, “The Cradle” (1872, Orsay Museum, Paris) where Edma appears in a loving and thoughtful attitude with her little daughter Blanche, “Woman and Child Sitting on the meadow” (1871) and “On a bench” (1872). In these works, the influences received fade away, and the absolute economy of color appears, the atmospheres of feminine and domestic intimacies, and little by little the contours will be diluted to open the forms in very loose brushstrokes full of passion.

Berthe Morisot, The Cradle. 1872. Musée d'Orsay, Paris, France.

In 1872 he sold 22 works at the Paul Durand Ruel Gallery, which marks a milestone in his professional career not only because of the sales success but because for the first time an artist was able to overcome the barriers of genre.

With the end of the war, Morisot returned to Paris to continue his artistic career preparing the works that he would present at the Salon of 1873. An extremely conservative jury only accepted one of his pastels, also denying the presentation to Monet, Pissarro and Sisley. The discomfort caused to the artists led to the creation in December 1873 of the Joint Stock Society of Painters, Sculptors and Engravers, which was able to organize its first exhibition on April 15, 1874, in the former workshop of the photographer Nadar, where Berthe was the only female participant. She will continue exhibiting for twelve more years, except in 1879 when her only daughter Julie is born, and she posed many times for her mother and even for Renoir.

Like Mary Cassatt, Eva Gonzales, or Marie Bracquemond, Morisot was relegated to the background by art historians, including them all in the category of “female artists” for their themes linked to daily life and representations of society. privacy. She knew how to paint immediacy, what she had before her eyes, what was developing in her own environment or country sports, since the male world was forbidden to her.

In 1874 she married Eugene Manet, the brother of her teacher. He was an amateur painter closely linked to artistic and political circles that helped his wife a lot to fully develop her best professional moment. The following year they traveled to the Isle of Wight in the United Kingdom. During her stay there, contravening the rules of compositional balance, she begins to develop a new way of working, with short and quick brush strokes to represent both objects and people. She captured the movement and fall of light by drawing discontinuous and fast lines with the material distributed even with the tip of the brush. She practically leaves black to turn to a clear palette, full of nuances and glazes.

In the 1870s, she dedicated herself to the best female scenes. In “The Dressing Mirror” (1875, Thyssen Bornemisza Museum, Madrid), she displays all her sensuality and capture of the moment in her transparent whites; In “Young Woman in front of the Mirror” (Art Institute of Chicago) intimacy is treated with absolute respect without forgetting for a moment refinement and quality.

Berthe Morisot, Young woman in front of the mirror. 1875. Art Institute of Chicago, USA.

At the same time she will begin to develop her series of nudes using different techniques, such as pastel, watercolor, charcoal, and engravings.

Morisot exhibited in London and New York, achieving unsuspected success. And she was the first woman to exhibit individually at the Boussod and Valadon gallery in Paris in 1892. That same year her husband Eugene died. On March 2, 1895, as a result of pulmonary congestion, Berthe Morisot died at the age of fifty-four. Her remains rest in the Passy cemetery next to those of her husband and those of her brother-in-law Edouard Manet.

The Marmottan Museum in Paris houses 25 of her finest oil paintings, and 65 exquisite watercolors by her. The Orsay Museum preserves 10 high-quality oil paintings.

I believe that, although Morisot was absolutely linked and identified with the Impressionist Movement, participating in the friendship and principles of almost all its members, she was not exactly a painter who used the technical resources that characterized Monet, Renoir, Pissarro or Sisley where the human eye was the one that gathered the points of color and in this way recomposed the lights and shadows in an absolutely revolutionary way. Morisot was different. She developed a personal way of capturing the environment, quickly moving away from her beginnings in neoclassicism to create a painting of open forms thanks to her long broken and moving brush strokes.

This unique figure within the world of art, who knew how to encompass different facets in a world that was perplexed by Modernity, she never renounced being a woman for being an artist or being an artist for being a woman.

April 2024.

* Special for Hilario. Arts Letters Trades