For a personal interest, years ago we began the iconographic study of the city of Mendoza focused on the times before the earthquake that caused it to collapse in 1861. This search was driven by the passage through this capital of the German daguerreotype writer and photographer Adolfo Alexander -my great-great-grandfather-, who settled there in 1855 and five years later, already settled in Buenos Aires, publicized the sale of his views of Mendoza before the earthquake, images hitherto unknown.

Those notes were now taken up by the discovery of a lithographic view made by A. Torrecillas, without an execution date, with the image of the Plaza Mayor in the days prior to the collapse of the urban nucleus. The work, held by the Hilario Gallery, confronted us with these efforts in the footsteps of Alexander, now revitalized with new research.

The ancient city of Mendoza was the protagonist of one of the most serious natural catastrophes suffered in Argentine history. It happened on Wednesday, March 20, 1861, at 8:36 p.m. local time, when a phenomenal earthquake of magnitude 7.0 on the Richter scale was registered, the effects of which were terrible for the city and for its terrified inhabitants.

Being the most important populated center in the Cuyo region, Mendoza was founded by the Spanish conqueror Pedro Ruiz del Castillo in 1561 and just a year later, Juan Jufré moved it two or three shots from its original location. Paradoxes of destiny, its importance was affirmed in its privileged geographical situation, since it was the obligatory step towards Santiago de Chile.

Testimonies of the time tell how that Wednesday, the entire urban plant collapsed in successive seismic aftershocks, knocking down from the humble mud houses to the huge and solid religious temples, the Sotomayor Passage, the Cabildo and other outstanding buildings. Human losses reached at least half of its inhabitants, not counting the wounded. Those who did not perish crushed by the rubble, died burned by the uncontrollable fire -it lasted for four days- or drowned by the waters of the Tajamar that left its course. In addition, this misfortune was compounded by the looters' robbery and, consequently, the summary executions carried out by the forces of order.

Old images of Mendoza

The unfortunate news quickly reached the large urban centers such as Buenos Aires, Córdoba and Santa Fe. The main national and even international newspapers echoed that catastrophe that shook the entire Argentine society, which soon mobilized to help the victims.

That disappeared Mendoza tricentennial, already destroyed, had been represented in a very scarce iconography; only a few watercolors, drawings, engravings, or lithographs with their records raised from the late 18th century. Among the artists who documented it with their buildings and representations of popular types and customs, we mention Fernando Brambila, Felipe Bauzá, Peter Schmidtmayer, Edmont Bigot de la Touanne, Auguste Borget, Johann Moritz Rugendas, Cristian Anton Göring and León Pallière. (1)

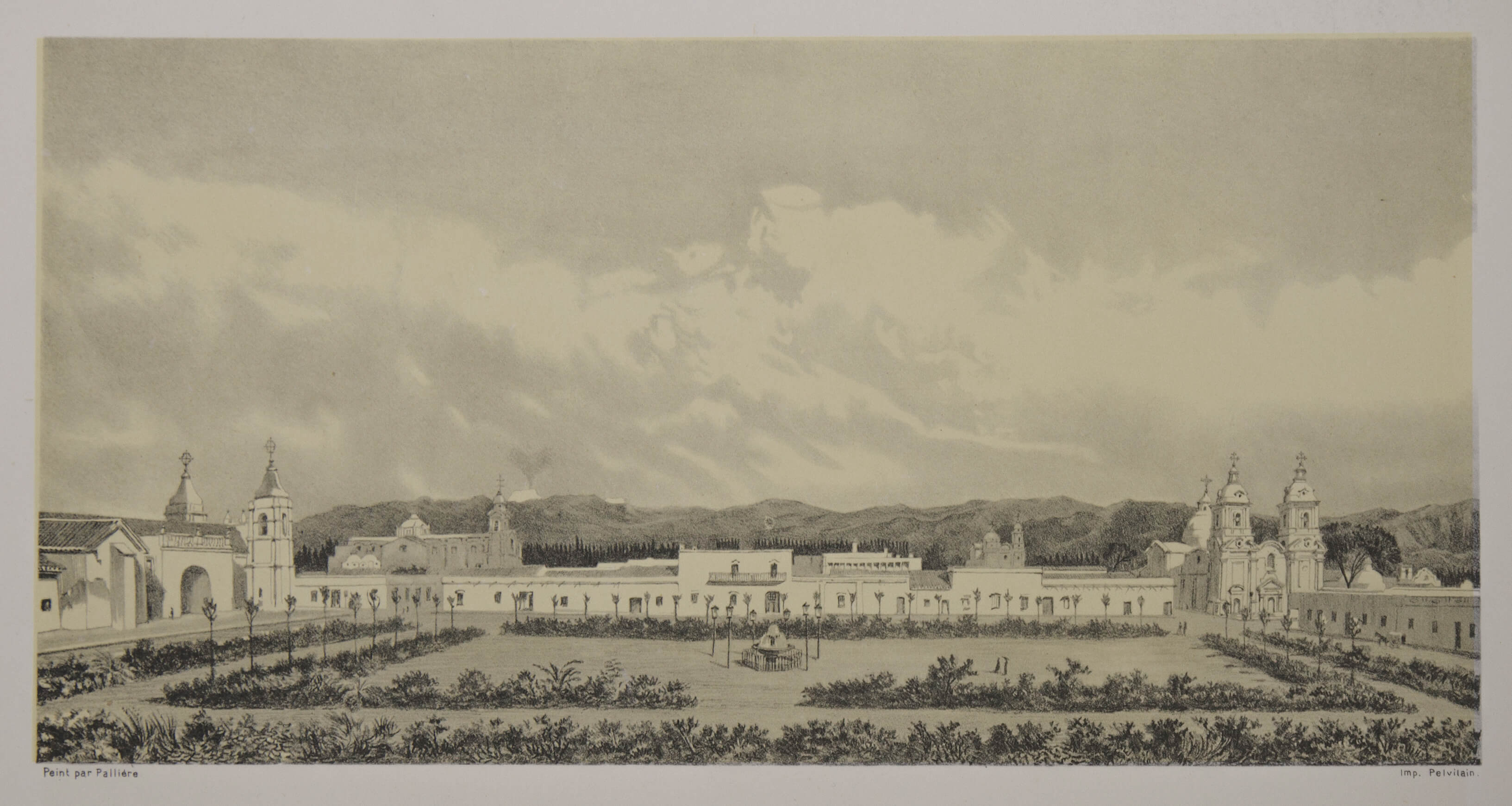

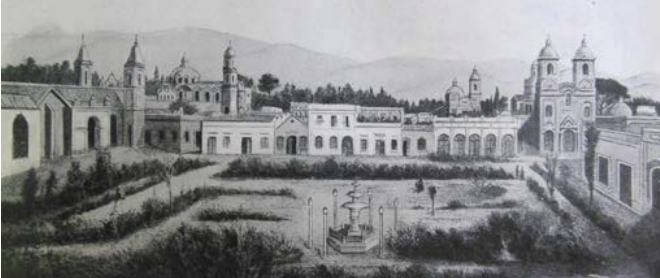

Among all of them, four views of the Plaza Mayor stand out, works considered fundamental in its iconography. We refer to the lithographic sheet made from the drawings by Juan León Pallière (1823 - 1887), the one included in Burmeister's album and two others signed by A. Torrecillas. The four panoramas on this nerve center of the old city were executed from above, with the perspective of the artist located on the first floor of the Cabildo and covering almost the entire tree-lined plaza, the central fountain with its illuminated columns and, left to right, the great Catholic churches such as the Matrix or Cathedral, San Agustín, Santo Domingo and the imposing temple of San Francisco.

Pallière visited Mendoza in 1858, on his way to Chile. In his Travel Diary he described it with little pleasure: “The main square does not look very ugly. In the center there is a fountain surrounded by newly planted trees, which one day will form a rather cheerful square. " (2) But if he highlighted the kindness of its inhabitants; "10 to 14,000 souls", he stated in his travel notes. Pallière stayed just a few days and continued on his way to Chile. A few years later, in 1861, his drawing of the Plaza Mayor illustrated a pamphlet entitled "The earthquake in Mendoza'', written by journalist Damián Hudson. Said plate published by A. Claireaux (Piedad 63, Buenos Aires) indicated in its lower margin: Drawing from life by Palliére (sic) and lit. by P. Mousee. (3) Finally, in 1864 the extraordinary Album of American Scenes was published, consisting of 52 lithographed plates in Buenos Aires by Jules Pelvilain, including his view of the Plaza Mayor, then known as Plaza Independencia.

Also in 1858 the German naturalist Carlos Burmeister arrived in Mendoza, where he stayed for about thirteen months, devoting special attention to his geological and geographical studies. Years later, between 1879 and 1886, he published his exceptional work Description physique de la République Argentine, contenant des vues pittoresques et des figures d`Histoire Naturelle (Buenos Aires, PE Coni 1881-1886. Paris, F. Savy. Halle, Ed Anton, en commission) with four volumes of text and two atlases, whose plates were stamped in different European cities. Among those relating to Mendoza, one bears the signature of Burmeister himself, another of Methfessel and another of Goering; the rest were published without indication of authorship, among these the view that interests us the most: "The Mendoza square before the earthquake of March 20, 1861." (4)

The painter Anton Goering or Göring (1836 - 1905), accompanied Burmeister on his travels through Uruguay and Argentina between 1856 and 1858, the year he returned to Germany.

One of Torrecillas's lithographs, whose title indicates “View of the city of Mendoza taken from the Cabildo in 1860”, has been specially used by different scholars, although none of them managed to date it, nor did they notice its great similarity with the lithographs from the original drawing by Pallière and published by A. Claireaux in 1861 and by Pelvilain in 1864. (5) This version of Torrecillas with the city prior to the earthquake, was executed -as it is indicated in the plate- when the artist and lithographer had his workshop on Salta 73 street, in the same city of Mendoza. The remainder -the one now exhibited by Hilario-, has a broader title and indicates another address, Rioja 70 -a figure that refers to a more or less prolonged stay-, in addition to presenting variations in its content; especially, in the perimeter buildings to the free space of the square.

Although we are before the author of the most reproduced preview of the earthquake in the 20th century, none of the researchers who illustrated their texts with this image managed to find a precise dating of it, although Cecilia Raffa argued in her study that it was raised before the earthquake, and that it is not a later recreation... "The drawing is made up of a succession of planes in which the square is located, with a double row of perimeter tamarinds and the central fountain enclosed and surrounded by some kerosene streetlights; the Matriz church, a succession of houses, a corner door shop (two streets away) and the San Francisco church (ex-Jesuits); the domes of San Agustín and Santo Domingo; the line of poplars that made up the Alameda and, as a backdrop, the profile of the Andes Mountains ”. (6)

Said panorama, signed by A. Torrecillas, was reproduced full page by Dr. Jorge Ricardo Ponte in his book “Mendoza, that city of clay” (7), where he alluded in detail to the impressions it had caused on Pallière and Burmeister, without adding more information about the lithographer A. Torrecillas, author of the published image. (8)

In 2012, CONICET researcher Silvia A. Cirvini attended the same hearing to illustrate her text published in the magazine Hispania Sacra: Religious orders in colonial urban space - Mendoza (Argentina). The case of the Society of Jesus. Referring to the foundational plaza as the center of community activity in the city, she illustrated this architectural space with this lithograph of Torrecillas. (9)

For C. Raffa, Torrecillas's work served as inspiration for the drawings published by Monsignor Verdaguer (10), "which show what we consider a colonial city with" imaginary "features". Raffa made his judgment based on the comparison between this sheet by Torrecillas (the one he printed with his lithographic workshop located in Salta 73, Mendoza) and the illustration included in Verdaguer's book; but he did not take care of the remaining view of A. Torrecillas -who added in his title that it was taken on March 15, 1861, and printed when his shop was at 70 Rioja Street, always in Mendoza. If we confront this panorama with the one edited in Verdaguer's work, we will see that the latter is a faithful copy of the former, although of a lower artistic quality, with cutouts on the side margins and the names of the churches located elsewhere on the plate.

In the idea of putting together a chronology of these lithographic views, we also consulted the study of the archaeologist Daniel Schavelzon referring to the earthquake, where he focused his gaze on the lithographs made from the drawings by Pallière and Goering -for Schavelzon, the panorama published in the album by Burmeister without indication of authorship, it is the work of Goering-, and again, without alluding to the elusive Torrecillas. (11)

Having made these observations, we still could not date the presence of Torrecillas in Mendoza. The new inquiries made in the various provincial archives looking for his stay at the time of the earthquake, contributed nothing. We only locate the mention in 1858 of a certain Ceccarelli, an active engraver in the capital of Mendoza, apparently the only one at that time. (12) So without other data, some questions remained: A. Torrecillas was contemporary to the earthquake, and the change of direction and of the lithographic plate between the two works known with his signature, was due to the destruction of his workshop due to the earthquake? Or, contrary to what Cecilia Raffa maintains, are we dealing with a later author?

But the research finally yielded its fruits and it was first among my old notes taken to carry out a study of the history of photography in Mendoza - on which I published an advance almost three decades ago (13) -, there I came across some annotations that they threw light on the enigma of A. Torrecillas: «In the Museum of the Founding Area of Mendoza there is a reproduction - unfortunately of very poor quality - taken from the Diario Los Andes (Mendoza) dated 4-1-1900. It is a graphic notice with the following caption: “Portraits in oil, pastel and pencil. Photography A. Torrecillas. Mendoza ”. The drawing that illustrates the advertisement brings together some classic elements of Fine Arts, such as the palette and brushes, and the initials "A.T." intertwined. " These were my annotations on that old note.

Reviewing these files, I also located him in 1901 as Antonio Torrecillas -he had publicized his business in the Commerce Guide of the Province of Mendoza-; Of course, this time with a piece of information that raised a new unknown: he appeared domiciled at Lavalle 175, in said capital city. With these references, we wonder if we were before the first steps of him here, or before the last ... And with the contribution of the researcher Rosario García de Ferraggi, we know that in the 1895 census no Torrecillas was located in the city of Mendoza. It was a first sign and the presumption was confirmed by the hand of a rigorous collaborator in that city, Víctor González Vásquez, who investigated the local archives and further specified the information available with new findings that enrich this article. Among them, the oldest reference, published in the Guide published by Flavio Pérez in 1898; on page 181, it reads: Torrecilla Antonio, lithography workshop, Salta 73. There was the address that the lithographer placed under his sight, and the dating was unappealable: 1898. Three years later, we indicated, he had moved to Lavalle 175, where it was also documented in the 1903 and 1904 guides. Without a doubt, a little later it moved again, now to 70 Rioja street, as published in the second engraving that came out of its lithographic house.

With all these references, we are in a position to affirm that he was not an artist contemporary to the catastrophe, but rather an author who, attentive to the demand for images of the city prior to the 1861 earthquake, was able to produce two beautiful views panoramic views, which surely aroused in the local public the same enthusiasm that summoned researchers from Mendoza decades later.

The photographic views

We do not want to close this work without mentioning the fact that the city of Mendoza was also documented in precise photographs before the 1861 earthquake. The task was carried out by the German daguerreotypist Adolfo Alexander (Hamburg 1822 - Buenos Aires 1881), the first professional to be settled in that capital from the year 1855 has expressly requested the minister of provincial government Don Federico Mazza by letter that is in our possession, dated January 26, 1856. This documentary task was later confirmed when Alexander himself - already established in Calle Artes 37, today Carlos Pellegrini, in Buenos Aires from 1860 on, offered for sale to the Buenos Aires public those beautiful views of Mendoza shortly after the great earthquake, indicating in a prominent press notice; "Views of Mendoza taken from various points one and two years before the earthquake". Unfortunately, and despite the intense search that we have carried out for many decades, these historic photographs - the only ones that record an Argentine capital that we never knew - have not appeared until the present.

After the accident and in the middle of the 19th century, several cameras recorded those impressive ruins, leaving us images that still move today, among which we can mention the albumen business cards or "carte-de-visite" made by the firm Helsby y Cía de Chile, the professional records of Benito P. Cerrutti, a photographer already established in Mendoza, or the widely publicized views of the talented Christiano Junior, who visited the city around 1880.

It should be noted as a remarkable coincidence that the photographer Adolfo Alexander maintained a close friendship with the German naturalist and scholar Karl Hermann Konrad Burmeister (1807-1892) when he was based for a time in Mendoza on a scientific mission; in fact, Burmeister was the baptismal godfather of his first-born son Adolfo Gerónimo Ramón Alexander (1857-1931). And taking this relationship into account, we do not rule out that the lithograph on the Plaza Mayor included in his album and edited by the renowned W. Loeillot printing house in Berlin, could have as a perfect model one of the photographic views executed by Adolfo Alexander, obviously, also obtained from the first floor of the Cabildo.

Notes:

1. This is how Bonifacio del Carril enumerates them in his Monumenta Iconographica (Buenos Aires. Emecé Editores. 1964), where he includes Giast, an artist who, according to recent studies, has been determined never to exist; his paintings were the fruit of an unscrupulous Paris-based merchant, Robert Heymann, who "commissioned" them for the consumption of South American collectors.

2. León Pallière: Travel diary through South America. Buenos Aires, Ediciones Peuser, 1945, p. 128.

3. A copy of it is kept in the General San Martín Historical Museum - Asociación de Damas Pro Glorias Mendocinas, (Earthquake 1861 Room), in the city of Mendoza.

4. The work of Germán Burmeister was printed in Paris, by commission of the publishing house of Buenos Aires, PE Coni, between the years 1881 and 1886. In its first part we find the Picturesque Views, gathered in XVI plates in large real folio, with thirty-six engravings of fine execution. In the Second Section of this work the world of Mammals of Argentina was addressed. To illustrate his Atlas, Burmeister made use of the originals executed by him and those erected by Adolfo Methfessel –by then his assistant at the Museum of Natural History in Buenos Aires–, A. Goring and W. Loeillot.

5. For the art historian Roberto Amigo, Torrecillas is based on Palliere's lithography.

6. Cecilia Raffa: Foundational places. Mendoza's public space, between technique and politics 1910 - 1943. Mendoza, Digital archive and online download, 2016, p. 66.

7. Jorge Ricardo Ponte: Mendoza, that city of clay. Municipality of the City of Mendoza, 1987, p. 147.

8. He also made a version of the same A. Davighi, dated (19)67, stating: taken from a photograph.

9. Silvia A. Cirvini: The religious orders in the colonial urban space - Mendoza (Argentina). In Hispania Sacra, LXIV, 130, July-December 2012.

10. Priest. José A. Verdaguer: Ecclesiastical History of Cuyo. Milano. Premiata Scuola Tipografica Salesiana. 1932.

11. Daniel Schávelzon: History of an earthquake: Mendoza 1861. Buenos Aires. Editorial of the Four Winds. 2007. And by the same author: Mendoza before the earthquake: art, copy or forgery? In Diario Uno. Mendoza, March 13, 2011.

12. We are grateful to Víctor González for the research carried out in the Library of the Board of Historical Studies of Mendoza, in the Provincial Historical Archive, and in the San Martín General Public Library. Among the newspapers consulted, he viewed the notices published in El Constitucional, in 1858, by Adolfo Alexander and Blas Velatti.

13. Alexander, Abel: History of Photography in Mendoza. Daguerreotype stage. In Proceedings of the 1st Congress on the History of Photography. Florida. Vicente López party. 1992.