Buenos Aires saw him born in 1896, when the pictorial profession still acted as the almost absolute ruler of turn-of-the-century aesthetics.

His academic training and submission to the National Salon in 1925 opened the doors to Europe, and first Renaissance Italy and later André Lhote's workshop in Paris were the guiding threads that would lead him to become one of the first painters. modern 20th century.

He will return to the country after having intensely experienced the European climate between the wars, equipped with a rich baggage of new proposals, and having developed to the maximum his capacity for learning and observing the new reality.

An excellent draftsman, a highly refined engraver and one of the few true muralist talents in our country, Spilimbergo builds his figures and his landscapes, avoiding any decorative or anecdotal resources, to transform them into essential, absolutely universal works. We perceive in his painting a controlled monumentality that is associated with permanent synthesis, a perfect example of the total handling of drawing, the fundamental support of the entire underlying structure in his work.

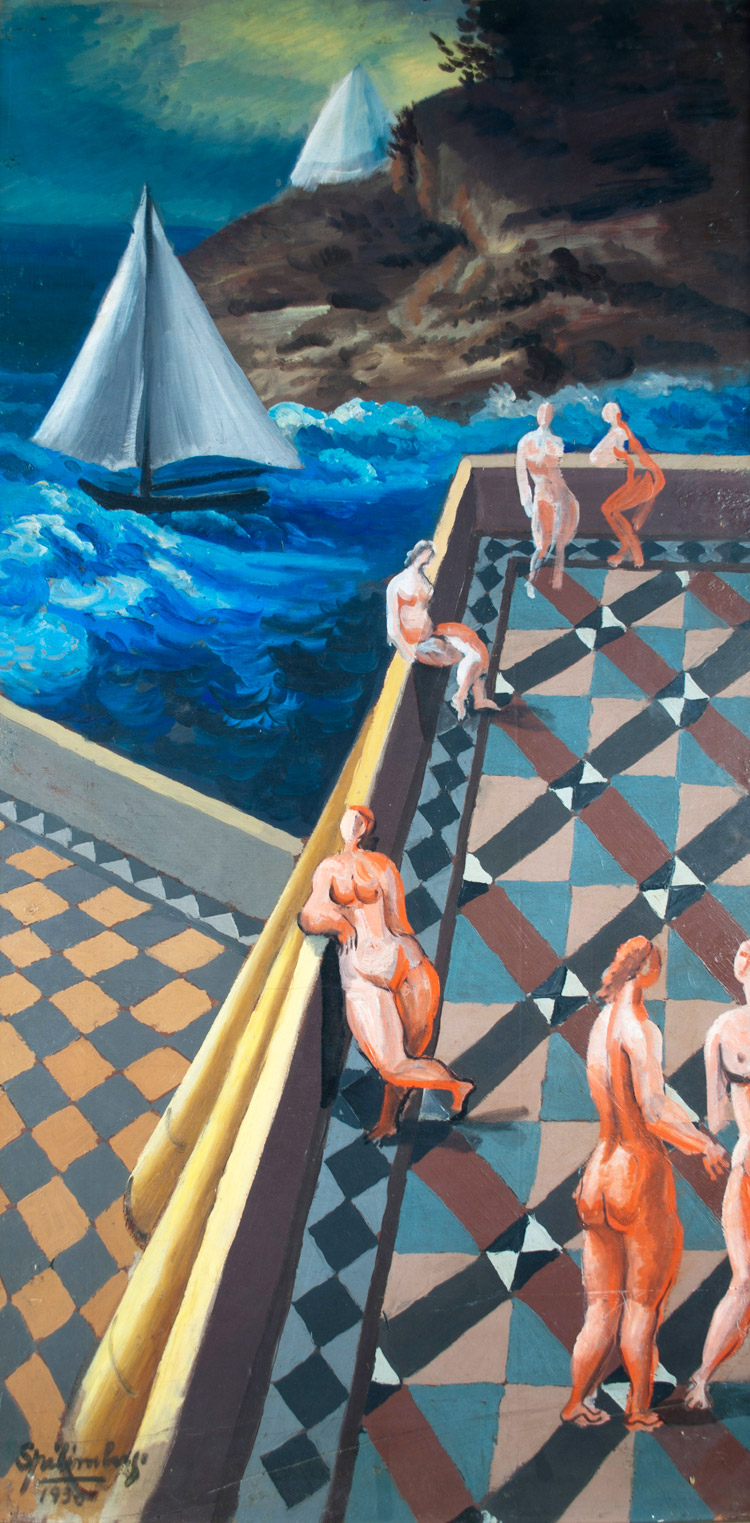

The series of terraces, which he painted at the beginning of the 1930s, impact us with their almost frozen images, and are located in a setting that removes all temporal reality from them.

Lino Enea Spilimbergo, Terracita, 1933, National Museum of Fine Arts. Photography: Courtesy MNBA.

The portraits, with a solid figurative concession, emerge accompanied by a very personal color, a deep content, and a pictorial material of great beauty.

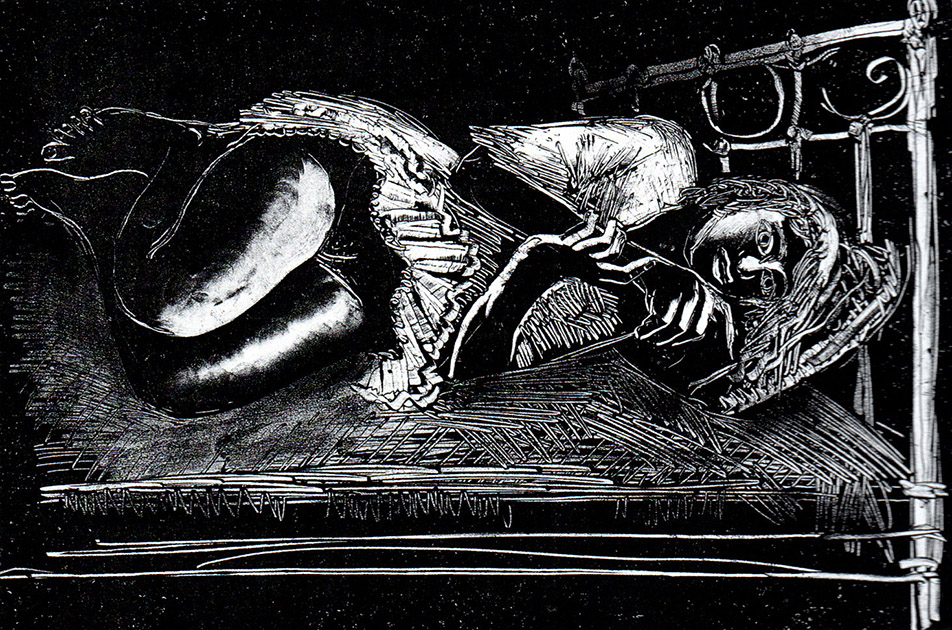

The monocopies made from the 1920s until the 1940s include time in the images. The figures are in movement, they expose vital situations, and above all they participate in a novel and dramatic story at the same time.

Brief history of Emma I. 47 x 27.5 cm., 1935. This monocopy is the cover of the series. Photography: Reproduced in the work “Spilimbergo”, Buenos Aires, National Fund of the Arts, 1999, p. 172.

Almost forty years after the scandalous presentation of Eduardo Sívori's work “The Awakening of the Maid”, Spilimbergo takes up the history of a rare theme at that time with the creation of the series of monocopies entitled “Brief History of the Life of Emma” that she made during the years 1936 and 1937, referring to the life of a woman with an absolute lack of future who will end up practicing prostitution and everything will finally lead her to suicide. The thirty-four monocopies that make up this magnificent set, which is complete in the collection of the artist's family, are based on an alleged police chronicle: “Emma Scarpini, 30 years old, authorized to practice prostitution, committed suicide by jumping on the ninth floor of a hotel. Known under the pseudonym “Lola,” her body has never been claimed. A letter addressed to her parents was found in her room in which she mentioned that she was not guilty and that she had always been good. There is no certainty about her true existence and Spilimbergo reconstructs the avatars of a girl who worked in an ironing workshop and at the age of seventeen she is invited to get into a car whose destination would be a brothel in San Fernando.

Emma, with short hair with a bun and big eyes, is an almost schematic drawing that will gradually transform and that describes anguish, resignation and death in the small space of a room whose objects, a simple bed, the jug and the basin accompany their existence reduced to total slavery. In a way, Spilimbergo denounces this exploitation through the dramatic story of her life and that of her companions. They contemplate each other, they show themselves without shame. Only in one scene does she appear with a man. In the subsequent sequences she is seen with her face worn out, covering it, curled up, until reaching the final work with a face that foreshadows her end. The work done entirely in black and white gives the series a greater dramatic charge. Spilimbergo masterfully handled the monocopy technique, creating unique pieces that reveal images full of sadness with their somewhat unfinished spaces.

Brief history of Emma X. 47 x 27.5 cm., 1935. Photograph: Reproduced in the book “Spilimbergo”, Buenos Aires, National Fund of the Arts, 1999, p. 179.

The artist's commitment to social issues is absolutely evident, and even more so to situations where marginality, extreme misery and lack of work seem almost natural, becoming an almost obligatory punishment that many immigrants suffered. It is clear that Emma, because of her surname Scarpini, was imagined by Spilimbergo as some of the sad results of the migratory currents that populated Buenos Aires at the beginning of the 20th century, seeking a better future.

While Spilimbergo draws Emma, economic crises break out worldwide. Roberto Arlt publishes “The Rabioso Toy” and “The Crazy Seven” stories where marginal or extravagant typologies are established, Buenos Aires characters marked by betrayal or failure as is also the case in Emma.

She integrates two aspects of Spilimbergo's militant figure: the aesthetic and the political. This story was told to challenge bourgeois society, which supported the drafting of laws that regularized and naturalized prostitution. When the exhibition of this almost symbolic character was exhibited in 1949 in Tucumán, it suffered censorship from the Church.

Brief history of Emma XIX. 47 x 27.5 cm., 1935. Photograph: Reproduced in the work “Spilimbergo”, Buenos Aires, National Fund of the Arts, 1999, p. 185.

“Ramona's Dream” by Antonio Berni (1976), one of the works that the artist dedicates to the protagonist of the Ramona Montiel series, seems to announce the closing of a cycle of Buenos Aires art that Sívori had opened with his “Awakening of the maid". With great knowledge of the facts, Berni uses basically the same elements that Sívori and Spilimbergo use for the scene: a room without visible doors or windows, a bed, a female body displayed in almost total nudity. Only now the maid has been replaced by an Emma sentenced to a fatal fate and a “light-living” Ramona who has no qualms about offering her body to the market of an increasingly perverse consumer society.

The eternal purity of the Renaissance line that flows from her indubitable mastery makes her art exude delicacy and vigor at the same time. Spilimbergo knew how to understand and assimilate the new trends, both cubist and metaphysical, that come together in an absolutely humanist work. All this architectural and pictorial scaffolding flows at the same time, with total naturalness. With the virtue that only those who have the talent to transcend time through creative genius possess.

* January 2024. Special for Hilario.