It was a rainy and foggy day, one of those Buenos Aires winters that we don't like to walk down the street. Someone, I don't remember her name [excuse me, ma'am!] She called me because she wanted to donate to some institution a series of letters and papers from her family that she didn't quite understand what they were. It wasn't a last name that reminded me of anything, to the point that I forgot it, and in a modest apartment in the Belgrano neighborhood where she was moving, she gave me a crumpled envelope with several letters inside. I promised to look at what she was and see what could be done, she had no idea if that had value beyond the family memory that she wanted to get rid of, or where to send them so they wouldn't get lost, contradictorily. What I saw were papers and that I was soaked and I would surely end the day with old letters and pneumonia.

I forgot her name over time, I'm sorry, but I can tell you that her letters went to the National Library a few years ago, as a peculiar and more than interesting set of letters. Lady: together with Patricia Frazzi we fulfilled her request.

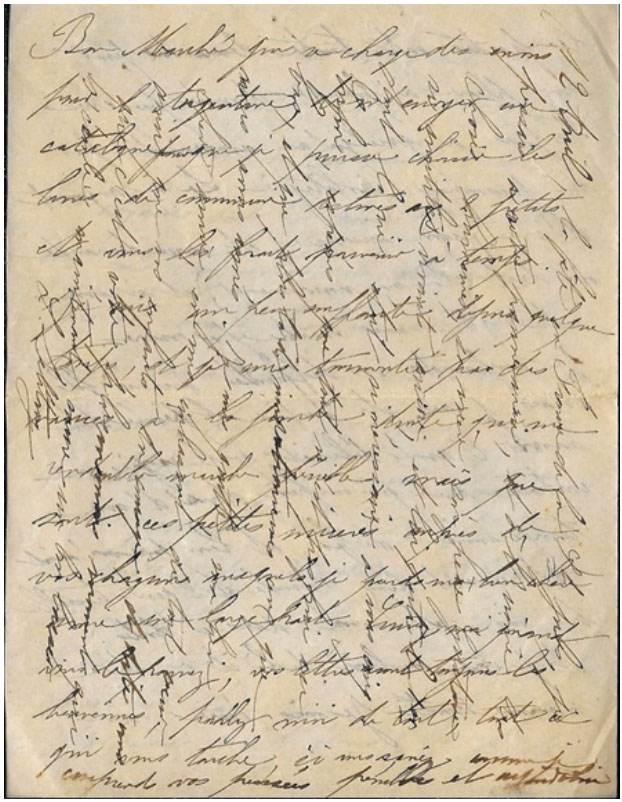

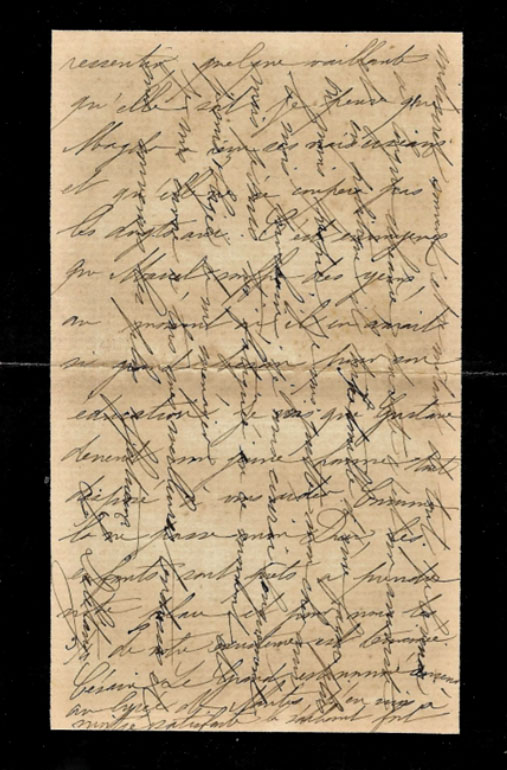

When I opened the letters I was stupefied, perhaps due to my ignorance that it could be written in another way than the one we are used to and with our Latin words (even if they were in French). Later I discovered that although it was unusual, it had not been so strange - there are others in the National Archive - but that was later and it was no longer raining and there was Internet. At that moment I could hardly understand a word of what was written with a precise but very complex handwriting: I only understood that most of it related to the Dubedou family, who lived in various places in La Pampa and the province of Buenos Aires since shortly before the end of the 19th century; The letters talk about the family and their problems with droughts and the land. They were immigrants who arrived from the small town of Bretoncelles, in Normandy, around 1890. A beautiful French town that even today does not have much more than a thousand inhabitants. It is possible to imagine that their new destination, although it was hostile and they moved several times, was an alternative to the misery and wars of their time. It would seem that in his lineage there were civil and military personalities, even a middle-class nobleman, but his situation must have been the same as that of the majority of those who emigrated. And these well-worded, difficult-to-read letters indicate a high level of education.

Already at the beginning of the 20th century there was a not very common practice of writing letters with what was called cross writing. That is, it is written in lines in a normal way, although trying to use all the paper to its last corner, and then write on top at 90 degrees. That is, the lines intersect each other and, at least in the first instance, reading is very complex.

When I looked at the cards for the first time, I had numerous questions: Was it a strange code? Were they secrets? Were they all crazy? Wasn't it simpler to write in simple lines? No, they were written that way because at that time letters were paid according to their weight and that happens to this day; although the fax made mail ineffective and the Internet ended up displacing it. What this case shows is that the family took care of every penny in this way, perhaps an expression of their problems and that international postal values were expensive.

The reading-writing method implied a very special ability for those who could use it. For the writer, the system was only possible to be used, at least efficiently, with metal pens, since the quill pen did not maintain its thickness – it was cut and sharpened with a “penknife” all the time. , and the inks did not dry quickly. That is why those scriptures did not exist before that invention in the mid-19th century.

Sarmiento, a great modernizer, insisted that to build a Nation it was necessary to have an efficient and cheap mail and telegraph: the key was to be able to communicate. Not coincidentally, the first section of what is now the Casa Rosada was the post office building, on the corner of Balcarce and Hipólito Yrigoyen, built between 1873 and 1879 by the architect Enrique Kihlberg. The Palace of the Governors still stood next to it, but no one thought of using it for the State - it was in ruins - and for the president there was the Ezcurra residence on Moreno Street or even their private homes. . Using this space of enormous urban significance for a post office palace was the true symbol of the new era. The project for a new building for the executive branch was by then a fantasy that no one had had. During his administration, almost five thousand kilometers of telegraphs were built, a transoceanic cable was inaugurated in 1874, the railroad continued to be extended, and bridges were made of masonry and iron instead of wood to improve roads.

Letter to Commander Antonio Descalzi written in 1873 [It is preserved in the General Archive of the Nation]

Rapid communications moved commerce and culture (what was called “civilization”), generated a better quality of life in many ways and helped imagine a new country, far removed from the economic-social model of the previous era. A rapidly communicated universe was developing. It was undoubtedly the construction of the new industrial capitalism and communications were one of its driving forces.

Cheap and simple mail, with envelopes of standardized dimensions, managed by the state and with official printed stamps, had begun in the United Kingdom in 1840 at the impulse of Rowland Hill, who knew how to devise the Penny Post, that is, the stamp cost one penny. . The problem in our country was that this modality could only be achieved with an efficient system, far from the carts and post services that still existed. However, the change was notable and costs began to drop, but the distances were enormous, the roads were bad, and the infrastructure took time to be improved. The arrival of the mail to the towns was one of the symbols of so-called progress until not so long ago. And let us remember that until that time letters were a written sheet of paper that was folded and then sealed because the idea of the envelope, our simple and usual envelope, did not exist: paper was still a luxury. And the word used for that wrapper invented at that time was not exactly the right one: it was not to put anything underneath [Latin, “super”] but inside, but that's the language and the uses of inexplicable words.

Sending letters was expensive since payment was made according to weight, and even if very thin and light letter paper was used, each gram had to be paid for. This led to the invention of writing systems that seem impossible to us today, such as crossed lines.

* Special for Hilario. Arts Letters Trades