«The fact of getting the signatures of people that one admires, be it because they excel in intellectual, scientific, artistic or sporting fields that one goes through as an amateur, or simply because they have skills that one does not have, implies something like achieving for oneself an unrepeatable trace, a piece of that person also unrepeatable, a minimal relic that keeps her firm in our memory and links us forever with her. This is how I wrote, regarding the collection of musical autographs – of 'classical' music, I clarify so as not to raise false expectations - that I was putting together since my youth and that continued to grow and diversify until today, and that I now present, especially revisited , for Hilario readers.

The concept of “autograph hunter” can be somewhat superficial and volatile, I admit, but I think that in this case the result has grown beyond the personal until it has become a documentary record of the intense activity displayed by the musical protagonists – composers, conductors, instrumentalists, singers, even various orchestras and ensembles – in our country and in the world [1]. Because the catalog is not limited to the musicians who visited us but includes many others, top-level, who did not [2]. With the addition that a good part of the collection consists of drawings and watercolors made expressly by the subscriber to support the respective autograph, and many of them made as a justifiable excuse to personally approach the artist, prolong an interview, extend a dedication or simply record the trace of a specific concert or opera.

Some significant examples of this happened with the prestigious composers who, starting in 1964, gave seminars and courses in the heroic years of the remembered Di Tella Institute where, columned next to vertical strips that I made with more or less abstract musical graphics, I was able to gather the signatures and some bars by Malipiero, Olivier Messiaen, Aaron Copland, Penderecki, Maderna, Luigi Nono, Pierre Boulez and Philip Glass, among others. Also during those years (basically from 1958 to 1975), and over many intervals in the Monday concerts at the Teatro Colón, I managed to gather together in a single parchment – actually a simple sheet of paper, successively rolled and unrolled – the signatures of 44 notable Argentine composers, from Josué Wilkes and Pascual de Rogatis to Gandini and Piazzolla, passing through Caamaño, Gianneo, Ginastera, Hilda Dianda, the Castro brothers and several others. Documents that preserve the imprint of the famous protagonists of that time and the memory they have left us of those opportune times for Argentine musical creation.

But let's go back to the beginning of my daring collecting, started several years before these already conscious youthful incursions. In reality, it all began in 1951, when he was barely eleven years old; Encouraged by the contacts of my piano teacher and with the unexpected complicity of a concierge at the Plaza Hotel, in the same morning I obtained the autographs of Beniamino Gigli, Wilhelm Backhaus and Arturo Rubinstein. I didn't know anything other than their names, but going every Monday with my father to the Wagnerian concerts and on Wednesdays (evenings!) with my mother to the Colón operas - plus what the pasta records and my music provided musically at home. piano lessons – was decisive in opening my ears to music, meeting its performers and beginning to fill out a brand new rubber notebook with their weekly signatures.

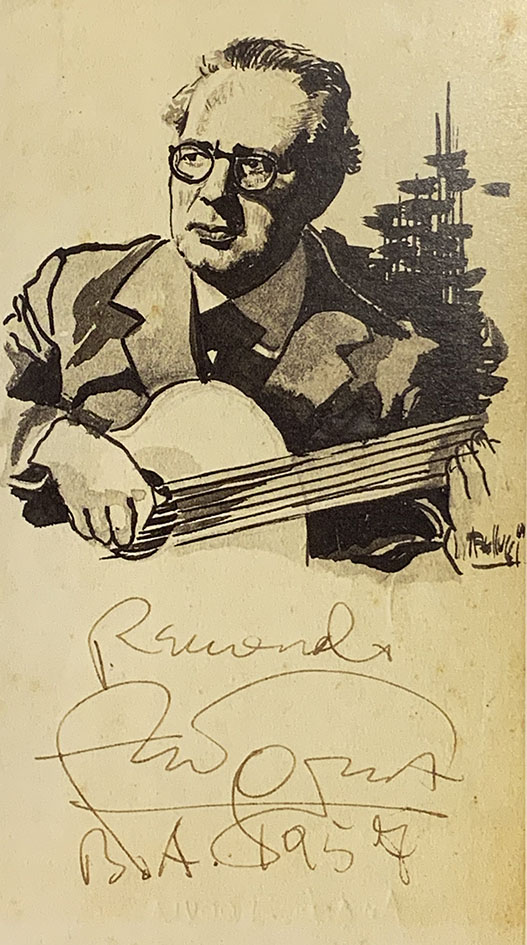

Then, in the early sixties, I made an effort to mail portraits in Indian ink and wash to celebrated artists who never came or had not visited us for a long time, such as Hans Knappertsbuch, von Karajan, Charles Munch, Georg Solti, Sir John Barbirolli , Alfred Cortot, Gyorgy Cziffra, Lotte Lehmann, Peter Pears, Schwarzkopf, Antonio Janigro, Andrés Segovia, etc. (I always try to forget those who never answered me...) A special case happened with Glenn Gould, the brilliant and eccentric Canadian pianist who sent me his autograph along with a very kind letter, in which he asked me for a copy of the drawing to preserve it for his personal pleasure (a request which I was of course quick to fulfil).

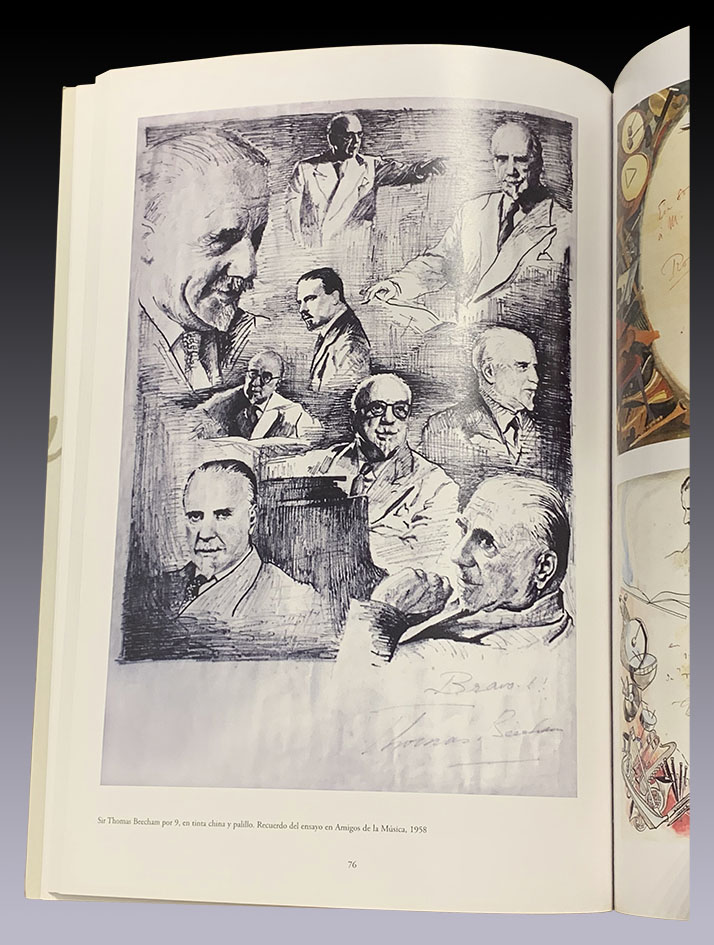

Another special memory I have of Sir Thomas Beecham, on the only visit he made to Buenos Aires, in 1958. Knowing his acid English humor and his aversion to autograph hunters, I prepared a laborious sheet of portraits of him (no less than nine faces !) drawn with Indian ink and toothpicks. At the end of his rehearsal for his only Mozart concert in the Colosseum, I advanced, gritting my teeth and without hesitation, to the podium and faced him head on, with the sheet unfolded. He blinked, was amazed and asked me what technique I had drawn it with: I managed to answer "with black ink" but I missed the translation of 'toothpick' and I only managed to imitate the peeling action. He laughed, and added “bravo!” to his signature.

My catalog also includes the complete roster of two symphony orchestras – the Manchester Hallé, which came here under the baton of Stanislaw Skrowaczewski in 1992 – and, thirty years earlier, a cardboard with the signature of the members of the remembered (and unfortunately disappeared) ) OSLRA, which was based at the Faculty of Law, sets up a chapter of the collection that is nourished by two or three dozen of the most famous trios, quartets, quintets, choirs and cameratas that passed through our country.

Frequent attendance at musical shows (after studies, courses and activity as a choreographer, since the early seventies I had debuted as a music critic), attention to my primary activity as an architect and university teacher and the growth of my family responsibilities – we already had four children to take care of – led me to simplify my autograph productions and make them more standardized. This is how I introduced the watercolor model of hand and baton for conductors (at first there were two hands, inaugurated by the black conductor Dean Dixon, but then I suppressed the left one for the more than thirty that followed), the 'stains' of sheet music about staves or various syntheses for composers, silhouettes of an open piano for pianists and different schemes designed for other instrumentalists. One or another of these items includes the composers Paul Hindemith, Darius Milhaud, Werner Henze, Witold Lutoslawski, William Walton and Luciano Berio, the conductors Daniel Barenboim, Zubin Mehta, Previtali, Baudo, Leitner, Karl Richter, Kurt Masur and Riccardo Muti , pianists such as Bruno Gelber and Horacio Lavandera, Geza Anda and Magaloff, Ingrid Haebler and Rosalyn Tureck, violinists David Oistraj, Pinchas Zukerman, Shlomo Mintz and Gidon Kremer, cellists such as Pablo Casals and Janos Starker, lutenists and guitarists such as Narciso Yepes, Andrés Segovia or Giuseppe Anedda, etc.

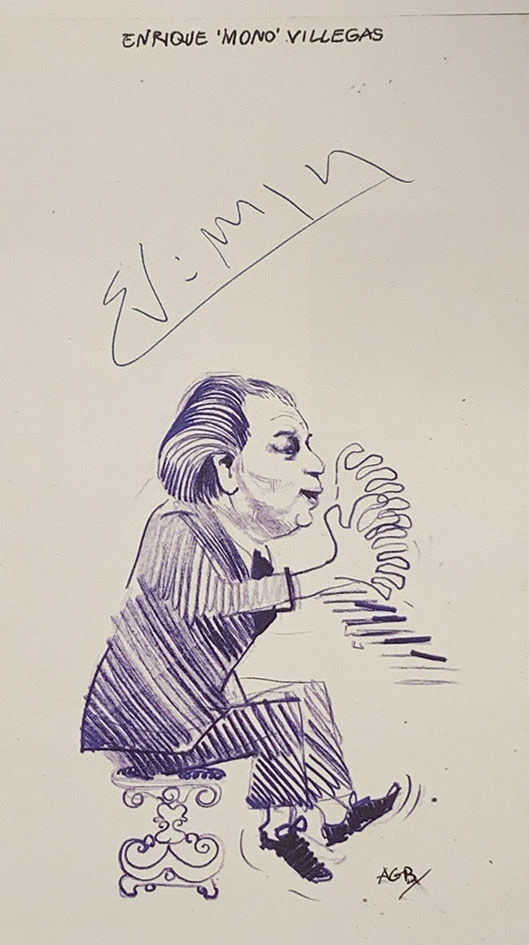

A few caricatures also reflect certain specific opportunities in which I was able to contact and meet artists, either through my temporary activities as an interviewer on television (1979/82), or some performance as a choreographer in symphonic-choral works - Liszt's “Faust” Symphony, with Alexander Szenkar, Requiem, by Mozart, with Rodríguez Fauré – or attending recitals and occasional social gatherings. Among others, I remember Enrique Mono Villegas, who I caricatured during one of his expansive recitals, Lorin Maazel, surprised in the middle of a press conference, Menhajem Pressler and John Ogdon drawn during a rehearsal and Trevor Pinnock in a street meeting.

But due to my increasingly intense closeness to opera, including my interest in its literary, theatrical and scenic aspects surrounding music, I continued inventing individual drawings for the different productions, with the intention of dedicating them to the cast's signatures. responsible for each one. This is how the great Mozartian and Italian titles followed one another, the Wagnerian seguidilla of the 70s/80s, the Straussian creations that used to accompany each season, the local premieres of “Benvenuto Cellini”, “King Roger”, “Katia Kabanova” and “Le grand Macabre” and also – why not – several portraits and individual borders for the most outstanding singers who visited us in the unforgettable lyrical seasons that occurred between the 60's and the 90's.

Among the most interesting items are two signed pages that can be considered historical: Beethoven's 9th Symphony, which Juan José Castro conducted, recently returned from his Australian exile, to open the 1958 Colón season, and Puccini's “Tosca,” which Plácido Domingo and Eva Marton decided to perform here in May 1982, in the middle of the Malvinas war. Two documents that I see as knots that tie the memory of paths veiled with the echoes of history.

I could continue mentioning names, signatures and anecdotes of so many memories, currently totaling well over a thousand objects that remain framed or pressed on top of each other, like the multiple layers of an onion. What was born and grew with the passion of a personal impulse whose experience, I recognize, cannot be transferred, nevertheless today acquires the value of a testimonial ensemble of a time of very intense musical development in our country and preserves the written imprint of national figures and internationals who were its most relevant protagonists.

* Special for Hilario. Arts Letters Trades

Notes:

1. I include later donations – several family ones, since my paternal great-grandfather, Guglielmo Bellucci, was an active musician and orchestral director in Buenos Aires between the centuries – that extended the chronological limits of the collection towards the final decades of the 19th century, with cards, photos and signatures of Puccini, Cilea, Panizza, Charpentier, Franz Lehar, Ignaz Friedman, Rosa Ponselle, Regina Pacini and even the Buenos Aires archbishop, Monsignor Antonio Espinosa, censoring Vagner's “Parsifal” (sic).

2. This speaks of the importance that the mail had until the end of the 20th century to guarantee the sending of written traces (not digitized), something that current communication technologies have made fall into disuse.