The work, one of the most cited paintings of the federal period in the history of Argentine art, came to light in the 40th Online Auction of our house and stirred the waters this summer. Its last public appearance had gone almost unnoticed by scholars: it was in the exhibition Iconography of the Río de la Plata, in October 1989, held by the L´Amateur Gallery of Buenos Aires. Among researchers, the obligatory reference was its reproduction in Monumenta Iconographica [Buenos Aires, Emecé, 1964], the great essay by Bonifacio del Carril and Aníbal Aguirre Saravia, where it is also discussed in two sections and with the incongruity of mentioning it as a watercolor and then as an oil painting. [1] And then, ostracism...

However, the artistic quality of the painting and the enigmas triggered by the intimate scene of a young lady from Buenos Aires getting ready in front of the mirror, aroused the interest of specialists and the general public. For more than half a century it was approached from different angles of interpretation and even starred on the cover of some literature books.

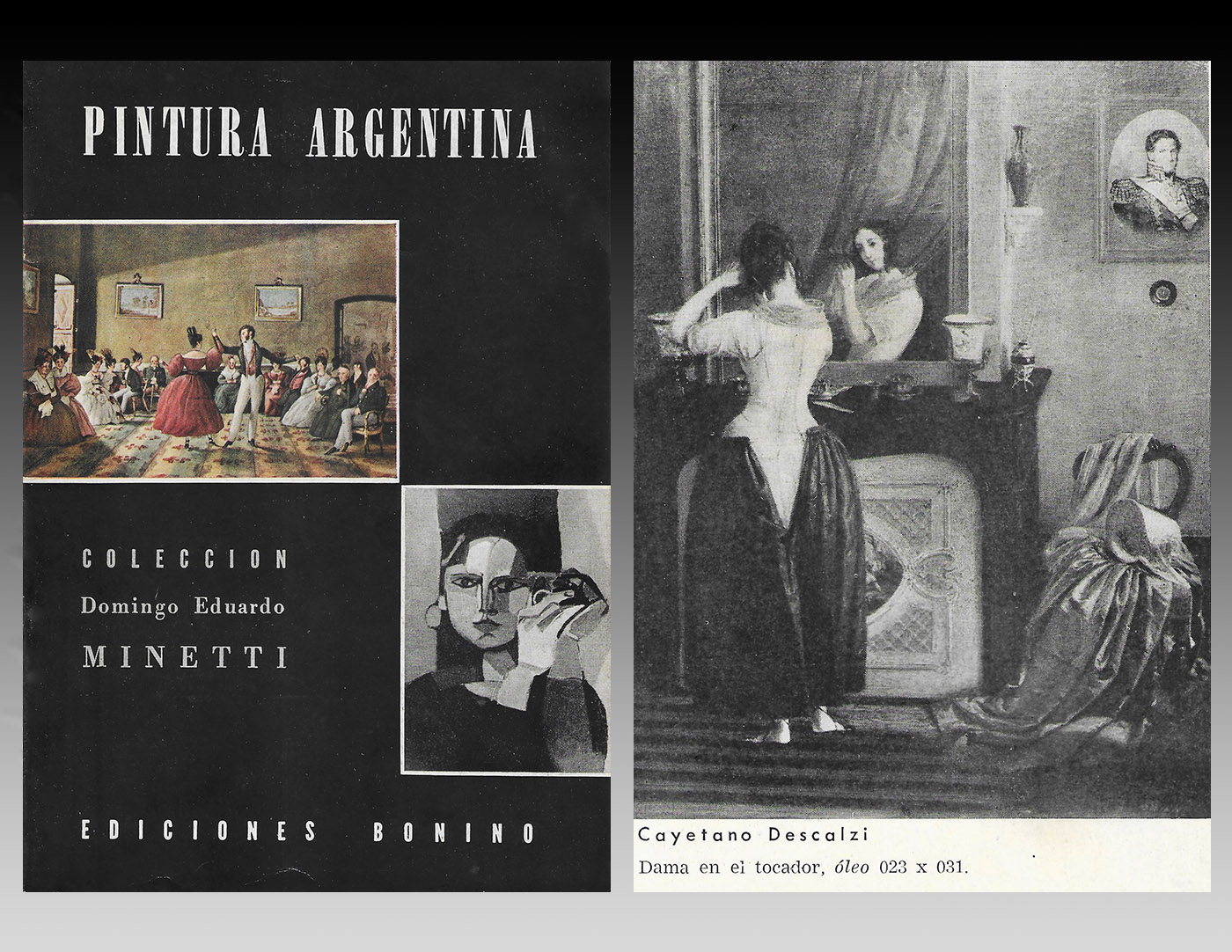

When the work arrived at our space, we began to study it and found various signs that confirmed that we were looking at the copy reproduced in the Monumenta Iconographica, such as small marginal missing parts covered by the frame, which appeared on the plate printed in 1964. In addition, it arrived with the documentation that traced its journey from two years before the publication of the book by del Carril and Aguirre Saravia, indicating that it would be included there, and that it had been part of the collection of Bonifacio del Carril himself. This is indicated by the sales receipt issued by the L´Amateur Gallery, whose directors cultivated a friendship with that collector, bibliophile and editor. Since 1990, the Boudoir Federal remained in the home of another prominent collector, who devoted himself to its study and managed to gather complementary information, such as the catalogue of Ediciones Bonino entitled «Argentine Painting. Domingo Eduardo Minetti Collection, 1956. Among the works exhibited, the first – reproduced on a full page in black and white – by Cayetano Descalzi, “Lady at the boudoir”, an oil painting of 023 x 031, is the second version known and mentioned in the Monumenta Iconographica. Both versions have enormous similarities, although also a few differences [2], highlighting among them the absence of the guitar, and for Bonino it was the work of a single artist, Descalzi.

However, the subject of authorship had also been a topic of conversation, and we found a new piece of information. In the Monumenta... and from then on, in all the citations, Gaetano Descalzi and an unidentified artist were indicated as authors; both signed the painting at the bottom and to the right with their initials: G.D. and C.B. But the truth is that, when we were able to study it in detail, we noticed that the companion of the Italian master Descalzi had signed it with the letters “G.B”, without a doubt.

The researcher Roberto Amigo attempted an answer to this enigma by warning that, given the way in which both authors are represented, «with the second initial in italics and different calligraphy, assuming that both were from the same hand leads to an erroneous reading». And when looking for the second artist, holder of the initials G.B., one could think – according to Amigo – of the «Italian Gerónimo Bastini, hydraulic engineer and portrait painter who published advertisements in 1837 in the Diario de la Tarde, and is last recorded in January 1838, [although, he points out, we are faced with the] only data of his activity reiterated in the bibliography since the 1940s.» [3] Given the frequent austerity of the information available, for Amigo it is an option to study despite the fact that there are no known records of his presence in Buenos Aires in the years of probable dating of the work, after 1842. This researcher in his searches for foreign artists in the region located the record of a Jerónimo Bastiani active as a military engineer in Rio Grande do Sul in December 1838, perhaps the same Italian engineer incorporated into the republican forces.

The practice of work between two authors was recurrent in the academies, and even in the workshops where together with the teacher there were various assistants... And even more, it happened between authors of high public recognition, as did García del Molino and Carlos Morel, his friend and fellow student. Two miniatures with portraits of Juan Manuel de Rosas and Encarnación Ezcurra, his wife, attest to this, initialed by both and dated 1836. Notable examples in 19th century art are also the works by Pallière-Sheridan and Blanes-de Martino.

For Roberto Amigo, "it is probable that the work was designed in Paris during Descalzi's trip, given the subject matter and representation of a bourgeois female interior, so it can be dated to around 1842."

And now, dealing with its technique and without a study of the pigments and substrates [which would be ideal for a precise certification of its materiality], we understand that the work was made by combining various techniques, such as watercolor and gouache - both water-based paints - together with fats such as oil and pastels, accompanied by graphite, on paper, mounted on cardboard. These practices were chosen by the artists to generate soft colors and surfaces coexisting with other intense ones, while giving it a high degree of definition in the details. Such a combination could have led del Carril and Aguirre Saravia to catalog the painting in separate entries as watercolor, and later, oil. [4]

Rosas the Great in the private space

The Federal Boudoir shows us the young woman half-dressed – or undressed – in front of the mirror, placed over a large fireplace used as a dressing table. Boudoir designates the room, next to the female bedroom, used as a space for intimacy and feminine grooming. The decorations and furniture indicate European tastes and fashion, but here other elements mark it as a Rioplatense and Federal space: a guitar hangs next to the mirror and on the mantelpiece, a gourd and silver mate, in addition to the ornamentation of porcelain glasses mounted in bronze and other objects of use, such as the cup and the comb. To the right, on the wall, the lithograph Rosas the Great, a French print of the portrait of the governor of Buenos Aires made by Descalzi himself in 1841. If we return to the lady, we observe that her dress, hat and blanket have already been removed, placed on a chair. She still has the shirt, the petticoat, the corset, and most importantly, the bright red scarf around her neck.

«The annulment of the boundaries between private and public space – explains Roberto Amigo in a text from 1999 – has illustrative examples in the plastic arts of the period. In Boudoir federal [c. 1845] by Cayetano Descalzi and a collaborator. A woman with her back turned is grooming her hair in front of the mirror that offers the viewer the reflection of her youthful face. The iconographic theme of the woman at the boudoir had its heyday as gallant painting in France and throughout the 19th century it was defined as a representation of the prostitute, already removed from the allegorical meanings of its origin. Descalzi did not omit the erotic elements of the subject: the mirror and the comb – symbols of vanity and lust –, the chair occupied by the clothes and the corseted body of the woman offered to the viewer's gaze. Furthermore, as in a mirror game, a decoration of gallant subject is almost hidden by the female body. However, the shift towards the local descriptive is very strong: the red handkerchief, a mate and the detail that captures the attention: a large print with the military effigy of Juan Manuel de Rosas. It is the lithograph put up for sale in Buenos Aires in 1842, known as Rosas el Grande, executed with a drawing by Julien, based on a model by Descalzi who travelled to Paris to check the printing of Lemercier. This lithograph replaced the previous portraits "that did not seem appropriate to occupy the first place in the salons of this city and in the public establishments where federal patriotism and the gratitude of the employees have spontaneously wanted to place them." [Gaceta Mercantil, 18.04.1842]. Descalzi prevented the printed gaze of the Restorer from being directed towards the woman, occupying the absent place of the lover; in addition; a miniature of a family portrait cancels the proximity between the image of Rosas and the clothes thrown on the chair. To give greater ambiguity, a guitar, an instrument of love conquest in the Río de la Plata, compositionally compensates for the lithograph. In this way, the image of Rosas, guarantor of Christian morality, is present even in the intimacy of the porteño woman, whose red scarf, tied around her neck, indicates the impossibility of the relationship between subjects outside of belonging to a common political identity. In contrast to the rich ambiguity of this work, another female representation is the condensation of the long development of visual propaganda of Rosismo in all its aspects: the portrait of Manuelita Rosas painted by Prilidiano Pueyrredón.» [5]

The presence of the portrait of Rosas in the intimacy of that room was also the subject of analysis in the text by Marcelo Marino cited [see note 2], who maintains: «And if the nude is a form of visual rhetoric that includes the half-dressed body, it could be said that this image transits through this category or through an intermediate stage.» Marino notes that the young woman displays her underwear, which is placed under the dress, describing that “textile still life”, as he defines the parts of the dress placed on the chair, and immediately alludes to the portrait of Rosas on the wall, that male presence that defines a reading of the image in an erotic key. “The extra ingredient in the Federal Boudoir is that Rosas not only attends the scene as a voyeur of a private act, but is also witnessing and supervising the construction of the federal body. The image that represents him on the wall is the one designated as the most important among all the iconography of the Restorer.”

For the doctor of letters Alejandra Laera, specialized in Argentine literature [6], who dealt with the subject in an article published in the newspaper Clarín, the scene raises questions and more questions: "Has she just taken off her skirt and headdress? Is she putting barrettes in her hair or freeing it from them? And that hint of a smile that we see reflected, does it announce the evening that is coming or, rather, does it allude to the one that has passed? The scene is of the purest intimacy if it were not for the fact that from the back wall everything is observed, unscathed in his portrait, by the governor of Buenos Aires Juan Manuel de Rosas. The play of glances traces lines of force between the private space and the public space that are as subtle as they are firm: the young woman observes herself and through the mirror also the artist and those of us who see his image; Rosas observes the entire scene, almost watching that artist and even the spectators; The artist, for his part, observes the young woman posing for him half-dressed, and we witness a scene of domestic intimacy in which we immediately recognize, at the same time, a portrait of the exercise of power.» [See]

Among the elements represented, the guitar also inspires other questions: a symbol of gaucho culture? Or perhaps, as Laera maintains, «does the guitar not indicate that this French interior, instead of belonging to a lady from Buenos Aires, as it was generally understood, has been adapted for a young woman by her lover, surely, he, yes, a son of the elite?» For Melanie Plesch - an Argentine musicologist living in Australia, where she teaches at the University of Melbourne - «the guitar is not included as a popular symbol but, on the contrary. This is not the instrument of the gaucho but of the well-to-do classes. It is the so-called “French” guitar, which is distinguished by single strings [instead of double] and the decorated bridge [“with a “mustache”].” [7]

The auction

The discovery of the work awakened the atmosphere from its summer siesta, and we include in this reaction art scholars [8], museum officials and directors, journalists and of course, collectors. The Boudoir Federal was thus once again the protagonist of the most diverse conversations. The news appeared in separate newspaper articles signed by Alejandra Laera [Clarín digital] and Daniel Gigena [La Nación digital: See and the exchange of queries was very intense on the days of the exhibition.

From the Fernández Blanco Museum in the city of Buenos Aires we were informed that the work – in a previous choice – was a leading part of the Federal Room intended for one of its headquarters, and from other museum institutions we received the desire to acquire it for their heritage. But the official coffers... what more can we say about that!

The truth is that, at the close of the online auction, there were six interested parties bidding for the work, all private individuals and committed to providing it – if they were the lucky purchaser, we had arranged it with each of them – for public exhibition. As happens when a treasure comes to light in this way, the final minutes were dizzying and the "electronic hammer" closed at the sum of 59,000 dollars plus commission and purchase tax. Hours later we learned that a banking institution had remained expectant in the bidding until its budget was exceeded by the flow of offers. They were willing to acquire it and donate it to a national museum.

The following day, the newspaper «La Nación» published a full-page article on this news, with a majestic reproduction of the painting. An eighty-year-old client, a faithful reader of this newspaper since his childhood, told us: «I don't remember a one-page article referring to the sale of a 19th-century Argentine painting. I congratulate you.»

Notes:

1. In the two-volume edition, in volume I: Commentary and description of the plates, pp. 66 and 112. And in volume II, Plates, plate CXLII. It is striking that in the paragraph commenting on the work, it indicates that it is a watercolour [p. 66] and in the “Descriptive catalogue of the reproduced pieces” it is mentioned as an oil painting [p. 112, as in the reproduction of the work, Plate CXLII]. Probably, only Susana Fabrici - now deceased - and Roberto Amigo had observed this work in person before its current exhibition.

2. In reference to the version of this story, the one that formed part of the Minetti Collection "differs in the turn of the head of the woman reflected, who instead of looking at the spectator like the one that appears in the Monumenta Iconographica, has a more logical position in relation to her location in front of the mirror. The arrangement and the number of elements on the dressing table also differ. The guitar on the wall does not appear in this case [...]». In Marcelo Marino, Fashion, body and politics in visual culture during the Rosas era, note 19. Text published in Baldaserre – Dolinko [editors], Travesías de la imagen. Historias de las artes visuales en la Argentina. Vol. I. CAIA/UNTREF. 2011.

3. Personal communication from Roberto Amigo prior to the auction, included in the auction catalogue.

4. We are grateful for the information provided by museologist Bibiana Osvaldo.

5. Roberto Amigo, “Prilidiano Pueyrredón and the formation of a visual culture in Buenos Aires”, in Prilidiano Pueyrredón, Buenos Aires, Banco Velox, 1999, p. 34-36.

6. Alejandra Laera, professor at the University of Buenos Aires, director of the Instituto de Literatura Argentina “Ricardo Rojas”, principal investigator at CONICET, is the author of numerous books, including anthologies, among them Una historia de la imaginacion en la Argentina [2019].

7. Melanie Plesch, in personal communication. Dr. Plesch has specialized in the intersections between music and politics, especially the relationship between academic music and the construction of national identities, highlighting her pioneering application of topical theory to the study of Argentine musical nationalism.

8. We were also visited by Carlos Masotta, anthropologist, professor at the University of Buenos Aires, member of CONICET, specialized in the analysis of the image and the political problems of social representation of collective memory and ethnicity. Another researcher who had addressed the Federal Boudoir in his texts.