“poetry with colors, and […painting] based on words.” [1]

Aurora Reyes (1908-1985), known mainly as the first Mexican muralist, was an outstanding and multifaceted artist who, through her creative production, both plastic and literary, documented and interpreted the history and feelings of the people of Mexico. modern.

Identified with the so-called Mexican School, both for her social commitment, her realistic style, and her interest in indigenous culture, Aurora was a true “tlacuila” [2] of the 20th century because throughout her life she He dedicated himself to writing by painting and painting by writing. In fact, most of her poems and murals not only narrate the main popular struggles of post-revolutionary Mexico, and especially those waged in defense of women's rights, but also manifest a great lyrical sensitivity.

Although Aurora was a leading figure in the fascinating artistic and political environment of her time, over the years her work, like that of many of her female artist colleagues, began to be made invisible and forgotten. With this text I propose, then, to review some important aspects of his life and work, not only to begin to settle an important historiographic debt, but mainly, so that we can continue enjoying the historical, political and aesthetic richness of his outstanding production. artistic.

The life of the artist

Aurora Reyes was born in Hidalgo del Parral, Chihuahua, Mexico, on September 9, 1908, just two years before the outbreak of the Mexican Revolution. [3] In 1913, Aurora's father, Captain Léon Reyes, due to the participation of his father, General Bernardo Reyes in the tragic decade, and his political convictions, had to flee his city and remained hidden for around one year, while the rest of his family, also clandestinely moved to the capital, since the threat of punishment fell on all its members. To survive, Aurora's mother, Luisa Flores, baked bread, which the little girl sold at the Lagunilla market. Suddenly torn from her comfortable life in Chihuahua, Aurora witnessed and suffered firsthand the harshness of life for the country's most marginalized classes.

Aurora's experiences in the poorest neighborhoods of the city formed her strong and passionate character, and had a decisive influence on the political convictions that encouraged her to fight, throughout her life, on behalf of the poor, with a commitment and unmatched social awareness. The artist herself was aware of the intimate relationship between her personal life and her political convictions, and assuming the power of her situated knowledge, she once stated: "I am interested in these social issues because I have been hungry, I have suffered misery firsthand and because I am people of the town. I am interested in him because I belong to him. And I consider that art is the medium that penetrates the emotion of beings and that is why it constitutes a powerful weapon to fight for the people.» [4]

When Aurora grew up, and the political persecution against her family finally stopped, she began studying at the National Preparatory School and when she turned 13, she joined the National School of Fine Arts, taking painting classes at the night time. Despite all the material hardships she suffered, Aurora graduated in 1924.

Just a year later, in 1925, she achieved the first solo exhibition of her drawings. The same year, when the young artist was only eighteen years old, she married the journalist and writer Jorge Godoy. [5] During the short time in which the couple remained married, Aurora gave birth to two sons, Héctor born in 1926, and Jorge in 1931, almost simultaneously with her divorce, an unusual and very difficult circumstance for a young woman. in Mexico in the 1930s. After the divorce, Jorge and Aurora did not see each other again and the responsibility of raising the children fell exclusively on her.

From 1927 onwards she had begun to earn a living as an art teacher in public schools in the capital. In 1930 she exhibited her work with other fellow teachers at the first collective exhibition of posters and photomontages organized in Mexico City. And in 1936 she was a founding member of the very active group of artists known as the League of Revolutionary Writers and Artists (LEAR), which would soon become one of the most creative artistic centers of the decade. Many of the league's members were also dedicated left-wing political activists, mainly from the Mexican Communist Party. They considered themselves academic workers and assumed a very important social responsibility that transcended the field of artistic creativity. The stimulating discussions, lectures and other activities organized by LEAR members left a great influence on Aurora's artistic and political career.

During the 1930s, a period of history that was very active in art and politics, Aurora formed deep friendships that would last a lifetime with prominent artists and thinkers of the Mexican intellectual milieu, such as the painters Diego Rivera (1886-1957). ), María Izquierdo (1902-1955), José Clemente Orozco (1883-1949) and Raúl Anguiano (1915-2006); the composer Silvestre Revueltas (1899-1940); the writer Renato Leduc (1898-1986); and the Cuban poets Juan Marinello (1898-1977) and Nicolás Guillén (1902-1989). Her friendship with the visual artist Frida Kahlo (1907-1954), and with the folklorist and activist Concha Michel (1899-1990), represented by Aurora in her work Concha, Aurora and Frida (1949), was particularly close and of great impact. in artistic production and in the fight for women's rights of all three. [6] Aurora was also very close to the anthropologist Eulalia Guzmán (portrayed by the artist in her mural in the Auditorio 15 de Mayo), whose knowledge of pre-Hispanic Mexico she frequently drew on for her artistic production.

Aurora Reyes, Concha, Frida and Aurora, 1949, oil on canvas. Héctor Godoy Lagunes Collection. Reproduction permission: Héctor Godoy Lagunes. Photograph of the author.

In 1936, Aurora painted her first public work, thus beginning a promising career in the field of mural painting. During the 1940s, Aurora began to write and publish poems, and when she found the time and energy necessary, she continued painting and participating in individual and group exhibitions both in the country and abroad, developing a significant body of work characterized by a great expressive force and a notable social commitment.

Her fight for women's rights

Aurora's intense activity as a trade unionist is a significant testimony to the beginnings of the movement for women's rights in Mexico. From an early age, the artist was a member of the Mexican Communist Party, which she however renounced due to the sexist abuse of her colleagues.

In 1936 she entered the Center for Women's Social Studies of Mexico where she was chosen to serve as Press Secretary. In 1937 she was a representative of the Union of Technical Schools in the National Congress for Popular Education in Mexico, she was Secretary of Labor and Conflicts in the Executive Committee of the Union of Art Teachers and also participated in the Single Union of Private School Workers. Let us also remember that in 1937, she, together with Michel, founded the Women's Revolutionary Institute. Starting in 1938 she held important positions in the Union of Teaching Workers of the Mexican Republic (STERM) and in the National Peasant Confederation (CNC).

Through her participation in the teachers union, Aurora defended the rights and participation of women, not only within the different teaching organizations of the time, but also in government positions. Among other important aspects, Aurora promoted the right of women to vote and be voted, the extension of maternity time for women, the recognition of the time necessary to breastfeed the babies of working mothers, and the creation of daycare centers in schools for teachers' children.

Through her participation in the teachers union, Aurora defended the rights and participation of women, not only within the different teaching organizations of the time, but also in government positions. Among other important aspects, Aurora promoted the right of women to vote and be voted, the extension of maternity time for women, the recognition of the time necessary to breastfeed the babies of working mothers, and the creation of daycare centers in schools for teachers' children.

In many of her lectures and writings, she highlighted the need for direct female intervention in the creation of a comprehensive cultural project for the nation. Remembering those years, Aurora once said that “[…] doing an analysis of the process of Culture throughout the History of Humanity, we find that in the culture of this time the set of values that form it are, despite its importance, insufficient to meet the needs of a humanity composed of women and men, since until today, Culture in general, has exclusively masculine characters since it has been developed by them and for them, leaving women to a greater or lesser degree, and in all her activities as a tutor, she is a slave and exploited of the exploiting man or slave […]». [7]

Aurora's clear and advanced gender awareness, even when it created certain conflicts with other activists with whom she shared her political convictions, consistently guided her personal life, her academic discourse, her public actions, and her artistic career. Aurora, and other distinguished women of the time, such as her friend Concha Michel, knew that socialist ideals were not enough in themselves to solve women's problems. In the same way that Aurora's male colleagues denounced the unjust relations between different social classes, the female artist and activist denounced the unequal relations between men and women, an integral part of the capitalist system, usually ignored by political parties and the artistic organizations of the time.

His literary production

Although Aurora was primarily a professional painter, in art circles she is generally more recognized as a writer. She began this march with Hombre de México in 1947, it was her first poem published in mural sheets published by the Autonomous University of Mexico. Later, in 1950, she wrote Nine Estancias in the Desert and in 1951, Astro en Camino, with which she participated in literary competitions. Her first book, Human Landscapes, was published in 1953. In 1974, Aurora published Words to the Desert, in the book Three Mexican Poets, in collaboration with Roberto López Moreno and Sergio Armando Gómez. In 1981, a compilation of Aurora's works, including a new poem titled Stellar Harvest, was published under the title Spiral in Return.

Aurora's verses are very original in their form and very deep in their meaning. Some, including her first and her favorite, Hombre de México, denote her political ideology, although most are rather intimate and lyrical in tone. Aurora's interest in pre-Hispanic culture inspired her complex worldview and certain vivid and expressive metaphors, used to express the most essential and universal human concerns such as life, death, nature, love, the passage of time, anguish, absence and transcendence.

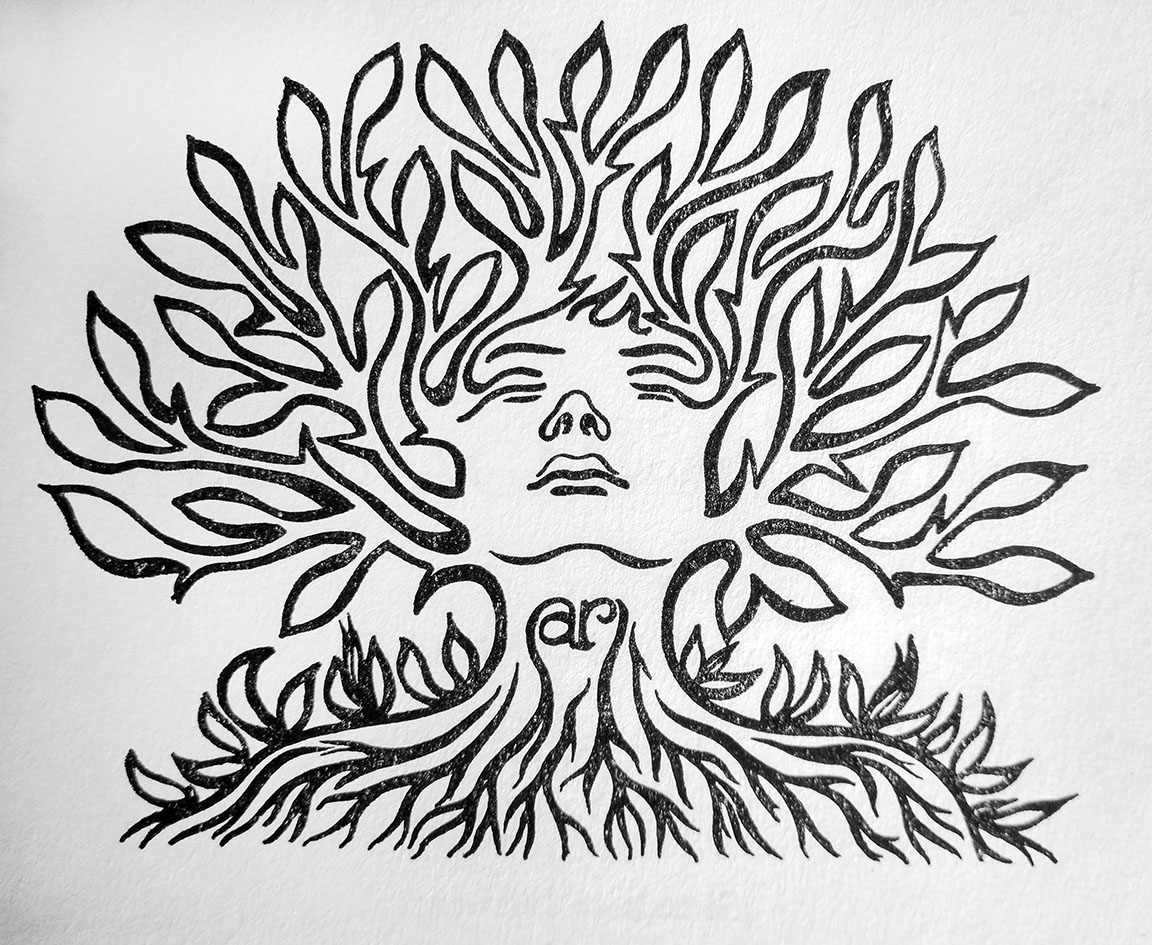

Her books of poems, illustrated by herself, demonstrate that she was able to create expressive intertextual relationships of great interest, especially due to the power of synthesis achieved in her images, which with a few lines summarize and amplify the deep meaning of the poem. sensitive words from her.

His pictorial production

Aurora's paintings are more descriptive and political than her poems, but they also reveal the fine sensitivity, delicacy, and love for life that emerge in her writings. Throughout her life Aurora expressed herself in a wide variety of artistic media and subjects, such as lithographs, for political pamphlets and posters; ink drawings for the illustration of books like those just mentioned; oil paintings on canvas for private commissions such as portraits and genre works; and temperas, frescoes and acrylics for her public commissions.

Aurora’s approach to painting was consistent with the tradition of Mexican art that the artist herself described as “realistic and figurative, and whose content is related to the struggles of the people and the exaltation of their beauty.” [8] Throughout his career, the favorite themes for his posters, easel works and mural paintings relate to his political commitment and his personal interests, such as history, social injustice, women, children and the education.

In tune with most of the artists of the Mexican School, she was concerned with the representation and interpretation of the different stages of national history, and with the celebration of the customs and beliefs of the Mexican people. In her last mural, The First Meeting (1977-1978) in the Delegation of Coyoacán -Mexico City-, she focused on the dramatic impact of the Spanish Conquest on the native population. In some of her easel paintings she emphasized the fight for Independence, and in other works, such as Scenes of the Revolution (1935), she concentrated on one of the most recurrent themes of the Mexican School, the Revolution of 1910.

Aurora Reyes, El Primer Encuentro, 1978. Mural painted in the Political Delegation of Coyoacán, Cabildos Room. © Courtesy Aurora Reyes Estate

On the internet: https://awarewomenartists.com/en/artiste/aurora-reyes-flores/

She also produced some beautiful genre paintings; among them Mercado de Juchitán (1953), and portraits of female figures in regional costumes, such as The Golden Bride (1955), which intersect with her concern for exalting the role of women in Mexican society.

Aurora Reyes, The Mareña Girl, 1953, oil on canvas, Héctor Godoy Lagunes Collection, Permission for reproduction: Héctor Godoy Lagunes. Photograph of the author.

Boy in Front of the Sea (1947), Boys and Star (1948), and La Niña Mareña (1953), are outstanding examples of the tenderness with which Aurora interpreted childhood and the physical and emotional changes typical of the growth process; another of her favorite topics.

Sick Child (1937) summarizes the sensitivity, honesty and passion with which Aurora interpreted childhood. At the same time, the work, with its melancholic tone and the landscape populated by oil towers, denounces the exploitation of the poorest and the cruelty of social inequality that characterized Mexican society during the 1930s. Let us also remember that a year later, in 1938, Aurora would enthusiastically support the oil expropriation of foreign companies ordered by then-president Lázaro Cárdenas (1934-1940).

The analysis of the role of women in the modern world that animated the political activities and the lectures given by Aurora also found their place in her pictorial production. Aurora was a very keen observer, and the models for some of her portraits, such as Portrait of the Kroupskaia (1930), Portrait of Chabela Villaseñor (1938), and Portrait of Frida (1946), combine her interest in the artistic genre with decision to highlight the role of women in education, art and culture. Some of her allegorical portraits of women such as War Woman (1937) are extraordinary, profound and sensitive statements about motherhood, as well as a powerful and persuasive call for peace.

Aurora Reyes, Attack on the rural teacher, 1936, fresco, 30 m2, Centro Escuela Revolución, México, CDMX. Reproduction permission: Héctor Godoy Lagunes. Photograph of the author.

Another of the most recurring issues in her iconography was education, a topic directly related to the artist's own life and the values in which she believed. Indeed, she was convinced about the fundamental role of educators in the construction of a new society and she addressed this theme throughout her life and work, especially in her mural. From her first public work, Attack on the Rural Teacher (1936), Aurora highlighted the important role played by women in education, at the same time she denounced the violence to which teachers were subjected as a result of their social work, and particularly women. [9] Her most complete sequence of ella on the topic of education was her mural cycle entitled Presence of the teacher in the history of Mexico (1959-61), painted by the artist for the National Union of Education Workers (SNTE) . [10]

Aurora Reyes, Dramatic Argument, 1946, oil on canvas, Héctor Godoy Lagunes Collection, Permission for reproduction: Héctor Godoy Lagunes. Photograph of the author.

Conclusions

We can include here, as a final reflection, that the artist Aurora Reyes, despite her extraordinary aesthetic and expressive achievements, and despite the leading role she played in life within the artistic and political movement of the Mexican School, with the exception of a few academic studies and exhibitions, has been unfairly neglected by the historiography of national art.

The writing of this tribute article offers us the extraordinary opportunity to once again appreciate her works, and to reflect on her avant-garde messages regarding the recognition of the role of women in education and art, interpreted from her own voice. the artist, who as a woman and as a precursor of the Mexican national feminist movement, always demonstrated a very deep gender awareness.

Recovering the memory of an artist who, both in her life and in her work, fought for women's rights helps us recover the genealogy of resistance against the many forms of patriarchal oppression, including the invisibilization of discipline of art history. Today it is essential to recover the messages of Aurora Reyes, the modern tlacuila who made "poetry with colors, and [...painted] based on words", in order to continue our own struggle, with her poetic and political impulse.

Notes:

1. Aurora Reyes interviewed by Armando Carlock, El Nacional, June 7, 1971.

2. Tlacuila: voice that derives from Nahuatl. The tlacuilos were indigenous painters-scribes whose origin dates back to pre-Hispanic times.

3. Most of the information about the life of Aurora Reyes was obtained from personal documents and newspaper clippings contained in the Aurora Reyes Author Fund, CENIDIAP/INBAL, Biblioteca de las Artes, CENART.

4. Fragment of an interview with Aurora Reyes, “De Poetesa a Pintora” Excelsior, February 24, 1953.

5. Jorge Godoy wrote The Book of Viceregal Roses. He died in 1949 at the age of 55.

6. For a detailed study of the friendship between the three artists see my article “Frida Kahlo and Aurora Reyes: Painting to the Voice of Michel,” Woman's Art Journal, Vol. 40, no. 2, Fall/Winter 2019, pp. 3-13.

7. See Cardona, Patricia, “Aurora Reyes entered the San Carlos Academy for a beating that she gave to a high school prefect” in Periódico Unomásuno, December 30, 1985, p. 115.

8. Aurora Reyes cited in an article in El Nacional titled “About Mexican painting Aurora Reyes spoke yesterday in Bellas Artes,” March 15, 1958.

9. For a detailed analysis of the work see my article The First Mural Created by a Mexican Female Artist: Aurora Reyes’s The Attack on the Rural Teacher, Woman’s Art Journal, Fall 2005/Winter 2006, vol. 26, no. 2, pp. 19-25.

10. I study this work in my article “Recovering our memory: the women of Aurora Reyes in the mural cycle of the 15 de Mayo Auditorium,” in Emilia Recéndiz Guerrero, Norma Gutiérrez Hernández and Diana Arauz Mercado, coordinators, Presencia y Realidades. Research on Women and Gender Perspectives, Zacatecas, Autonomous University of Zacatecas, 2011, pp. 599-609.

* Special for Hilario. Arts Letters Trades