We know that those images that today constitute our cultural identity were not and are not necessarily our own, in the sense of what is proper, distinctive, typical, corresponding, but that they occupy that place in our imaginary as the result of a long and complex process in which they have become our heritage, that is, they have become appropriate, also in the sense of being adequate, referents, representative. Modern photography in Latin America, and particularly in Argentina, constituted a fundamental moment in this process, given that the contacts, influences, north-south journeys and trans-Atlantic itineraries of migrant photographers, artists and intellectuals in the mid-20th century contributed to to forge the modern and developmentalist Pan-American image – whose trail is still visible in our visual culture – but through foreign eyes. This modern vision that incorporates the traditional to encrypt a vision of the future is in clear contrast to Europe besieged by fascism, Nazism, post-war devastation and decolonization processes.

Since the 1930s, among those fleeing political persecution and anti-Semitism, a surprising number of women photographers arrived in Latin America, dispersing in various countries: Argentina, Mexico, Venezuela, Brazil, Uruguay, Bolivia, Peru. Some already established within the profession and leaving behind their studies, livelihoods and membership groups; others having trained technically and still taking their first steps in independent practice. All of them, facing the trauma of exile, arrival in a land whose language was strange, arrived in cities and cultures experiencing their own process of transformation. Its presence in Latin America – and in some cases its definitive permanence – takes place and intersects with processes of popular mobilization, the years of struggle to achieve the female vote, the emergence of a mass culture that expanded the repertoire of social and professional roles. feminine. The fundamental contribution of this group of female photographers to Latin American visual culture, to the broadening of perspectives and professional practices for women, to the inclusion of pre-Columbian and colonial traditions in the most absolute visual modernity, is still a historiographical project. incomplete, challenged by the disappearance or deletion of its record in the file.

Within the historiography of photography in Latin America, the influence of the avant-garde trends that took place in Weimar Germany and Eastern Europe, in metropolitan cities such as Berlin, Vienna, Prague, Budapest, has been recognized and studied. That fundamental impulse that photographic practice received since the 1920s, extending towards advertising and new forms of consumption; colonizing illustrated periodicals being the ideal record of fashion and its modern tempo; intervening in the political discourse from its daily register of the press, it was also what marked it as the means of visual experimentation par excellence, along with the emergence of mass cinema. The forms of the new vision and the new objectivity — the extreme close-ups, the unconventional framing, the positioning of the camera at dizzying angles, the effects of the copying process with montages, collage, over-prints, over-exposures — contributed to break down and distort perceptual habits, proposing new ways of seeing. Daily life in the first decades of the 20th century in many world capitals was inundated with photography, thanks to advances in rotogravure techniques, the proliferation of lightweight and portable cameras (Leica, Contax), as well as films whose sensitivity allowed negotiate the capture of new spaces. Added to the transmission of images by cable, the illustrated press launched itself to cover events on a global scale and in this way began to lay the foundations of a common visual culture, at the same time that the very notion of photography was diversified in various registers. . As the photographer Lucia Moholy (née Schulz, before her marriage to László Moholy-Nagy) stated in her book One Hundred Years of Photography 1839-1939 originally published in London in the year of the centenary of the invention: “Life without photographs is no longer is imaginable. They pass before our eyes and arouse our interest; They also pass through the atmosphere, unseen and unheard, covering distances of thousands of miles. They are in our lives, just as our lives are in them.” (1)

This is the cultural moment that supports the development of a broad group of women as photographers; born in the first decade of the 20th century, they reach their youth and maturity when the economic and social conditions in Weimar Germany, Austria, Hungary, the Czech Republic became advantageous for them. Those women who had entered the workforce during the first war became firmly established in the public space and remained after it was over. Photography began to offer them a promising professional career. Although not everyone could simply pick up a camera and adopt it as a means of professional or personal expression, the availability of photographic equipment and materials began to expand. Despite the fact that few countries had specialized and well-structured training programs and spaces before 1945, the training method for many applicants was practice in studios, in technical schools where drawing, engraving, graphic design, textile design, coexisted with photography, or simply self-training. As the research of historian Andrea Nelson points out, the emergence of a small but highly specialized and excellent group of programs in Germany and Austria in these decades contributed to an increase in the number of women employed as professional photographers.(2) The Photographishe Lehranstalt des Lette-Vereins in Berlin, part of a vocational institution for women established in 1866, already had a program at the beginning of the 20th century that included the study of graphic printing techniques, later x-rays, and focused on the development of multiple skills practices, instead of teaching an aesthetic program, as will later take place at the Bauhaus. Photographische Lehranstat für Damen des Breslauer Frauenbildungs-Vereins opened in Wroclaw (today Poland) in 1891; as well as other professional schools in Munich, which already admitted women in 1906, where in 1915 the German photographer Germaine Krull was trained. The Bauhaus will open its first program in photography in 1929 and the École technique de photographie et de cinématographie in Paris in 1927. In Austria, the Lehr und Versuchsanstalt für Photographie und Reproduktionsverfahren, opened in 1888 in Vienna, allowing the training of women since its opening. , although not until 1908 the training was imparted in an equitable way, becoming one of the most prestigious graphic arts schools. In the interwar period, two-thirds of all photo studios in Vienna were run by Jewish women.

Part of this training record remains linked to the most outstanding women of this period, whose vital and photographic destinies would continue after exile in Latin America. We know that Grete Stern trained in a similar program with her friend and associate Ellen Auerbach (née Rosenberg) at the Staatliche Akademie of the Bildenden Künste Stuttgart in 1928 before working with Walter Peterhans at the Bauhaus a year later. Annemarie Henrich (SEE) was her uncle's apprentice, but she traveled to Germany in search of further training and was part of several German photographic associations. Gisèle Freund did not receive formal training until her first exile in Paris, where, alongside her academic work on the first social history of photography, she passed briefly through the studio of the photographer Florence Henri and fundamentally acquired her experience as a photojournalist in the offices of VU magazine. Heinrich, Stern and Freund were part of the modern avant-garde in Buenos Aires in the 1940s, sharing intellectual circles of European émigrés, around the magazine Sur, patronage of Victoria Ocampo, and fundamentally turning their production to the illustrated graphic press, in the pages of newspapers, entertainment magazines, even visual guides and photobooks.

Hildegard Rosenthal: Street Scene, São Paulo (Cena de rua, São Paulo). Circa 1940. Moreira Salles Institute.

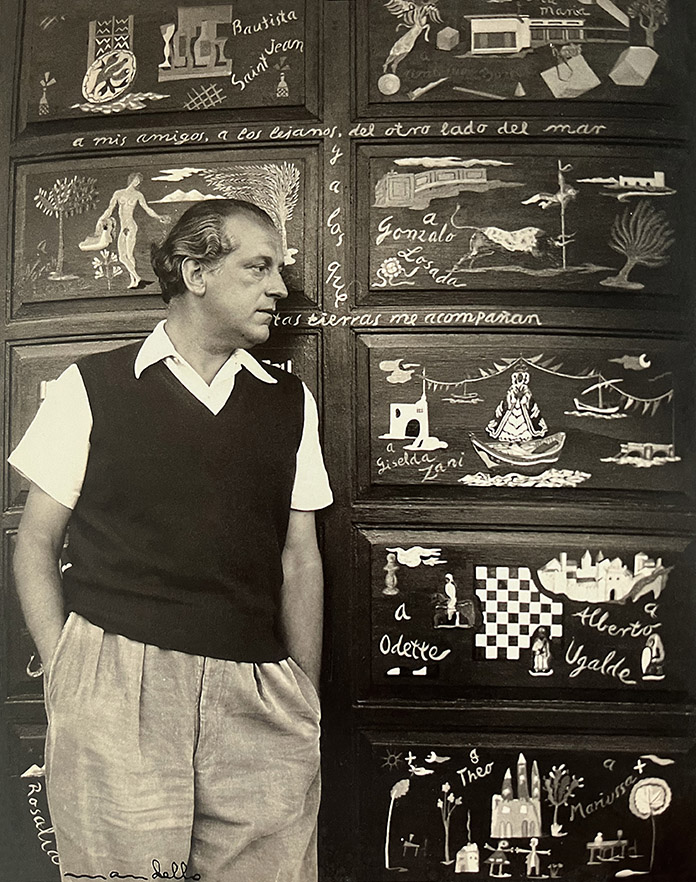

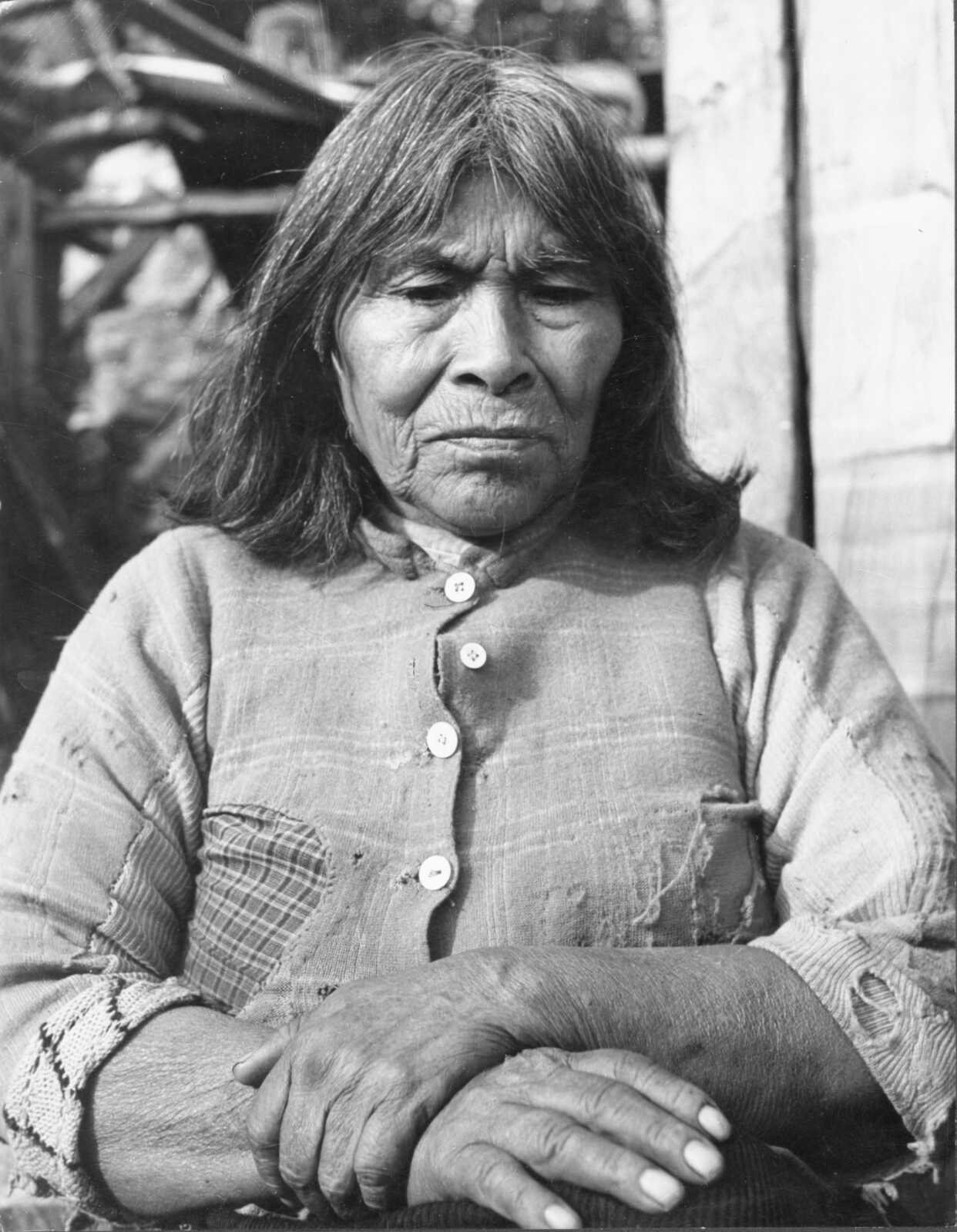

Jeanne Mandello trained at the Lette-Verein in Berlin, then she was apprenticed to Paul Wolf and, together with her friend Nathalie von Reuter, opened her own studio in Frankfurt in 1929. In 1941 she arrived at the port of Montevideo, on the same transatlantic ship that left to Gisèle Freund in Buenos Aires after months in a detention camp in France and having crossed the border into Spain. Mandello, together with her husband, Arno Grünebaum, lived in Uruguay developing her photographic studio until the early 1960s. Also in Wolf's studio and then at the Gaedel Institut, Hildegard Rosenthal (née Baum) acquires an expert use of the Leica and also opens her studio in 1924 in the same city. Rosenthal went into exile in Brazil in 1937 together with her husband Walter Rosenthal, where she developed one of the most brilliant documentary works on the modernization of the city of São Paulo in the following decade. Kati Horna (née Deutsch Blau) trained as an apprentice in József Pécsi's studio, alongside her childhood friend Robert Capa in Budapest; Berenice Kolko was also apprenticed to Rudolf Koppitz in Vienna in the early 1930s. After spending time in Spain doing a photo report during the civil war for the anarchist press, Kati arrives with her husband José Horna in Mexico City, where they settle permanently and where, together with two other European émigrés, Remedios Varo and Leonora Carrington, formed a close community of women artists. Kolko first emigrated to the United States, but following an invitation from Diego Rivera, she arrived in Mexico in the early 1950s — coinciding with Gisèle Freund's stay there — where she began her monumental project “Mujeres de México” and later “ Faces of Mexico.”

These are women photographers whose itineraries, production and contribution to modern visual culture in their adopted countries — from portraiture to reportage, from graphic design to avant-garde experimentation — have so far been documented and studies of their work continue to grow. Despite the fact that it could be suggestive to characterize these artists as a group that shared the same aspirations and went through the same struggles and circumstances, as we delve into each of these exiles, their conditions and their mode of insertion in the countries where they arrived , its ideological and political particularities defy a detailed or homogeneous characterization. What many share is a common starting point: They belonged to middle- and upper-class Jewish families that valued women's education and cultural participation. They have in common the access to education and training in photography, because it offered them a professional career, an independent livelihood and an instrument of expression and self-determination. In her memoir, Gisèle Freund writes, “I had dreamed of making long trips, but I never got to leave Europe. My departure to Argentina was then the beginning of a new experience. Until then I had specialized in portraits, but I knew that now I had a way to get to know the American continent, to be a photojournalist... It was the second time in my life that I had to start a new life, only this time I was armed: I had a profession." (3) In a report made to Kati Horna, she states: “I fled from Hungary, I fled from Berlin, I fled from Paris, I left everything behind in Barcelona… When Barcelona fell, I couldn't go back for my things, I lost almost everything again. I arrived in a fifth country, Mexico, with my Rolleiflex around my neck and nothing else.” (4) Not in a small way, many of these women photographers represent in themselves the figure of the neue Frau, the new woman who in those decades gains visibility and cultural relevance worldwide and photography as a technological means is the instrument that makes it possible to cross the gender, class and educational barriers.

Lola Alvarez Bravo: Frida Kahlo. Mexico. 1943.

But the recovery of this female photographic archive and its enhancement is still a work in progress. Forced exile, the loss of works and archives in journeys that are often arduous and in circumstances of extreme danger have dispersed and gradually erased the traces of these trajectories. Along with these fundamental names, it is necessary to replace that of other women in order to take a true dimension of this contribution to photographic modernity in Latin America. Together with the work of Horna and Kolko, the work in ethnographic photography and the documentation of pre-Columbian crafts and popular culture by Ruth Lechuga (née Deutsch Reiss, who emigrated from Vienna to Mexico with her family in 1939) is preserved today. in the Franz Mayer Museum in Mexico City next to the archive of the poet Wolfgang Päalen, in whose circle other photographers such as Eva Sulzer and Alice Rahon participated, with a similar interest in pre-Columbian culture. Ruth Lechuga's is an archive that not only allows a re-signification of the relationships between avant-garde, surrealism, popular culture and photography, but also her own practice of social anthropology from a gender perspective becomes an object of reflection and revaluation. In another circle of the Mexican capital, the young Lola Álvarez Bravo, Gertrude Duby Blum and her husband, the filmmaker Viktor Blum, converge with the German photographer Úrsula Bernath. (SEE) Bernath, born in Leipzig and trained in the wake of the Bauhaus, was briefly an apprentice in a photographic studio, but the destruction, the bombings, the lack of materials and her condition as a Jewish woman they made their practice impossible, emigrating to Mexico in 1946 as a widow with her three small children, where her parents had already taken refuge. As Bernath affirms, the new city imposed other rules: “I always… all my life wanted to be a photographer. But in Germany it was not possible to take pictures and sell them, it was necessary to be registered as a photographer. I couldn't exercise. When I arrived in Mexico I knew that here it was different. I didn't need to have a 'registration number.' Here, if it was a good photo, it was sold... if the photo was bad, it wasn't sold." (5) In 1967 she published her first photobook as a tribute to her adopted country, Mexico: the land, the art, and the people (co-edited with Richard Grossman under the Universe Books imprint).

In the Sudamerican archive it is possible to follow the footsteps of other photographers whose work still remains semi-hidden. The work of recovery and interpretation of the work of the photographer Hans Mann for the publications of the National Academy of Fine Arts is well known; (6) but within that corpus hides in plain sight that of Irene Brann (né Jacoby, born in Dresden), a photographer trained in Hamburg and London who emigrated to Bolivia with her husband Fritz Brann, who was employed as a mining engineer in Potosi.

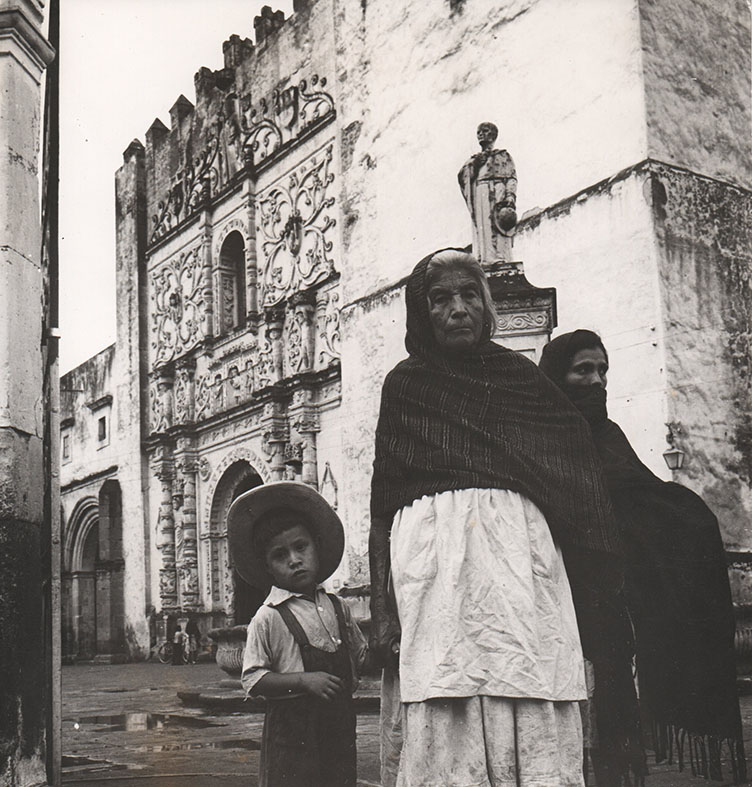

Irene Bran: Cathedral of Sucre. Bolivia. Circa 1944.

Brann developed a successful photographic studio in the city, at the same time that he witnessed the 1946 workers' and revolutionary uprising in Pulakayo. In 1953 her husband is transferred to Lima, Peru where Irene Brann enrolls in the newly founded Catholic Academy of Art and studies fine arts with the émigré painter Adolf Winternitz, also developing a career as a plastic artist.

Ilse Mayer: Puerto Iguazú in Alto Paraná. Misiones, Argentina, circa 1940.

Within the group of the now famous "Folder of the Ten," a group of professional modern photographers, almost all émigrés, were brought together, including Hans Mann himself, Anatole Saderman, George Friedman, Fred Schiffer, Max Jacoby, and whose female members were Annemarie Henrich, and more briefly, Ilse Mayer. (SEE) Ilse Mayer was born in Frankkfurt and trained at the Bayrische Staatslehran stalt für Photograhie in Munich, arriving in Montevideo, Uruguay in 1940 under circumstances similar to Freund and Mandello's trip. She initially found a job there for the tourist office, photographing the city, the beaches and coasts that became tourist attractions. In 1945 she moved to Buenos Aires and began an independent professional career, collaborating in the advertising agency of Walter Thompson, as well as correspondents for Argentine and international magazines, such as Vogue, Harper's Bazaar and Holiday. From 1946 she is an exclusive reporter for Time-Argentina in Buenos Aires, and she made trips that took her to the interior and also to neighboring countries. Mayer undertakes as Jeanne Mandello a return to Europe towards the end of the 1950s, but while she settles in the city of Barcelona with her new husband Lothar Bauer, Mayer settles in Ibiza and then returns to Frankfurt. Mayer's photographic work is today scattered in the archives of these magazines, and we do not know of a repository of her own. In 1969 his photobook Ibiza in Germany was published and several of his portraits of the German philosopher Theodor Adorno, with whom he met again when they both returned to Germany, make up his archive at the Institut für Sozialforschung, the headquarters of the well-known Frankfurt School, where Gisèle Freund herself had begun her university studies before going into exile in Paris.

Gisèle Freund: Puppets of San Carlino. Lady Caroline. Rev. Creative Freedom, No. 1. La Plata, Argentina. 1943. P. 179.

Perhaps the most evanescent figure of this group of photographers who passed through Argentina is Käte Weinzetl, who we know worked as a professional photographer in the country since the late 1930s, but later emigrated again to the United States. Following the research on the photographic work of Horacio Coppola and Greter Stern in the 1940s and early 1950s, I was able to see how their name crossed the photographic itineraries and the circle of émigré intellectuals that Coppola and Stern were part of. Photographs by Käte Weinzetl make up the 1937 Socialist Yearbook, where both photographers also participated at the same time in their own photography and advertising studio. The edition of the photobook La Plata to its founder, published in 1939 by the city municipality on the centenary of Dardo Rocha—the third urban survey project carried out by Coppola after his founding vision of Buenos Aires in 1936 and Historia de la calle Corrientes in 1937—was in charge of Coppola himself, who designed the cover and selected images. The section “La Plata 1939 by Horacio Coppola” contains 72 of his own images where he rehearses a vision similar to geometric frames, night frames and the contrasts between tradition and modernity that found his modern urban photographic vision. Other contemporary photographers are included in the section "Estampas Platenses" and Käte Weinzetl's images appear, which distances herself from the panoramic postcards of foundational buildings, to reveal a contemporary, modern daily life, close to the popular sectors, photographs entitled "Typical suburban street”, “Workers' neighborhood” “Workers' housing in Ensenada”. Finally, in 1943, the first issue of the magazine Libertad Creadora directed by Guillermo Korn and in which Coppola collaborated with his photographs of La Plata, Grete Stern with copies of lithographs, the artists Carybé and Clement Moreau with engravings and drawings, can be seen a photoreport by Weinzetl that accompanies Javier Villafañe's note on "The Puppets of San Carlino." Austere portraits of popular artists and close-up images of the puppets that reflect their liveliness and plastic expression.

Hilario. Artes Letras Oficios has been one of the places that I have been able to turn to as a researcher, since it recovers and re-circulates photographs of several of these artists and professionals, helping to counteract the oblivion, loss, silencing or erasure of this rich visual production. The history of modern photography in Argentina and Latin America continues to be written and its perspectives expand, and the compilation of forgotten works is the basis for future research.

Notes:

1. Lucia Moholy A Hundred Years of Photography, 1839-1939, Middlesex, England: Harmondsworth, 1939. (My translation).

2. See The New Woman Behind the Camera, Andrea Nelson, Mia Fineman, et al. National Gallery of Art, Washington, 2020.

3. Gisèle Freund, The World in my Camera, New York: The Dial Press, 1974. (My translation)

4. Interview of Emilio Cárdenas Elorduy with Kati Horna, May 1993, for the Documentary Series of the INBA Historical Archive, Kati and José Horna Private Archive of Photography and Graphics/Film Library of the UNAM.

5. Ivan Carrillo. “The documentary work of Úrsula Bernath. Reflection on her photographic archive”, Revista de la Universidad de México, No. 588-589, 2000, pp. 48-56.

6. Hans Mann: views on cultural heritage, Patricia Méndez, Mariana Giordano, Adela Gauna, et al, Buenos Aires, ANBA -CEDODAL, 2004.