On more than one occasion I have referred to the work of Josefina Plá as a crossroads event, which is clearly visualised through a tour of her life and work.

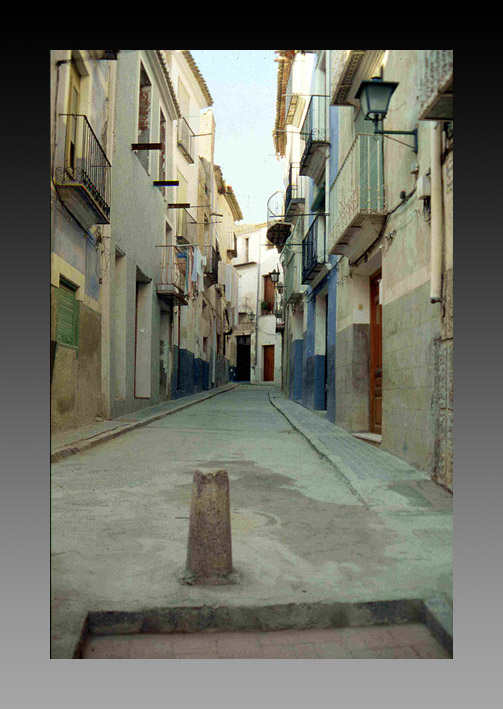

In Villajoyosa, one day in the summer of 1924, Josefina Plá and Andrés Campos Cervera (better known by the pseudonym Julián de la Herrería) meet at the house of Mimí, the Paraguayan artist's niece. Chance (another name for destiny, Borges might say) brought them together in that small but beautiful Alicante town on the Costa Blanca, in whose old town the house where young Josefina lived with her family is still preserved.

Thus began a love affair that would last until Andrés' death, thirteen years later, in 1937. During that time, Josefina collaborated closely with her husband in the field of ceramics, while at the same time devoting herself to her first vocation: poetry, and later theatre, narration, essays and criticism. They had married by proxy at the end of 1925, and in February of the following year the man who would become one of the greatest figures of Paraguayan culture in the 20th century set foot on Paraguayan soil.

Josefina Plá never returned to Villajoyosa. In 1993 I wanted to know the place where her Paraguayan and Hispanic American destiny had been tied together. There, in the company of Alicia Campos Cervera, my wife and I walked through the narrow and sometimes steep streets of the old town. Going down Calle del Pozo, and then Calle de la Escalereta, you reach Portalet, almost at the edge of the sea. The Escalereta and Portalet would serve as motifs for more than one engraving by Julián de la Herrería: Josefina remembers this event in the biography she dedicated to her husband. On my return, I visited my elderly teacher and showed her the photographs I had taken in Villajoyosa. When she saw one of them, she told me, shaken by emotion and with a broken voice, that one of the balconies on Calle del Pozo was that of her old house. Perhaps it was the last time she saw an image of the city where she had lived part of her youth and had met the man who would become her teacher and companion.

Julián de la Herrería, El Portalet Villajoyosa. Heliogravure, 1923. Reproduction of this image is prohibited without the express permission of the author.

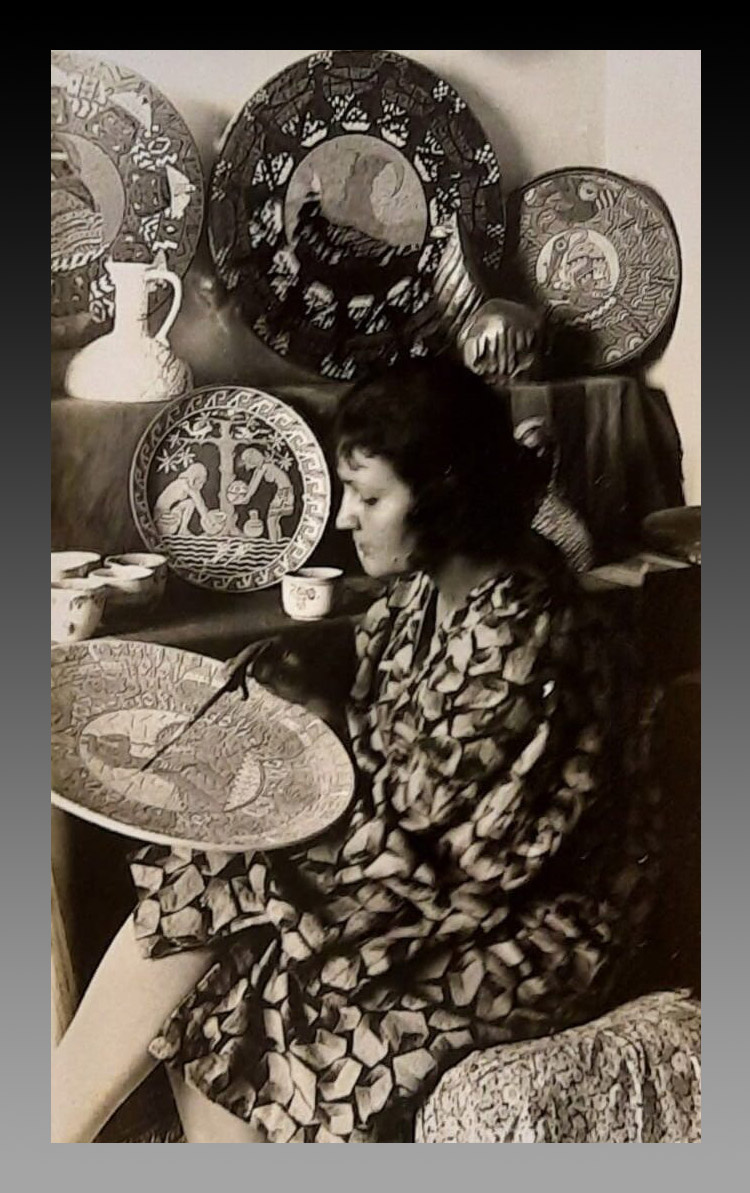

Her marriage to Julián de la Herrería lasted only thirteen years. These were decisive years during which she came into contact with Paraguayan reality and with the art of the great indigenous American civilizations, which would be the thematic focus of much of Julián de la Herrería's work and of her own. With him she also discovered the popular scenes of the gourds sgraffito by the Indian Catalina. This would lead to a large series of ceramics by the Paraguayan artist, in the last stage of his life. For Josefina Plá it was the starting point of what years later, in her maturity, would be the theme of her ceramics with popular Paraguayan and indigenous themes of the extinct Payaguá ethnic group.

But she also learned the technique of engraving, in particular that of woodcut, with Julián de la Herrería. If he was the first modern artist in Paraguay, his wife would also be, in the 1920s, the first modern engraver, and later, a key figure in the artistic movement that, starting in 1954, with the Arte Nuevo group, established the avant-garde concepts and languages of 20th century art in Paraguay.

Her work in the field of ceramics was not only a continuation of the task of rescuing pre-Hispanic aesthetic values, as Julián de la Herrería proposed in part of his work, but also as an experience of modern forms and those of the American tradition. For this reason, her work is also a testimony of disjunctions and conjunctions, to the extent that the signs of one and the other semantic universe are excluded, combined or fused in her artistic work.

Left: Julián de la Herrería, Mamopa rejhó Josefa. Dry-string ceramics, 1936. Right: Josefina Plá, Malay motif. Dry rope with metallic reflection, 1936. Reproduction of these images is prohibited without the express authorization of the author.

Years later, in times of struggle for new artistic expressions, the work of Josefina Plá (in collaboration with her disciple José Laterza Parodi) was recognized at the IV São Paulo Biennial (1957) with the Arno Prize. Later, international distinctions would come for Edith Jiménez, Hermann Guggiari, Carlos Colombino and others. Both the work of Julián de la Herrería and that of Josefina Plá made ceramics a major art and today we can place them among the most notable of Paraguayan artistic production of the 20th century.

Owl Jar, a piece by Josefina Pla that is part of the Julián de la Herrería Museum Collection.

At the same time, Josefina Plá's creative work was developing in the field of letters. First of all, poetry: her production in this field is - I have no doubt - one of the most valuable achievements of modern lyric poetry in the Spanish language. It was initially produced when that extraordinary constellation made up of Delmira Agustini, Gabriela Mistral, Juana de Ibarbourou and Alfonsina Storni were already shining in the Spanish-American literary sky. Perhaps for this reason it has remained somewhat veiled in the eyes of critics. However, compared to her illustrious predecessors, Josefina Plá's poetic work is in no way inferior and often soars and breaks new ground due to the intensity and beauty of her expression, full of existential meaning.

Both exhibited their ceramic work in Madrid, at the Círculo de Bellas Artes, in 1931.

Her dedication to the theater was equally constant, to which she gave high-quality works such as Historia de un número and Fiesta en el río, pieces that are among the most important of contemporary Hispanic-American dramatic production.

In the second half of the 1950s, Josefina Plá published a series of short stories in the magazine Alcor, part of which she later included in the edition of La mano en la tierra, in 1963. By then, El pozo and La babosa, by Gabriel Casaccia, and El trueno entre las hojas and El baldío, by Augusto Roa Bastos, had already been published. Although Josefina Plá's short stories also focused on aspects of our world, her particular significant and expressive configurations were clearly distinguished from those of these writers. Josefina Plá's narrative world is situated at the intersection of the Hispanic semantic universes (original to the author) and that of Paraguayan and Hispanic American expression, which would ultimately be the pragmatic sphere of her speech and her style. In this way, her literature apprehends, combines and crystallizes in a literature of high aesthetic importance the signs of her original homeland and those of the land that in the final hour her hand would finally touch definitively, like that of the old Spanish nobleman in her story “The Hand in the Earth.”

On January 11, 1999, a blind and deaf old lady, born almost ninety-six years earlier in Lobos, a small island in the Canary Islands, who met the great love of her life in a charming village on the shores of the Mediterranean Sea and arrived in Paraguay on February 1, 1926 to the glory of her art and literature, died in the world, leaving behind as a legacy a work of extraordinary value for its vital authenticity and aesthetic plenitude.

* Special for Hilario. Arts Letters Trades