In 2009 and 2020, respectively, UNESCO included tango and chamamé on the representative list of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity. Two melodies, two poetic, two dances of different geographical origins that have in common two musical instruments of great similarity and origin that unites and distinguishes them, the bandoneon and the accordion -the former, derived from the latter-, and the characteristic and unique to each of their dances.

Tango and Chamamé have had a history and an evolution with codes that the dancers themselves discover and define only by dancing. Both are in a continuous dialogue with the traditional; however, the classic and the new collide. And that collision is precisely what makes them a Living Heritage!

Tango is a music, a dance and an urban expression, born in the Río de la Plata, and which today achieves worldwide renown. Chamamé, on the other hand, of rural origin, includes Guarani words in its lyrics, a language spoken by the first inhabitants of the Argentine coast, where it comes from. Of a popular nature, the chamamé is directly linked to the geography of the Mesopotamian region, the beauty and strength of its rivers, landscapes, animals, flowers, religious spirituality; everything is a living part of his music and his poetry that resounds while the dancers dance with their humble canvas shoes, on a dirt floor that raises the dust that is part of the dance itself.

On this occasion we will show two worlds, two music, two dances, with their representations and their rhythms, with their instruments and their incorporations, their classics and their future classics, to share with you the emotions and talent of their creators.

On September 30, 2009, Tango was declared Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity by UNESCO [1] based on a joint presentation by the Government of the Autonomous City of Buenos Aires (Argentina) and the Municipality of the City of Montevideo (Uruguay).

The event was received with great joy by many, but it is fair to mention that it also produced resentment regarding the possible uses that tango could be given and the "denaturalization" effects that it could entail.

Tango was born at the end of the 19th century in a context of consolidation of the national state and incorporation of the Argentine economy into the international market, accelerated urbanization and reception of strong waves of European immigration.

In the first decade of the 20th century it developed as a genre and in the following decade it was sung and a basic orchestral formation was formed. The dance became popular in Paris at the same time that -despite moral objections- it was accepted and spread throughout Buenos Aires society in a more domestic version that accompanies the musical transformations.

The bandoneon, of German origin, transforms the primitive high-pitched tango, agile and picaresque, and gives it that serious and melancholic timbre that becomes one of its most distinctive identity traits. The dance is also simplified, abandoning the spectacular acrobatics of the "cuts and breaks" and becomes an elegant ballroom dance "from head to toe", which contributes to its universalization.

Around 1917 the typical tango orchestra was consolidated, differentiating it from other genres. It is about the sextet made up of two violins, two bandoneons, piano and double bass... Very varied styles will evolve from these two tendencies: one is the border tango and the other is melodic in orientation (Frenchified) which frees it from its strong and sharp modality of milonguero affiliation. This melodic orientation will fork, in turn, into two important currents: solo instrumental tango and song tango.

Great musicians will emerge from the instrumental melodic line. The most emblematic is Astor Piazzolla, whose work between 1946 and 1955 is recognized by everyone, especially by young people.

Tango was, is, and will always be Carlos Gardel. Azucena Maizani. 1957. El Olmo Confectionery. March 21, 1957.

Despite its withdrawal, the tango continues to form part of the family celebrations or the neighborhood carnival, and takes refuge in specific halls -well differentiated from the youth discotheque- where they continued dancing while waiting for better times... In In the same decade of the 70s, the seduction of Piazzola's music was added to musical and poetic innovations: lyrics by authors such as Horacio Ferrer and Eladia Blazquez achieved greater acceptance among young people, but also became the target of criticism for part of the defenders of traditional tango.

A fact worth mentioning at that time was the success of the show Tango Argentino at the Chatelet Theater in Paris (1983) where a type of dance was shown, the milonguero, which could be practiced socially and by people of various conditions: "chubby" , “peeled”, “short”, “we were not 20 years old”, according to the words of a member of the Company (Maronese, 2008).

Since then, the practice of dancing has not ceased to increase both among Argentines and foreigners, reviving old milongas and opening new ones. Today, the tango space is multigenerational in the fullest sense of the word. In the "milongas" [2] participate from the very young to people who are over 80 years old. And although there are differentiated circuits in which one type of age predominates, in most there is a very heterogeneous mix.

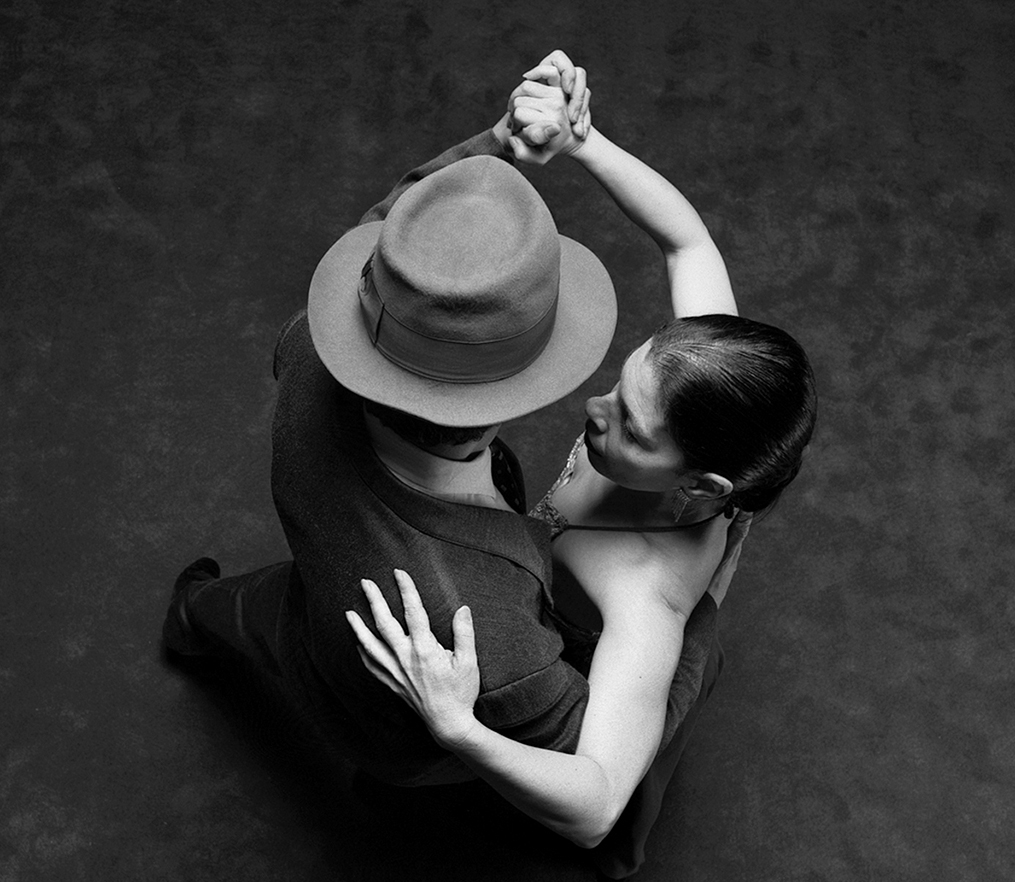

Tango in the city of Buenos Aires. Photography: Courtesy of Buenos Aires Tourism.

The first nomination of Tango as a Masterpiece of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity, carried out from the National Directorate of Heritage of the Ministry of Culture of the Nation in 2001, was unsuccessful.

It took another eight years for the second candidacy to be successful. Two factors contributed to this: the application strategy and the context of production of intangible heritage. Tango was nominated as a "River Plate expression", shared by the cities of Buenos Aires and Montevideo, and endorsed by both nations. And in 2003 the Convention for the Safeguarding of Intangible Cultural Heritage had been approved and ratified, in which the definition of Heritage was substantially enriched by incorporating the pluralistic concept of identities. This line of work continued to deepen after the declaration on Tango and in 2011, UNESCO experts extended the Intangible Cultural Heritage to the urban and contemporary dimension, while the idea of "authenticity" was replaced by " historical continuity” of the original expressions of a community.

We believe that safeguarding and innovation are not opposite, but rather complementary. Venturing into the great styles and techniques of the past is a step in learning and a cultural anchor, while creation and innovation is the continuation of that process of identity construction.

The priority today is joint and participatory work with those who create and recreate tango on a daily basis, giving it its vitality, since they are the ones who possess the knowledge, the experience and build its meaning and sense. In order to fulfill these purposes, we propose meeting instances with the different groups. Only through this participatory interaction will we be able to build an inventory that accounts for the variety of social subjects, their knowledge, practices, experiences and how they build the meanings that form the symbolic world of the multiple social spaces linked to tango, never exempt from tensions and disputes. . It is the State that must accompany their proposals and generate instruments that help them overcome obstacles, opening a common space to established and unknown protagonists, to large institutions and small centers, the internationally known and neighborhood ones, the traditional and the innovators.

Presentation of Chamamé at UNESCO

The chamamé is a cultural manifestation that is expressed through music, dance and poetry. Its name refers to the Guarani language that the inhabitants of the northeast of Argentina spoke when the conquerors arrived. However, no one speaks the original Guarani today. This language was transformed and even in historical times it was prohibited, but today it is the second language in the region. The Guarani that was spoken was a "lingua franca" used so that they could understand each other even with the Jesuit missionaries; they all learned it to be able to communicate in a territory so vast that it reached the line of Ecuador, until then inhabited by the Guarani.

The application began in the province of Corrientes, although in our territory there is a kind of chamamecera aquifer "nation" that has to do with all of Mesopotamia -I mean the provinces of Entre Ríos, Corrientes and Misiones surrounded by the Uruguay and Paraná-, and I express it because his music and his lyrics have a lot to do with the river, with the relationship of man with the river, with the worker and has to do especially with being; they say ñandereko in Guarani alluding to “the way of being” of all of them.

Although the epicenter of this manifestation is the province of Corrientes, the chamamé has spread to the south of Brazil, Paraguay, Uruguay, and I expressed it, in the other provinces of the coast, they speak of the "chamamecera nation" that is music , which is language and which is dance.

While the presentation to UNESCO was being prepared, a feeling around its own music and identity was revitalized in the province, driven by the meetings organized to think and reflect on chamamé and heritage.

Chamamecero patio in Santa Rosa, province of Corrientes. Photography: FM La Ruta, Santa Rosa.

They used to say in the workshops, “when we are very emotional we have to use a word in Guarani”, it is his mother tongue and they turn to it to express it.

Music totally disqualified by the local upper classes and very widespread here in Buenos Aires, because many people from Corrientes have had to come to this megacity in search of work. Women who clean houses, bricklayers, bar and restaurant waiters... always willing to create their community spaces as in any migration process and in each of them what they do is sing and dance chamamé, there are even many who remedy " the nostalgia” of not being in their land listening to chamamé.

As a safeguard and revitalization, the key is that the old and classic chamamés dialogue with the new writers and interpreters in order to obtain new creations, because that will be the way to keep heritage and cultural expression alive. In this sense, the role played by intergenerational transmission in the practicing community is important. The identification of artists belonging to the second or third generation of chamamé musicians and dancers within the same family is recurrent.

We indicated it above, another element mentioned repeatedly by the carrier and practicing community during the consultation process is the "Ñande Reko", an expression in the Guaraní language that means "Way of being and being".

The chamamé constitutes the livelihood of those wearers and practitioners who dedicate themselves professionally to providing musical performances, teaching dances, designing costumes, embroidering blouses, and manufacturing and repairing musical instruments. In addition, within the academic space, the Free Chair "Chamamé Raity" Nido del Chamamé was formed at the National University of the Northeast.

Both expressions are enriched with new creations and are protected in this way. And its inscription on the UNESCO list, we understand, will contribute to the strengthening and visibility of those other cultural expressions related to popular music, song and dance that are not yet incorporated into the Representative List.

Notes:

1. Within the framework of the Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage, approved by UNESCO in 2003.

2. “Milonga” is a specific type of music and dance. It is also used to name the spaces where people gather to practice the dance of tango (and milonga).

* Special for Hilario. Arts Letters Trades