Grandfather Ignacio Fotheringham, Roca's lieutenant during the Conquest of the Desert, had come to the country from Southampton on the recommendation of his Argentine neighbors Juan Manuel and Manuelita Rosas. Married to Adela Ana Ordoñez from Cordoba, he settled in Río Cuarto. One of his daughters, Maria Isabel, married the lawyer and judge Benjamín Castellano, with whom she had two boys and two girls. Until the arrival of Maria, the youngest of the four siblings, Mabel was her father's favorite. So much so that when grandmother Adela, president of the charitable ladies, organized a raffle for a celluloid doll at the Municipal Theater, Benjamín Castellano bought 10 numbers so that his daughter would have a better chance.

On the day of the event, Mabel went with the expected anxiety, praying that her grandmother would pick one of her numbers from the lottery. 12! The 12th was hers! She jumped up from her seat as if on a spring and ran towards the stage shouting: Grandma, it's mine! It was then that Mabel received her first lesson in civic honesty: "No, my child, you can't win, it's my granddaughter and you yourself are going to give the doll to the new winner." And the little girl remained next to her grandmother, as if glued to the stage, with her eyes filled with tears and her fists clenched, watching another little girl take her treasure and she swore to herself that "one day, when I grew up, I would have enough dolls to fill an entire house and much more."

At the end of the 1940s, when Benjamín Castellano died, the economic situation forced his wife María Isabel Fotheringham to seek the help of her older sisters, leaving with her daughters for Buenos Aires. There she began her brilliant career as a ceramist, giving volume to the most representative paintings of national art. Mabel helped in her own way, getting up at dawn to take two buses to the provinces, where she taught drawing classes at a state school. María, still a teenager, typed boring commercial phrases in an office near Galerías Pacífico. At lunchtime, she sought solace in the windows of antique dealers.

One pay day, with her salary in her purse, María entered the Larco store. On a shelf, almost invisible among so much stuff, there were two French dolls, with their moist sulfur eyes and scratches that she could surely repair herself. And she didn't hesitate. She asked the price and was embarrassed to say that it was almost all of her salary... Besides, taking one and leaving the other was not even a possible option. María emptied her purse and left Larco with the dolls wrapped in newspaper.

In the room she shared with her sister Mabel, she hid the package on top of the wardrobe, behind the hat boxes. While her friends were spending money on silk stockings or sighing over Frank Sinatra records, Maria had just burned her salary on two porcelain dolls.

- What's happening to you that you're so quiet? - said Mabel, who knew her silences very well. She followed her to the room, saw her stand on a chair, take down a package from the wardrobe and open it with the delicacy of discovering an unfathomable mystery.

- How much did this cost you? It must have been a lot!

- Aren't they pretty? They need someone to repair their little dresses and you know how to sew.

Mabel ran her fingers along the loose pleats of the dress and raising the doll to her chest said: I have the ideal lace for this hem.

Could we say that it was in that moment of complicity that everything began? It is probable, but what certainly happened was that they decided that what they were going to undertake could only be done together. In a first step, they acquired specialized bibliography to study and gather the greatest knowledge about that collectible object.

Mabel and Maria focused on France and Germany. There were no better dolls than those produced by these two countries from the second half of the 19th century. The Bavarian porcelain factory belt in southeastern Germany, the "white gold" route, was the first porcelain to be made in Europe. And if Germany had its Meissen, France had its Limoges. However, with Paris being the center of fashion, it was difficult for the Germans to compete with French clothing design. All the innovations in the doll industry that we know today were created by these two powers between 1850 and 1914, and the Castellano Fotheringham sisters tried to find each one of them.

The collection was set in the midst of the change in industrial leadership from Franco-German to the United States and Japan at the end of the Second World War. On the one hand, the shortage of materials in the face of the priority given to arms and, on the other, the persecution of the Jews [a good proportion of the manufacturers were Jews] were the causes of the decline of France and Germany as toy powers. And although American production never had the quality of European production, the most celebrated American example was the Shirley Temple. The "silver screen" made this doll of the little film star flood the toy shops of the world in various sizes.

In our country, the most sold Argentine toy was no less important: Marilú. The Castellano sisters did not ignore this famous doll, but, initially, they limited themselves to collecting those that Alicia Larguía, its creator, ordered to be made in the German factories of Kämer & Reihardt and, later, König & Wernicke, which, like so many other firms, was brought to a close by the war.

The great originality of Marilú was the perfect combination between the German doll and the clothes and fashion accessories produced by the tailoring workshop of the Argentine firm. When shipments stopped in 1939, Larguía took on local production with Bebilandia. After many years of having started the collection, Mabel and María understood that it was necessary to complete the circle with the national Marilú.

In the spring of 1954, the Castellanos dared to break into the strictly male sphere of antique dealers and gallery owners, to found, together with Ivonne Fauvety, Nelly Freire and Elena Patrón Costa, the Antigona gallery. It was a basement of the old Hotel Príncipe de Gales, opposite the Catalinas, and yet, within a decade, it became the obligatory meeting place and, in many cases, the starting point of the artistic career of countless young talents. They were the first female gallery owners and decidedly innovative in exhibition areas that, only later, the great museums would take up, such as generating dialogues between historical heritage and contemporary art. Thus, their antique dolls appeared for the first time on the public scene.

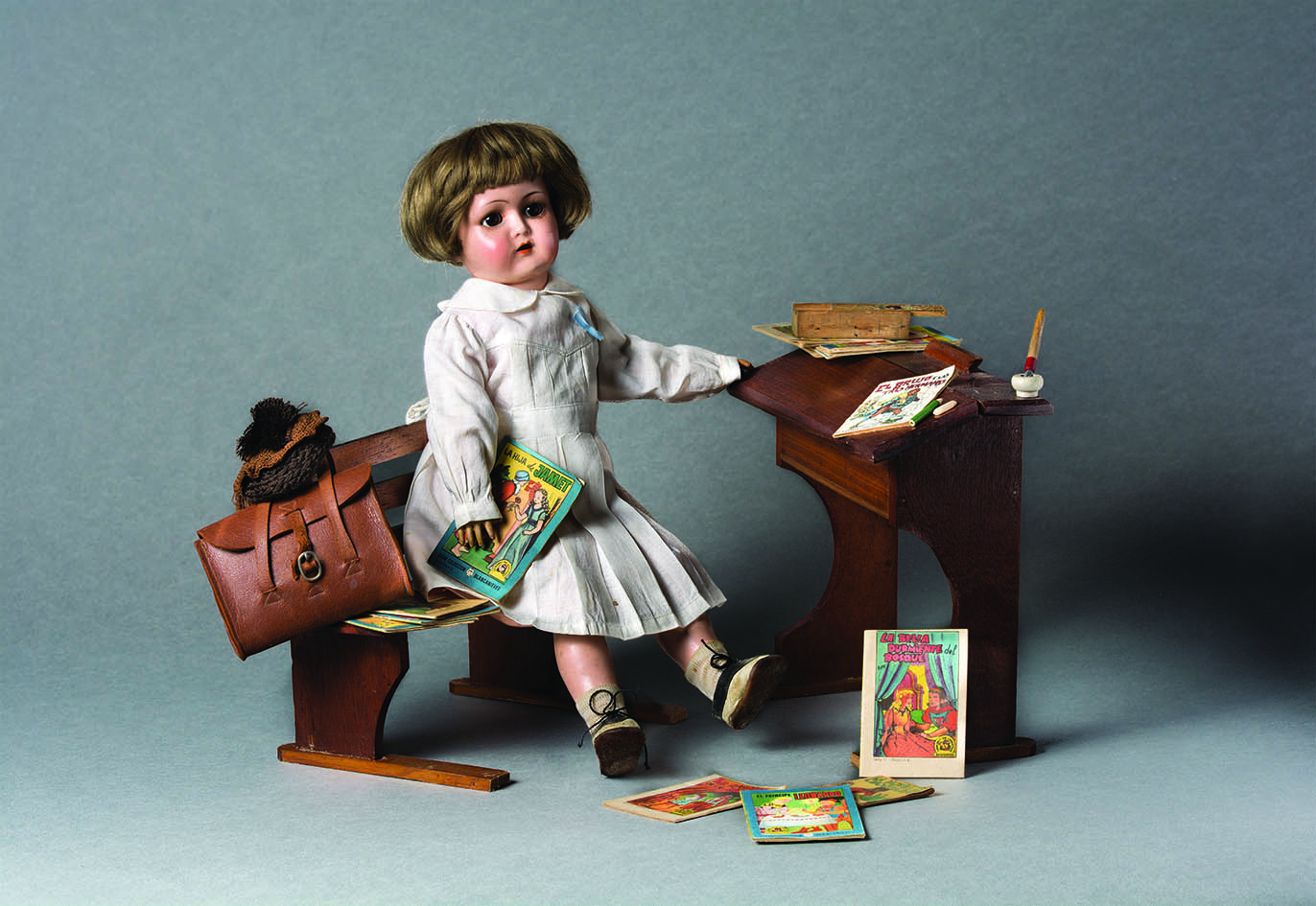

In the eighties, several examples of Jumeau bébés, the best French dolls, participated in an exhibition of antique toys held at the Fernández Blanco Museum. Since then, Mabel and María forged an indissoluble bond with that institution. First there was Barro y fuego, an exhibition on her mother's ceramics that led to the donation of a 14-piece Nativity scene in 1994. Four years later, they made a new and important donation, this time of paintings, images, furniture and colonial silverware. In 2003, they made public their intention to donate the doll collection with a memorable exhibition that still today has the largest number of visitors at the Palacio Noel headquarters.

Partial view of the exhibition "Once upon a time..." with the small works of art by "Las Castellanos". Fernández Blanco Museum. Photography: Mariana Cullen.

In 2000, the Fernández Blanco House, the original headquarters of the museum, had been recovered and it was decided to restore it to exhibit the collections of applied arts from the 19th and early 20th centuries. The Castellanos were the main promoters of this project and their donation of dolls for this new headquarters was the greatest boost. Once Upon a Time… opened in 2012, and for a long time the House was known as the “museum of dolls”. Three years later, the book-catalogue was published, entirely produced by the museum’s technical teams.

Maria inherited her profession as a ceramist from her mother and contributed a half-round sculpture of the Child Jesus the Good Shepherd to the façade of the chapel of the Noel Palace. She started from this plan first and when a centenarian Mabel also left us, the last batch of colonial art pieces was bequeathed by her nephews. Mabel and Maria already occupy a well-deserved place of privilege among the museum's benefactors, but its doll rooms will always be a timeless space, where these two girls will continue to play indefinitely.

* Special for Hilario. Arts Letters Trades