Every month, every week, I receive the programs from the movie theaters or concert halls that I once visited and signed up for, from anywhere in the world, to be aware of the dimension of what is happening in those times. parallels. Thus, a few days ago, the Krokodil cinema in Berlin announced that on Tuesday, May 7, it would commemorate the centenary of the birth of the Soviet filmmaker, Sergei Paradzhanov or Sarkis Howsepi Paradschanian (in Russian, Сергей Иосифович Параджанов), a son of Armenians, born in Tbilisi, the capital of Georgia, on January 9, 1924. And he would do it with an altar in the lobby and with the projection of, on the one hand, The Color of Pomegranates, his film from 1969, and, on the other, of Requiem, an interview conducted in Munich by the American Ron Holloway in 1988, when no one suspected that the filmmaker would die two years later. Also available on the internet, Requiem is a cinematographic essay, with photographs and fragments of his films, canceled or unfinished works and those made in the 1950s and 1960s, a set that Paradzánov would renounce by abandoning the parameters of the socialist realism.

The Krokodil program noted "In Soviet times, the Armenian director Sergei Parajanov was an 'enfant terrible' of Eastern European cinema. The visual intensity of his films and his collages - which deal primarily with the peoples of the Caucasus - delighted critics and film buffs around the world while being disapproved of by the Soviet leadership. The censors not only rejected his scripts: he was banned from working and he was imprisoned from 1974 to 1978 for propagating homosexuality.

From Ranelagh, next to a convalescent mother, we prepared to accompany or, rather, to discover from home this universe that my mother described as the strangest thing she had seen in her almost 90 years of going to the cinema. He was somewhat right: that same rarity has led Paradzánov to be considered today as one of the most original filmmakers of the last century. Not only that: this rarity also arises from the filmmaker's absence from the circuits of what some essayists have called "the cinephile left" of Buenos Aires, that is, that countless audience that, between the 1960s and 1980s, circulated [ We circulated, I should write] between the Cosmos 70, the Sala 1, the Hebraica, the Lugones and the Arte cinema, from cycle to cycle, from director to director.

"Only once" - said the advertisements that the newspapers published at least once a year - "Comprehensive Eisenstein." And there at the Cosmos, we met to see the films distributed by the hammer and sickle of Artkino, some acquired thanks to subsidies from the Soviet embassy in Argentina and others through the Czechoslovak office. Two aesthetics where the psychedelia and experimentation of the second contrasted with the pomp of War and Peace (1966-1967) by S. Bondarchuk, premiered in June 1969 in the theater on Corrientes Street, in which – according to the studio by Valeria Galván and Michal Zourek - remained on the bill for 28 weeks, attracting almost 160 thousand spectators. Among them, my family. My paternal grandfather, they say, was shocked while, in the Transcaucasian countries - those that my grandfather also adored - Paradzhanov ranted about the number of horses that Bondarchuk had obtained for his productions while he even had his sheep taken away. And not to mention the flame.

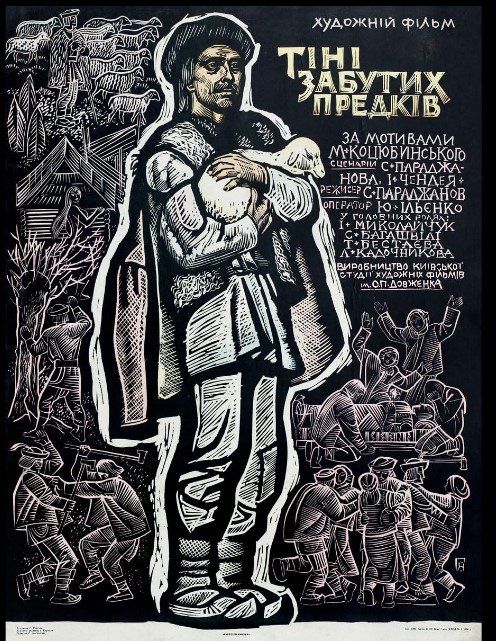

In the Cosmos, the Soviet border passed through Tarkovsky, friend and source of inspiration of Paradzánov or Parajanov, according to the English transliteration. He had studied at the Moscow Film Academy and worked as a director in Ukraine. His style and visual arts - the term he used to describe his films - earned him international recognition and allowed him to obtain several awards, such as the prizes won at the 1965 Mar del Plata Film Festival, where "The Shadow of Our Forgotten Ancestors" » or «Steeds of Fire» – in addition to being nominated for best film – won the special jury prize and the critics' grand prize. Despite having arrived in Argentina with the help of the Soviet delegation, Paradzánov does not seem to have obtained a place in the Buenos Aires Cosmos and, therefore, not in any country on the continent since Artkino Argentina was the entrance to European cinema. from the East to the rooms of Ibero-America. Battleship Potemkin, yes, kyiv Frescoes, no.

It is not surprising in a country that, as we know, knew how to maintain good relations with the USSR: in 1974, Paradzhanov, after years of espionage, was sentenced to five years in prison on fabricated charges that included sodomy, homosexuality, his alleged activities in the black market and trafficking in works of art. When he was released, partly due to the interference of L. Aragon and John Updike, he was prohibited from filming again and, when he did so at the time of Perestroika, Cosmos 70 was already in the doldrums.

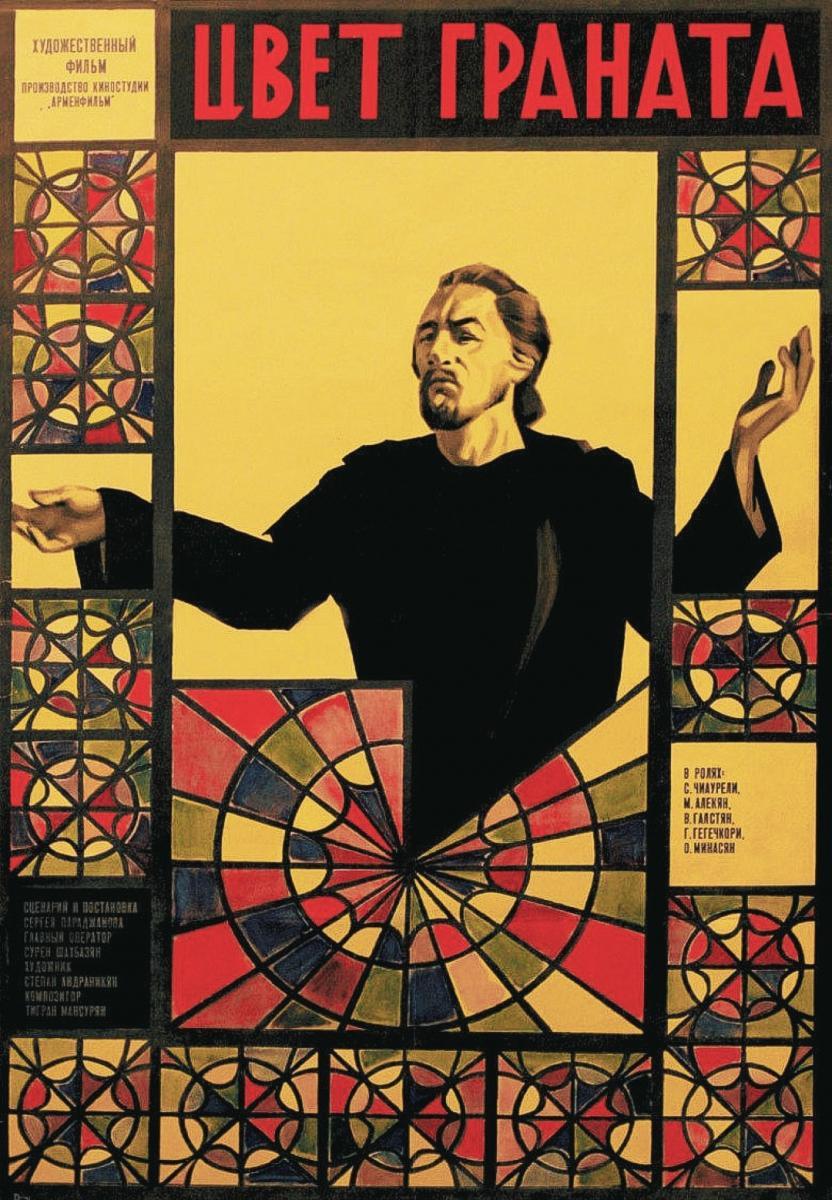

Paradzhanov's films of the 1960s caused a stir and annoyed not so much the rulers but the bureaucrats of the Moscow-based film industry. The file that finally authorized the filming, release and distribution of "The Color of Pomegranates" in 1969 has almost 200 pages. Starting with “Sayat Nova”, the original title that they considered misleading: it was a film dedicated to the poet Harutyun Sayatyan, the master of songs, who in the 18th century worked at the court of King Heraclius II of Georgia and who, after After the death of the king, he toured the country as a traveling bard until he was murdered and martyred. For the Soviets, he was an exemplary figure to promote transcaucasian and multicultural identity, since his compositions, in the form of traditional Armenian songs, were written in this language, but also in Georgian and Persian, using the Georgian alphabet and in a secular tone.

Paradzhanov's film – although it shows how people enter and leave languages and religions – is nothing like a biography like the one expected in Moscow. On the contrary: it is more like an art gallery, a museum of ethnography or one of natural history, a route that, far from proposing continuity, is made up of fragments, objects, paintings, isolated from each other by frames, frames, tapestries or walls. Paradzhanov, after all, was the son of an antique dealer, and he was a collector, a lover of collage. His cinema, in fact, is that.

The Color of Pomegranates is thus made up of several chapters that describe the stages of the troubadour's life through paintings or miniatures full of symbols, figures, animals, things, whose connection must be made by whoever looks at them. Little is said, most of the words are found in the titles that were added between one miniature and another, as a teaching resource and condition for its premiere.

Not only that: his films are a mockery of the ethnographies and folklore of the 19th and 20th centuries. Like Pasolini's Medea, they seem like a portrait of the archaic worlds of the Transcaucasian republics but, as the Armenian anthropologist Levon Abrahamian has highlighted, it is another composition that, as in museums, appeals to objects, costumes, decorations, rituals. and traditions that are supposedly ancient but that, in reality, are another invention of the director, the collector, the curator of the exhibition. An archaic modernity, as we agreed with Ghassan Salhab.

Paradzánov's characters change their religion and allegiances. Patriotic sacrifices – like that of the Suram Fortress – are orchestrated by amorous revenge and not by the design of the gods or the people. An unheroic world, like the one in which those artists had to live who bowed down to obtain financing or for their films to be distributed throughout the Union and beyond it.

Paradzhanov, while he was able to film, did so thanks to the support and admiration of several colleagues, professors and film directors of the republics in which he lived and filmed. Thanks to this, he managed to tighten the rope to the maximum, requesting more than Bondarchuk's horses. Many of the objects he used in his films were “real,” they came from museums or historic churches and, with the permission of state film agencies, were moved to the sets where they were filmed.

Among the many liberties that were taken - such as the abundance of religious symbols and scenes in a cinema that programmatically avoided them - the presence of flames in the Haghbat monastery where the poet Sayat-Nova lives and in other films by he. Flames in the mountains of Armenia, a wink to remind – in the attentive eyes of the seasoned zoologist – how far from realism his cinema is. Abrahamian suggests that, perhaps to naturalize the unexpected appearance of this animal, a scene where the monks milked a llama was filmed and was removed from the final version. But even in this case, one might think that he was making fun of everything: the llama in question was a male, which had been preferred because of his imposing body and because the female at the Yerevan Zoo was somewhat capricious.

Paradzhanov suggested that this animal, between a camel and a sheep, more than a source of milk, served as a partner for the monks. And along those lines, while the scenes were being filmed in the monastery, he decorated the wall of the hotel where he was staying with a drawing of his that scandalized the journalists and admirers who visited his room: an illustration of what they did to the flames in the mountains. Andean mountains, accompanied by the following caption: "And the shepherds, tenderly, kissed the llama on the lips."

In fact, Abrahamian continues, the flame episode brings us to one of the most interesting aspects of Paradzhanov, who often began a scene based on something unusual, absurd, provocative, to allow this hidden core to expand and darken with details. diluting the origins of the episode. This, transformed, acquired a resonance that no longer had anything in common with the previous, more earthly layer of meaning. Since in The Color of Pomegranates there is almost no camera movement, the articulation between the frames occurs through these displacements.

Paradzánov insisted and insisted to obtain the male llama, an animal foreign to the historical context of the film, which not only made it difficult to find but also to justify to those who had to sign the authorizations. When the flame arrived at the filming set, after tremendous difficulties and efforts, Paradzánov radiated happiness... With that satisfaction, he created one of the episodes of the film that would later lead to others, showing that flames like peacocks, Fish and pomegranates were part of this Old World created in the 20th Century.

In fact, think those who studied Moscow's secret archives, this insistence was very much in keeping with his compulsion to test the limits of what he could do, both in terms of film censorship and the social mores imposed by the morality of the game. By the way, in those years the ethnocentric hypothesis circulated on both sides of the ocean, on both sides of the Caucasus, that syphilis came from llamas, natural carriers of the disease, which passed from the Andean shepherds who took care of them to the women of the area, who in turn transmitted it to the first European explorers, through whom it reached Europe. A world where everything moves, where life and death have no flag but share, instead, the color of the pomegranate.

* Special for Hilario. Arts Letters Trades